Never Too Old: Retirement would be 'boring', says 93-year-old cardiologist still working full-time

What drives one of Singapore's pioneering heart specialists? In the first part of a series on elderly who choose to spend their golden years working, CNA speaks to Dr Charles Toh Chai Soon about his enduring love for medicine.

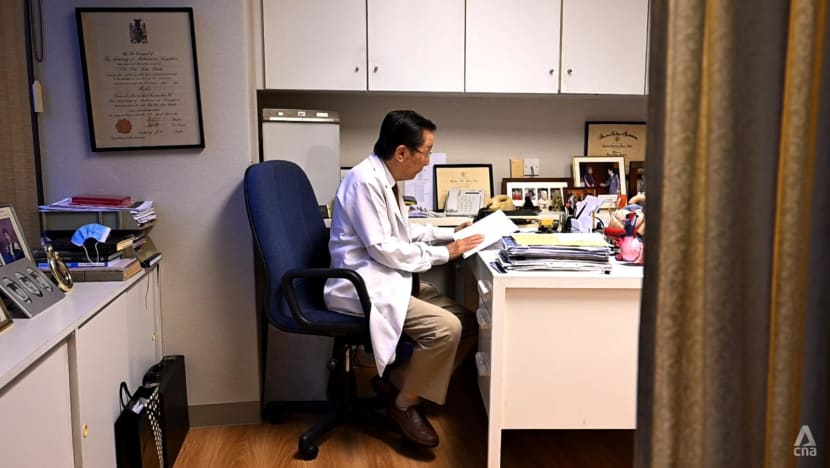

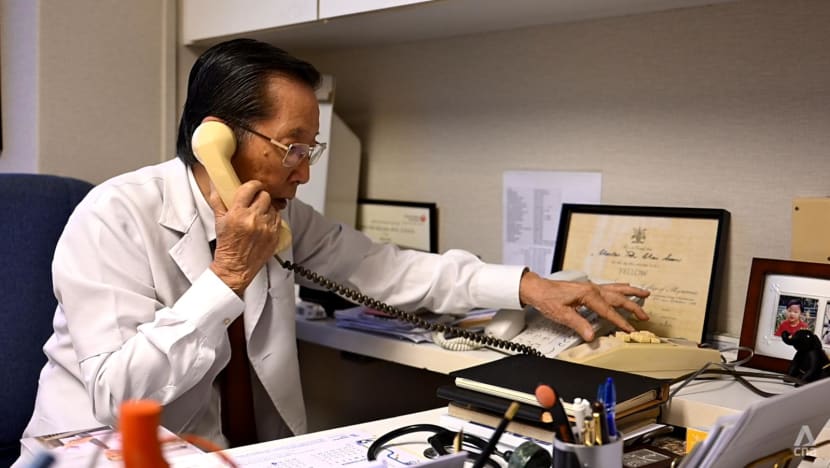

Dr Charles Toh Chai Soon, one of Singapore's pioneering cardiologists, at his clinic in Mount Elizabeth Hospital. (Photo: CNA/Jeremy Long)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: The second most surprising thing about the clinic of eminent cardiologist, Dr Charles Toh Chai Soon, is a handwritten sign wrapped in plastic and stuck to the registration counter.

It reads, in block letters: CASH PAYMENT ONLY.

Its existence feels antithetical to Singapore’s digital push, not least since the clinic is in Mount Elizabeth Hospital – a private hospital in Orchard Road – where it would be reasonable to assume patients coming to consult a heart specialist expect to pay by card.

