Project Wolbachia: 300 million mosquitoes released but not a silver bullet to deal with dengue, says NEA

In areas with many mosquitos, the Wolbachia mosquitos cannot compete with them and will be “overwhelmed”, says the National Environment Agency.

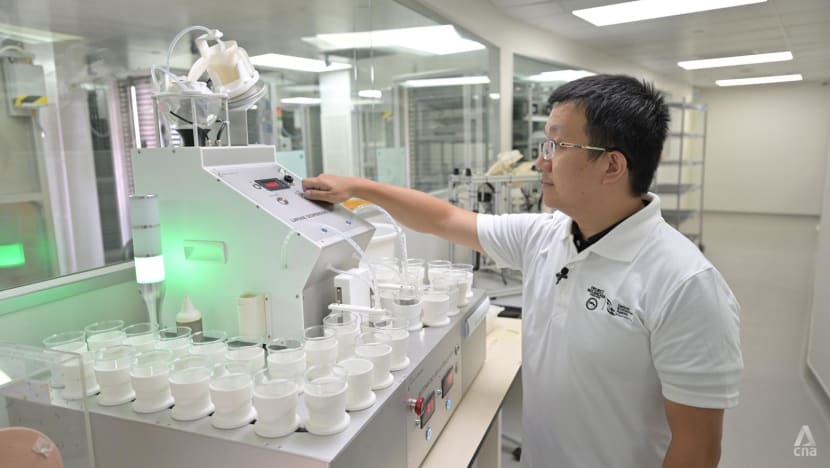

NEA senior scientist Deng Lu points at containers that hold strips where mosquitoes land to lay eggs. (Photo: CNA/Raydza Rahman)

SINGAPORE: A nondescript industrial building in Ang Mo Kio houses a lab that has bred more than 300 million mosquitos and is producing another 7 million every week.

This is the headquarters of Project Wolbachia, which produces and releases non-biting male Aedes aegypti mosquitoes at selected locations to mate with their female counterparts.

Because the male mosquitos carry the Wolbachia bacteria, the resultant eggs do not hatch and this helps to suppress the mosquito population.

Still, dengue cases in Singapore do not appear to have fallen since Project Wolbachia's launch in 2016. A total of 32,173 dengue cases were reported in 2022, the second-highest in a year, with the record high being 35,266 in 2020.

Earlier this month, the National Environment Agency (NEA) warned that Singapore is again at risk of a surge in dengue cases. Weekly dengue cases have hit several hundred and more than 50 active clusters have emerged.

Project Wolbachia is “not a silver bullet” to stem dengue transmission, said Dr Ng Lee Ching, group director of NEA’s Environmental Health Institute.

"Even with Project Wolbachia … it doesn't mean that you have no risk."

At several Project Wolbachia sites such as Tampines, Yishun and Choa Chu Kang, the Aedes aegypti mosquito population has fallen by up to 98 per cent and dengue cases by up to 88 per cent, said Senior Parliamentary Secretary Baey Yam Ken at a parliament sitting in March.

But while the Wolbachia technology is effective in reducing the risk of dengue transmission, it has to be complemented by dengue control efforts, said Dr Ng.

“If there are lots of mosquitoes out there, the Wolbachia that we send out cannot compete with them. They will be overwhelmed.”

The Wolbachia mosquitoes will thus be more effective in reducing the mosquito population if the wild types are brought down, she added.

The recent dengue spike has also been spurred by an increase in dengue virus serotype 1 (DENV-1) cases. This strain has replaced the previously dominant DENV-3 serotype.

“WE DON’T KNOW EVERYTHING YET”

Project Wolbachia now covers about 352,000 households, which is about 25 per cent of all households in Singapore, said Dr Ng. This is more than double the 160,000 households covered in the middle of last year.

“This is made possible because of the technologies that we have developed in-house to be able to produce more mosquitoes efficiently,” she added.

However, Dr Ng highlighted that Wolbachia technology is still new.

“They're still evolving, they're still improving. And that means that the process and the gadgets do have a lot of potential for improvement.”

