IN FOCUS: 'Be a man', do the right thing? Not so simple, say some in Singapore

Shifting expectations, unsustainable ideals, negative role models at every turn and uncertainty over how to behave around women: These are confusing times for masculinity, as CNA’s Ang Hwee Min finds out.

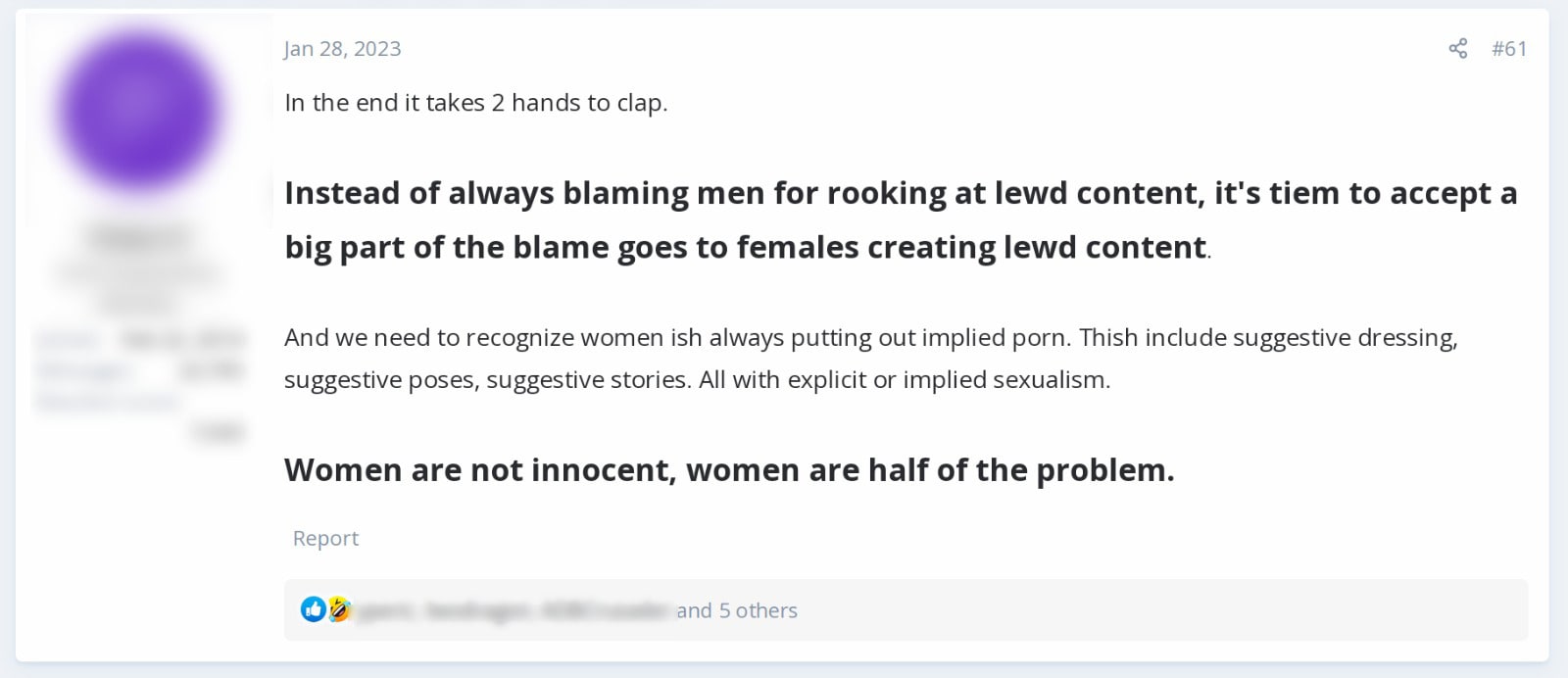

A YouGov poll for CNA found that Singapore residents considered "strong", "physically fit", "decisive" and "dominant" to be the most masculine traits. (Illustration: CNA/Lydia Lam)

Warning: This story discusses suicide.

SINGAPORE: Kevin Wee spent most of his schooling years being told he was “set for life”. He was driven, hardworking, good at his studies and athletic: Traits he saw as traditionally masculine, and valued by both his faith and family.

Growing up in what he described as a very conservative Christian setting also meant believing that men should head the household and women should submit to their husbands, said Wee, now 29 and an entrepreneur.

There were expectations that a man should excel, achieve, lead, provide, protect – expectations that ultimately proved too high, too much for him.