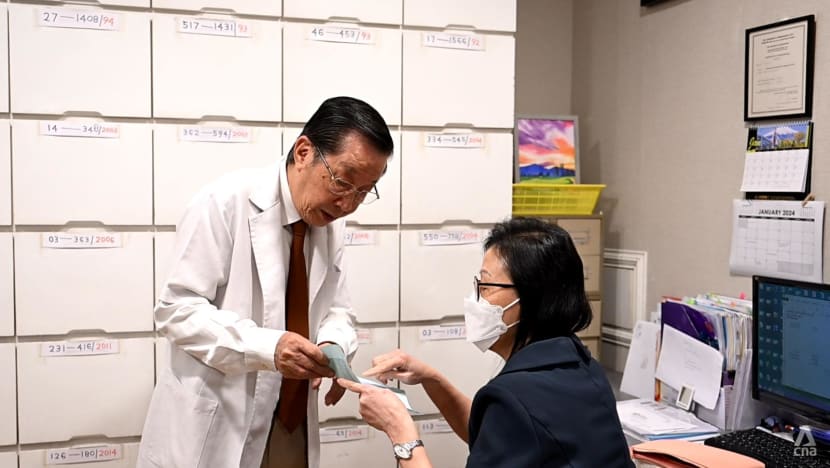

The sign appears less out of place, however, next to the floor-to-ceiling filing cabinets that store patients’ medical records. The records are handwritten, as are the labels on the drawers – a quirk that the receptionist endearingly calls “old school”, like her boss.

The most surprising thing about the Charles Toh Clinic is that its founder, Dr Toh, seven years shy of turning a century old, is still working full-time.

As a cardiologist, he is a consultant who specialises in the treatment and diagnosis of heart diseases. He is not a cardiac surgeon and does not perform operations. If he were a surgeon, he noted, he would have had to stop working a long time ago.

And god forbid anyone suggest that he take a break.

“Can you imagine doing nothing at all? Very boring,” he said when asked about retirement plans, repeatedly brushing off the prospect of calling it a day.

LOVE FOR ROUTINE

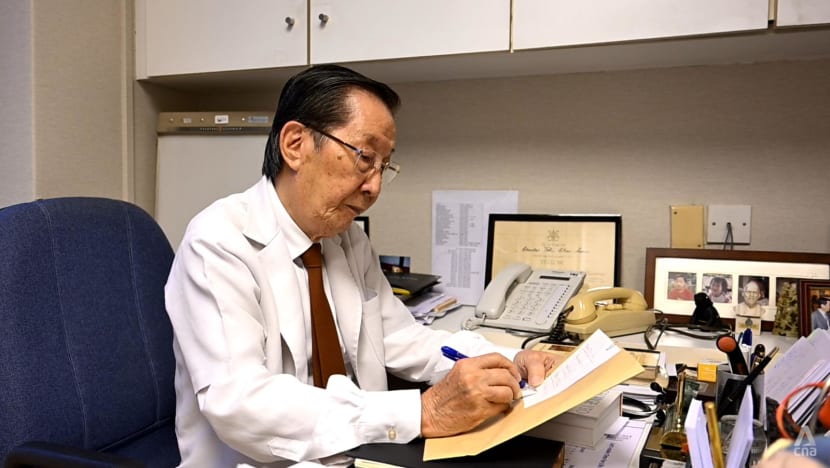

Having turned 93 last September, Dr Toh has mastered the science of sticking to a routine.

Every morning, he leaves home at 8am, arriving at work by 8.30am. He settles into his day by visiting his patients in the wards. If the wards are “quiet”, he heads to the doctors' lounge on the second floor to have breakfast before his clinic opens at 9am.