Inside NEA's mosquito production facility

How are male Wolbachia-Aedes aegypti mosquitoes produced? NEA scientist Deng Lu shows CNA how it's done.

Step 1: Egg production

Mosquito eggs are produced in the adult insectary room, and these eggs are used for subsequent male Wolbachia mosquito production.

The room has several mosquito cages, each containing both male and female mosquitoes. At the bottom of the cage are ovipots or egg collection containers that hold several egg strips and stagnant water.

Mosquitoes like the rough texture of the strips and will land on them to lay eggs, said Mr Deng Lu, senior scientist and head of the mosquito production branch.

Step 2: Hatching eggs and counting larvae

A fresh batch of Wolbachia-carrying Aedes mosquito eggs hatch and become larvae within a few hours. They then have to be counted.

There are no turnkey solutions for mosquito production, especially for counting larvae, said Mr Deng. Initially, the team used telecounters and droppers – counting the larvae one by one.

Obviously, the process was not sustainable.

So the team developed its own counting machine, which can count 26,000 larvae in three to five minutes.

Step 3: Seeding the eggs

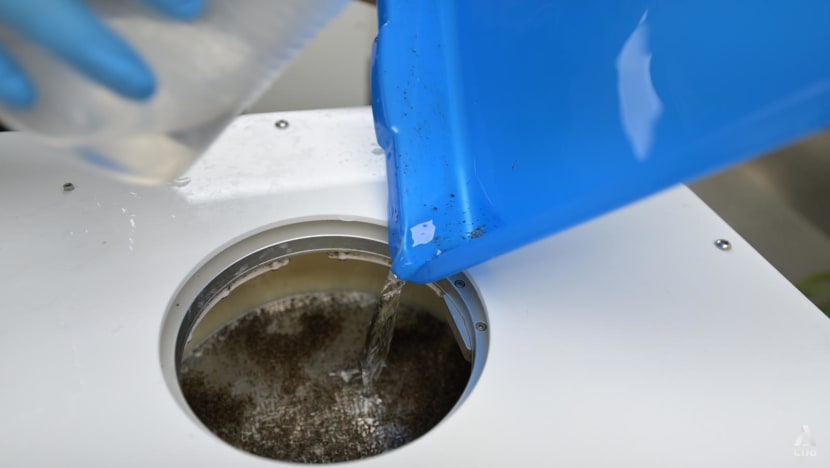

The next step is the seeding process. Each batch of 26,000 larvae is poured through seeding pods and channelled into individual trays. The trays are then loaded into a high-density rearing rack system.

The environment here has been designed for the comfort of mosquito larvae, with controlled humidity, temperature and airflow.

The team is “very precise” at every step, from mosquito counting and the strict feeding regime to temperature control, said Mr Deng. This is done to achieve optimal mosquito growth in terms of size and quality of yield, he added.

For instance, if there is too much food, the tray containing mosquito larvae will crash. If there is not enough food, the female mosquitoes will be smaller, making it hard to differentiate between the males and the females.

The mosquito larvae stay in the room for about seven days. On day seven, they are harvested for the next process – sex separation.