At his A-Level examinations, a severely anxious Wee suffered a mental block for the first time in his life and ended up turning in some of his papers blank. His self-esteem crumbled and he spent the next few months depressed and hospitalised with suicidal thoughts.

Wee’s parents supported him throughout but 10 years later, at the start of 2022, he faced another bout of anxiety and depression. This time, it was from losing a hard-earned S$200,000 when markets plunged in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

This was also when Wee found himself drawn to the controversial internet personality and ex-kickboxer Andrew Tate, known for his hyper-masculine and misogynistic views. “He would say things like it’s not how you feel,” said Wee. “If you want to be competitive in this world … as a man, your imperative is to go out there and do things, whether you feel like it or not.”

This thought process – that he had to just hustle, forget his emotions and go for success – initially motivated him but eventually put even more pressure on him, leading to a relapse in suicidal thoughts.

“Because I couldn’t live up to expectations anymore, I just didn’t think I wanted to live,” he said. “I just didn’t know what life was without … achievements, without that masculinity, if you want to put it that way.”

Several men CNA spoke to for this story were cognisant of traditional gender norms and the roles they were expected to play – but just like Wee, were less sure whether these lined up with what they really wanted for themselves.

In a YouGov poll of Singapore residents, conducted for CNA in September this year, just over 60 per cent of 512 male respondents aged at least 18 agreed that they fit in with what they thought were current gender norms.

Around 40 per cent agreed that traditional gender norms were outdated and ought to change.

Nearly four out of five male respondents agreed that a man should be able to support himself and his family financially. Close to a quarter said it was unacceptable for men to be stay-at-home fathers and to take care of children, while two out of five said they felt the pressure of fulfilling the role as man of the household.

The survey also asked 1,030 Singapore residents of all genders which traits they considered most masculine. Strong, physically fit, decisive and dominant emerged as the top few.

When asked to rate themselves on a scale from completely masculine to completely feminine, nearly a quarter of the male respondents said they were neither masculine nor feminine. Over one-fifth said they were feminine or completely feminine.

“WHY ARE YOU SOFT?”

Unsustainable ideals and mixed messaging have made it difficult to define the ideal man, resulting in an unattainable paragon, said Aarti Mundae, a psychotherapist with Incontact Counselling and Training.

“(Men) have grown up with an era of fathers who were conditioned in a certain way,” she added. “And the cultural and social context of the current environment has completely changed.”

Boys who imbibed from their dads and other male role models the importance of being a manly man, are now adults in a world asking – sometimes admonishing – them to embrace their more feminine sides.

No wonder “men are lost”, said Mundae.

Even if not adrift, they are fixated on either traditional masculine values or the other side of the fence where there is no separation between genders, which can also be complex and confusing, the counsellor said.

It is in this context where male mental health has also come to the fore, with men making up two-thirds of all suicide deaths in Singapore last year. The trend – of males outnumbering females in suicide deaths – is reflected globally, and research shows that societal expectations and mental health stigma are among potential contributing factors, said the Samaritans of Singapore in July.

Unsurprisingly, the men CNA spoke to for this story identified “strong and silent” as a particular stereotype they’ve had to deal with throughout their lives.

The YouGov poll showed the same. Nearly a third of male respondents found it difficult to express their emotions, while 64 per cent agreed it was acceptable to ask someone to “man up” or “be a man”.

Full-time National Serviceman Jasper Tan was told just that when he enlisted. He described being surrounded by fellow soldiers who believe that men have to be strong and not show weakness. This led him to dwell on whether to act tough and not display an emotional side, given that he wanted to be accepted and not bullied.

When some show vulnerability, remarks like “Why are you soft?” or “Why you so gay?” are commonplace, the 21-year-old said.

“I don’t support their comments, but sometimes when I correct them, it’ll be seen as a way of offending their manliness,” Tan added.

As an overweight kid in an all-boys school, Kristian Marc James Paul knows a thing or two about bullying.

He went on to develop deep insecurities about his body; and as a teenager, believed that the ideal man was a well-built, athletic model or bodybuilder – not unlike the fitness influencers exploding onto YouTube and Instagram at the time.

“(Those) insecurities came from me feeling like there was a big disjunct between who I was versus who I thought attractive men looked like,” said Paul, now 29.

He began thinking more critically about masculinity when he was formally diagnosed with body dysmorphia in 2015.