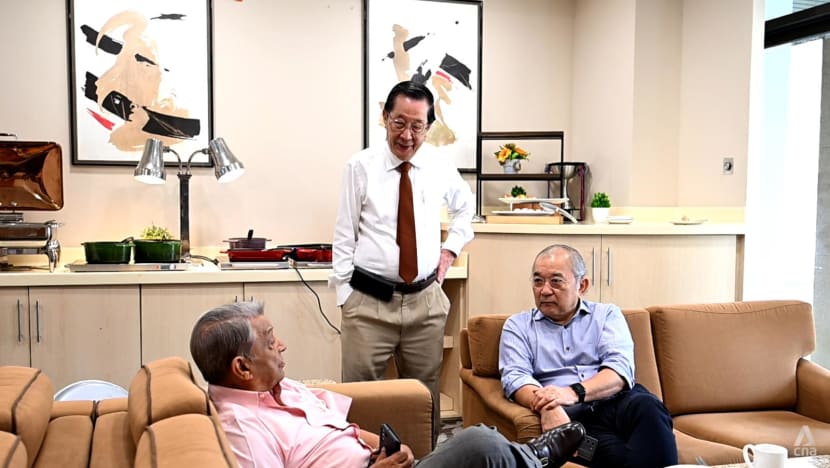

Come lunchtime, which is usually from 12.30pm to 2pm, he may take a teleconference call or spend his break in the doctors' lounge with other physicians.

When he feels like it, he goes to Lucky Plaza or Paragon shopping centre situated near the hospital to “jalan jalan” (take a walk), he said.

His afternoon routine mirrors his morning’s, except for Saturdays, where he only works half a day until 1pm. On weekdays, the clinic closes at 5pm. Before leaving the hospital, he usually visits his patients in the wards again.

Occasionally, he treats himself to a foot massage at Lucky Plaza before going home.

Understanding Dr Toh’s adherence to his routine is key to understanding the medical pioneer, who is credited for much of what cardiology is today in Singapore.

But he summarises his character simply: “Fairly disciplined” and “quite regimented in my way of life”.

His biography published by World Scientific Publishing, titled Heart to Heart, provides a more detailed explanation. In a chapter written by his second son, Dr Toh Han Chong, deputy CEO at the National Cancer Centre, the younger Dr Toh said his father has “an ascetic self-discipline, and is very punctual and precise”.

For instance, his father walks the dog in the evening at a particular time, the 60-year-old wrote, “and one can almost set one’s watch to when he starts doing this”.

His father is also “very fixed in his habits”, the younger Dr Toh elaborated in person. “He always plays golf on Sunday, and if it starts raining, he gets really upset because it breaks that cycle.”

The nonagenarian's commitment to stick to the course is also reflected in his sparing wants. He is “simple in his tastes and lifestyle” due to deep Japanese influence. During World War II, he was enrolled in a Japanese school in Ipoh, Malaysia, where he was born.

“Even till today, his lunch is usually a simple bento box,” wrote the younger Dr Toh. And in any Italian restaurant, his father would “almost always order spaghetti bolognese or carbonara”.

The older Dr Toh’s methodical nature also underpins his attraction to cardiology, a branch of internal medicine. The study of the heart is “almost mathematical”, he stated in his book.

While pursuing his postgraduate studies in the UK during the late 1950s, the young doctor chose to specialise in cardiology because it is based on “very exact parameters, with logical conclusions based on a fixed set of clinical assessment tests and investigations”.

Cardiology requires “you listen to the heartbeat and check the pulse”, he told CNA. “You calculate this, you calculate that, you do the ECGs (electrocardiogram) and so forth.”

A PEOPLE PERSON AT HEART

After moving to Singapore in 1960, Dr Toh worked as a junior consultant at the Singapore General Hospital’s (SGH) Department of Clinical Medicine. In his time at SGH, he was involved in developing its Department of Cardiology.

At the same time, Dr Toh was a lecturer; SGH was the main teaching hospital in the country then. In class, the cardiologist had a reputation for being fierce and wouldn’t hesitate to tell off students if they examined the patient wrongly.

One of his students, Dr Lee Wei Ling, the daughter of founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, “refused to be in my ward”, he recalled laughing. “Then her father asked why. She told her father, ‘I’m too scared of him.’”

There was no shortage of prominent figures in Dr Toh’s storied career, according to his biography, including some who were his patients. In 1968, for example, he was called to help care for Singapore’s first President, the late Yusof Ishak, who had been hospitalised for an irregular heartbeat.

