Commentary: How bipolar disorder took my father's personality away

Let's begin with first definitions.

What is a "disorder"? From a quick Google search, it is disarray, confusion, a breach of peace, a disturbance or disruption of the normal.

Bipolar disorder is the beast living in my father's mind. It cannot be banished. It is shackled and put to a light sleep by Quetiapine and sodium valproate.

Unfortunately, there is no way to subdue the beast without subduing its host. On medication, my charming, intelligent father becomes a reserved man who smiles placidly and hardly speaks.

But there is peace and some sense of normality.

Last year, the beast broke free.

My father sensed the breach inside his mind and alerted us. He was sleeping less and talking more.

We tried to wrestle back control with more medication, by taking him into our home, but by the end of the week, he was letting the pills fall out of his mouth and oscillating between belting Teresa Teng songs jubilantly and crying woefully at 1am, threatening to jump off my balcony. He was experiencing a full-blown manic episode.

The week concluded with a distressing visit to the emergency department of the Institute of Mental Health (IMH) and the subsequent detention of my father for a month under the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) Act — an Act to provide for the admission, detention, care and treatment of mentally disordered persons in designated psychiatric institutions.

At the IMH, there was no negotiation with the beast. Six sessions of electroconvulsive therapy and a quadrupling of my father's usual dose of medication knocked the beast out good and proper.

It is not “treatment” when someone has to continue living under a haze. It is simply an enforced peace and order.

MAN OF MYSTERY

I still think a lot about that week when my father stayed with us.

The feelings are bittersweet. You see, when the beast broke free, so did my father's old personality.

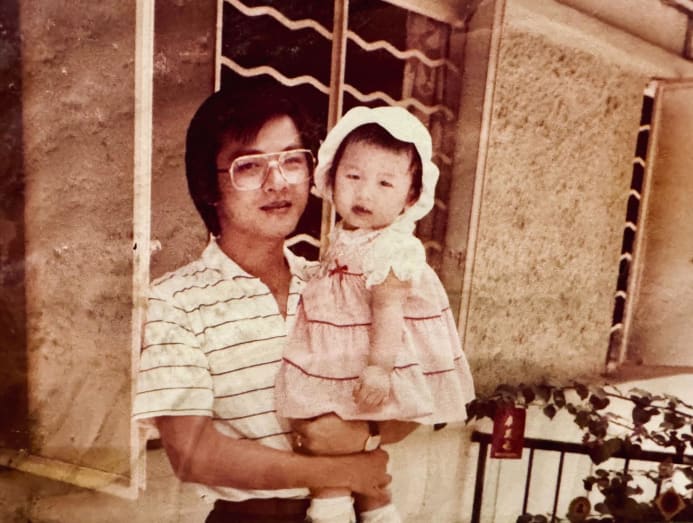

Growing up, I would joke, snidely as a teenager would, that my father was an international man of mystery. He travelled most of the week and was hardly present. I barely knew him.

Ironically, it was his bipolar disorder diagnosis that got him deported years ago and brought him home. He was broken and muted when we got him back.

In the early part of that fateful week, just before the mania took complete control of my father's mind, we saw a lucidity in him that we had not seen in a very long time.

His old personality resurfaced, as did his memories. He was smart and funny. He regaled my bewildered but amused children — and me! — with stories of himself as a child in Sibu, Sarawak, hungry for education and adventure beyond.

My father was one out of nine siblings and was expected to work in the plantation fields, not study.

At 17, my father heard that there was a Singaporean businessman visiting town and boldly asked him to take him to Singapore. That businessman was my late grandfather — my mother's father.

My maternal grandfather got my father a place at Ngee Ann Polytechnic, but my father wanted to work as well so he could earn his keep. He slept on the top floor of my grandfather's shophouse office, where the delivery man also stayed.

Obviously, my parents met then. My father said my mother played the piano beautifully and she would bring him food because he was so impoverished. When my grandfather was stricken with cancer, my father was by his hospital bed every day, massaging his bloated feet.

A BRIEF GLIMPSE

My father was never emotionally expressive, but that week, he told my mother and me deep regrets and feelings that he had kept buried for years.

In the long and stressful car ride to the IMH, we tried to distract my father with random conversation about football. But there was only so much enthusiasm that could buoy a conversation about Liverpool and Kevin Keegan as we drove from the East to the Northeast of Singapore.

And as we got to Buangkok, my husband burst out, “How did you fall in love with Ma?”

My father responded excitedly, “It was at her 21st birthday (party). I was so happy to be invited. You know we have the same birthday, just that I am a year older? So I got to blow out the candles with her.”

Just then, the car turned into the IMH compound. My father looked around at the strange surroundings and asked frantically where we had taken him.

“Please finish the story, Pa! I really want to know how you fell in love with Ma”, I pleaded. But it was too late.

When my father was at the IMH, I asked the doctors if there was a way to get his personality back while keeping the beast under control.

Unfortunately, the chemical balance in his mind is too delicate for risks.

My father is no longer detained by the IMH — but the detention of his personality under Quetiapine has to continue for his own safety.

For now, I shall be grateful for the glimpse of my father that I caught that week.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Joelle Yang is a lawyer and a mother of three. This piece first appeared in The Birthday Book: Unmasking, a collection of 58 essays on the new individual and collective possibilities for Singapore as we emerge from the throes of Covid-19.