“What does it mean to be a man? What does it mean to embody ideal masculine characteristics?”

“MEN ARE LOVED SOLELY FOR THEIR ABILITY TO PROVIDE”

Johnathan Chua, co-founder of creative agency GRVTY Media and the youngest brother to two sisters, recalls being a crybaby as a child.

“I remember trying very hard to outgrow that … trying to be the tough guy so they no longer called me san jie (third sister in Mandarin),” he said.

The 33-year-old also hosts a podcast called The Daily Ketchup, where gender roles and norms are sometimes discussed in relation to current affairs.

To him, men can show vulnerability at times but “cannot give in (and) be too weak”; they also have to be strong to take up roles in society that women cannot.

This view doesn’t extend to household responsibilities, with Chua deeming it “really unfair” that his mother had to do the chores and care for the extended family while his dad just sat around watching TV – even though they both worked full time.

But being a provider is key to his notions of masculinity. Paraphrasing a line from one of comedian Chris Rock’s skits, Chua said in seriousness: “Only women and children are loved unconditionally. Men are loved solely for their ability to provide.”

He gave the example of a scenario where his business goes bust, and how his wife would have confidence in him recovering his career.

“If I don’t, then I do believe I will be abandoned, and I can see why,” said Chua. “I would think she deserves better if I don’t bounce back.”

For men, losing their primary identity, role and purpose as a provider may aggravate not just feelings of anxiety and stress, but also shame based on years of internalised cultural and societal expectations, said psychotherapist Kiki Mohan from Alliance Counselling.

They might think “I’m not good enough” or “I’m a failure”, and their self-worth takes a hit. It may also lead to feeling like they no longer belong to the heteronormative definitions of their social groups, she added.

“This could further perpetuate the behaviour of not being able to reach out and share this difficult experience with their family and friends, leading to further isolation.”

For several men CNA spoke to, however, it was their social circles that were reinforcing expectations of how a man should be.

Irshad Anguilla, 28, grew up with mostly male friends but after studying abroad, eventually came to find their crass jokes no longer funny. He argues with friends over comments they make about gender roles – for instance when they are intimidated by women more successful than them, or are unsure how to behave around women for fear of being cancelled.

The YouGov survey done for this story similarly found that nearly half of the male respondents worried about saying the wrong thing that may offend people of other genders.

Only 13 per cent said it was unacceptable for men to have a partner more successful than them, and 68 per cent agreed men and women should have equal rights.

Yet a not-insignificant proportion – 45 per cent – also felt that women have it easier than men these days.

GUIDED BY THE MANOSPHERE?

In Singapore, a cursory glance at local Reddit communities and forums like HardwareZone or Sammyboy will turn up hundreds, if not thousands of variations of the same complaint: Women being treated better than men; women privileged over men and so on.

And no topic is capable of drawing out as many – and as fervent – reactions as that of National Service, mandatory for all men in Singapore and for some, a source of resentment over the perceived unfairness of women not having to enlist.

The same hostility can be found among the male incel (short for involuntarily celibate) movement, where men blame women for their lack of romantic success. In overlapping spaces, women are also blamed for dressing suggestively and for being part of the problem when it comes to sexual crimes.

Many of these men are parroting rhetoric by Tate, the online provocateur who has compared women to property, and other figures – like Canadian psychologist Jordan Peterson and American podcaster Joe Rogan – within the wider “manosphere” subculture which promotes misogyny and toxic versions of masculinity.

Tate was also indicted in June this year for human trafficking, rape and forming a criminal gang to sexually exploit women.

He has denied the allegations and men of his ilk persist, for entire swathes of the male population, as role models to be idealised and idolised.

Wee, the entrepreneur, told CNA he was “hooked” on Tate’s content – but only his takes on self-improvement and how to run a business, and not the misogynistic comments.

Yet the Singaporean, who now runs training programmes for students, acknowledged he was concerned about Tate’s popularity among the primary and secondary school kids he meets.

Surveys in the West report boys having positive opinions of Tate, and some schools in the United Kingdom have adapted their syllabus to combat his views.

When asked by CNA about such online male role models, Singapore’s Ministry of Education said it regularly reviews its character and citizenship education curriculum to ensure its relevance amid the rising influence of social media.

The ministry also noted the importance of parents in guiding children to be discerning in the digital space.

A spokesperson for the Centre for Fathering non-profit told CNA: “Fathers who are positive role models provide a sound perspective to counteract extreme or unrealistic portrayals often seen on social media. This helps children differentiate between curated online personas and the realities of life.”