And in his office today – alongside medical journals and magazines, Southeast Asian art and photos of his grandchildren – stand a couple of photos with his late friend and former President S R Nathan, whom Dr Toh remembers as a “very nice” man.

Despite his illustrious achievements, Dr Toh is perhaps living his best life in his golden years. Having forged a path for younger cardiologists and medical professionals to enjoy the fruits of his labour, he can now focus on what he loves most: Meeting people.

On a 10-minute stroll around his usual haunts in the hospital, he morphs into a tour guide, sharing the history of certain clinics and their specialists. Just before heading off for the day to meet a friend at Lucky Plaza, he runs into two young Malaysian workers from another clinic at the lift lobby – who light up as though they've met their grandfather – and doles out praise for Malaysians.

And in his office, a computer is noticeably missing from his desk. It would be a “distraction”, preventing him from giving undivided attention to his patient, Dr Toh explained matter-of-factly.

“I enjoy medicine. It’s so interesting because you’re seeing different people all the time. And of course, when you come to the hospital, you see your colleagues. You have tea and lunch together,” he added.

“As you get older, the volume of your patients goes down; it’s only natural. But I can’t imagine doing nothing at home. There are a lot of people who look forward to retirement, but once they retire, they find they are so bored.”

Dr Toh's wife died over a decade ago and his three children all have flourishing careers and families of their own, so he has even more reason to continue working.

Singapore's retirement age is “still quite young”, he said. “There are many people after retirement who still go into some kind of business with their colleagues or sit on some board.”

Dr Toh’s sprawling resume in his biography lists around 15 directorship or membership positions on statutory boards from 1968. This includes being chairman of the National Medical Research Council from 1994 to 2000 and deputy chairman of the Public Service Commission from 2010 to 2013.

“Dad was invited to join politics, but he said no because he enjoys seeing patients," the younger Dr Toh shared.

ACTIVE IN ALL WAYS

While Dr Toh believes one should remain physically and mentally active at all ages, he acknowledged that in some professions, there are “limitations” to continue working at his age.

For instance, a dentist or surgeon depends heavily on their hands and technical skills, making it unlikely that they can remain in practice in their 90s.

“Internal medicine is different because you’re giving an opinion; you’re not operating on people. Different professions have different demands, and in the end, expectations cannot be the same,” he said.

How, then, does one land a career fulfilling enough to work decades beyond the typical retirement age without burning out? There are only two things that should matter to young people, advised Dr Toh.

Their interest and their strength.

There is “no point” in having one without the other, he said.

“In the first place, you must choose the right career. When you choose one that isn’t your top choice, you may burn out earlier. The second point is, in certain careers, you have no choice (but to retire at a certain age).

“Of course, you may not think about all these things when you’re young … You only think about what you’re interested in.”

The problem, however, is that “as some people age, their mental abilities go down”, noted Dr Toh. If that happens with physicians, “it’s not easy to practise” as they could prescribe the wrong medication.

“Your mind has to be still intact – but to keep your mind intact is not the easiest thing to do.”

But Dr Toh’s mind isn’t merely intact enough to continue practising. He also takes pride in having “wider interests” than his profession – a necessity, he believes, for a long and fulfilling life.

“I read a lot about Southeast Asian cultures and history … and I love music. Music is one of my great loves. There is also some interesting biological evidence that listening to music is good for the brain. It keeps the mind going,” he said.

“Of course, being in touch with people is important too … having that interaction. Watching TV is too passive for me.”

Asked what he would like to be remembered for after his death, Dr Toh replied with a twinkle in his eye: “For leading a fulfilling, complete life.”

Towards the end of an hour-long chat, he gets restless – an extra spring in his step gives him away. He quickly but politely says his goodbyes before zipping off to his next appointment, for there is still more to do and much to live for.

If you have an inspiring story to share or information about something newsworthy, CNA wants to hear from you. Send us a message on WhatsApp or on CNA Eyewitness.