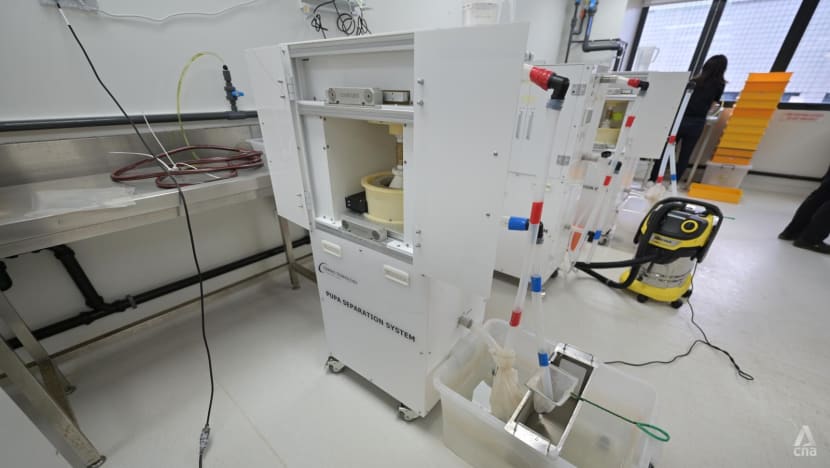

Step 4: Separating the males from females

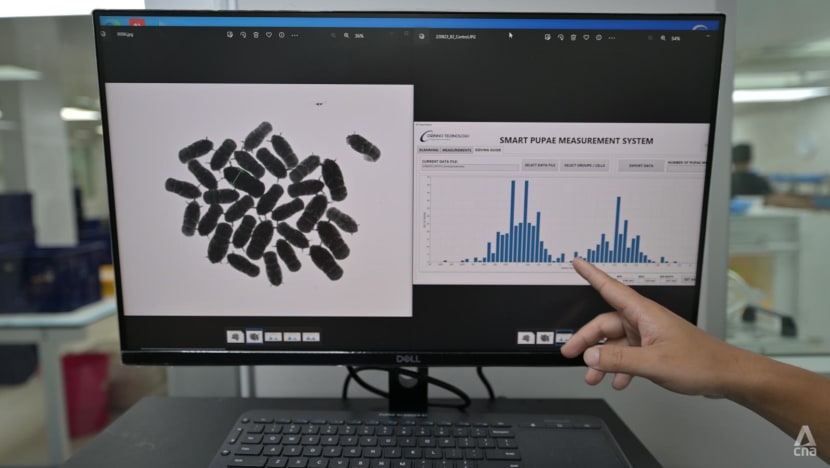

After the harvest, the pupae are analysed based on their size to separate the males from the females. This is done using an AI-based scanner which takes a picture of the sample pupae.

The scanner identifies the pupae based on their shoulder size or cephalothorax width – the females are bigger.

The process continues at the sex sorting room, where it takes about three to four hours to generate about 1 to 1.5 million male mosquitoes.

Step 5: Packing and transporting

This is the final step of the production cycle – where the mosquitoes are packed and transported for release.

About 200 male Wolbachia pupae are stored in a black container and packed into crates of 35 containers each. Since the mosquitos are still in the pupa stage, they are left inside for a few days to fully develop.

An NEA field officer then collects the crates and the mosquitoes are sent to various sites for release.

The NEA team is still learning from the current field trial for Project Wolbachia, Dr Ng said.

"For example, how best to release the mosquitoes? It is not just about releasing … We have to have tactics (on) how best to release so that it's more effective," she said.

"We don't know everything yet. The current trial will give us an idea of … the production scale that we need,” she said, adding that these lessons will contribute to a more cost-effective and sustainable programme for the long term.

Dr Duane Gubler, emeritus professor for the Programme in Emerging Infectious Diseases at Duke-NUS Medical School, pointed out that Project Wolbachia is “still in an experimental phase” and has not been upscaled to the whole country.

“Therefore, it is not expected to have an impact on overall dengue transmission yet,” said Dr Gubler.

Professor Tikki Pangestu, a visiting professor at NUS' Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, also highlighted that there are several challenges in scaling up the project countrywide. These include high costs, manpower requirements, potential negative ecological impact on the ecosystem as well as overcoming public concern if more mosquitoes are released.

MOSQUITOES NEED TIME TO GROW

On whether the process can be accelerated to produce more male Wolbachia-Aedes mosquitoes, both experts CNA spoke to agreed that would be needed to expand the project to the rest of Singapore.

However, NEA’s Dr Ng told CNA that the mosquito breeding process has a biological clock and the insects need time to grow on their own.

The process from an adult mosquito laying eggs to producing the next generation of adult mosquitos takes about four weeks.

“It's hard to say ‘I want to make it faster’ because it's their own process,” said Dr Ng, adding that NEA has “optimised” the process to produce good quality mosquitoes that are fit and able to compete in the field.

“The Wolbachia males that we send out (have) to be able to compete with those in the field. If they're … not as fit as the one in the field, the technology will not work.”

She added that it is not just the number of mosquitoes that matters, but whether the mosquitoes will survive long enough in the field to increase the effectiveness of Project Wolbachia.