WHITHER FATHER FIGURES

Men CNA interviewed for this story said they looked to their father as a prime example of how to be a man, though some cited influential female figures in their lives.

The YouGov survey found that 45 per cent of male respondents aspired to be the kind of man their father or grandfather was. More than a quarter said they had a male role model whom they found difficult to emulate.

For undergraduate Ng Zhong Han, his concept of ideal masculinity – being a reliable provider – was largely shaped by his dad, who is the sole breadwinner and “handyman” of the household among other hats.

The 23-year-old said he was beginning to question such norms and assumptions, but still aspired towards them.

“A lot of men don't seem to have a handle on what really defines authentic manhood, as in masculinity … on who they're supposed to be as men,” said therapist Ivan Lee, adding that some try to answer this through “less than ideal” sources such as absent or abusive dads.

“Boys and men are more likely to become emotionally unstable and experience depression, anxiety about their identity .. if their fathers are absent during their growing years,” the Centre for Fathering spokesperson said.

“Sons tend to model after their fathers when they become fathers themselves. Many fathers enter parenthood without reflecting on how they were raised by their fathers.”

In an interview with CNA, Minister of State for Trade and Industry and Culture, Community and Youth Alvin Tan said he and his wife are conscious of narrow gender stereotypes when they speak with their two children aged 11 and 9.

“Sometimes you blurt it out, and then you think, actually, let me rephrase that a little bit,” he said, adding that he would then explain to the kids why. Mr Tan, who has a son and a daughter, is keen for his children to know that their abilities do not depend on their gender.

Having joined politics in the most recent General Election in 2020, Mr Tan has built a reputation for social media savvy and openness. The 43-year-old is not shy about sharing vulnerable moments such as fretting over not spending enough time with his children – a move that was met with some pushback from older generations, but helped others relate better to him.

“If it helps to show us as humans and that we have frailties, it’s okay … it’s okay to be sad sometimes, or discouraged, or tired,” he said. “In fact, it shows strength because you’re comfortable in your own skin and that there’s some degree of self-esteem or self-assurance.”

WHAT MASCULINITY TO ASPIRE TO?

Traditional expectations for men – to be strong, self-reliant, unemotional and to use dominance to assert control in getting what they want – are narrow and harmful, according to the Centre for Fathering.

Instead, men should demonstrate qualities such as kindness, interdependence, empathy and respect in their interactions with others.

“Healthy masculinity”, the spokesperson from the centre added, can be observed through accountability, humility and a willingness to learn from mistakes, seek feedback and grow.

For Mohan, the mental health practitioner, it is also about expressing a full range of emotions and vulnerability, and asking for help when needed.

If men can call out other men who engage in toxic behaviours, this can go a long way in systematically reducing the challenges around gender roles and identities, she added.

Just as helpful is having communities where men can talk about their feelings openly without judgment and seek support.

Men in Singapore have recognised this need. Therapist Kester Tay and local musician Lewis Loh launched Conscious Brotherhood this year, an initiative where men are invited to gather to discuss – in confidence – topics relevant to their gender.

“As men, we are relied on a lot,” said Tay. “But there are very few places where we can rely on others.”

Before each session, participants are polled on what topics they would like to cover. In the first two gatherings, Conscious Brotherhood has covered what it means to be a man and how to set healthy boundaries, and are hoping to next explore self-love and anger.

Thomas Heng, 47, also runs an informal men’s group that has been going strong since 2014.

A male friend had spent hours on the phone counselling and helping him through depression and a string of failed relationships. After meeting others who were going through what he did, Heng was compelled to go on meetup.com and set up a space for men to gather every fourth Friday of the month.

“In my time, I only had the suicide hotline. Nobody talked about mental health, so I thought, I know what I can do,” said Heng. “I just create a community, I’m there to facilitate, and when they’re there, they learn from others. That’s the power of conversation.”

Towards the end of a two-hour interview, Wee, the businessman, admitted he was still struggling with internalised, gendered expectations.

“I am still very competitive … But I’m also self-aware enough to know that that is based out of possibly a lot of insecurity and a need for validation,” he said.

What then, to him, does healthy masculinity look like; a masculinity that he can confidently affirm in his telling of a dog-eat-dog world?

Wee laughed nervously at the question, and paused for a few minutes. “It’s being mentally, spiritually and physically strong, knowing that that strength can come, occasionally, from vulnerability.”