China Power: Welcome, wariness - a rising Beijing reshaping perceptions among ethnic Chinese in Southeast Asia

As part of a series on China’s regional influence, CNA visited Vietnam, Malaysia and the Philippines to speak with ethnic Chinese communities. Their views reveal a mix of pride, pragmatism and concern.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

BAC NINH/MANILA/MUAR: Nicole Dang stands behind the counter of her Taiwanese specialty restaurant, greeting customers with a warm smile as the aroma of braised pork and fragrant tea fills the air.

At 40, Dang is both an entrepreneur and a bridge between cultures. Born in Vietnam’s Ho Chi Minh City to ethnic Chinese parents, whose own families migrated from China’s Guangdong province in the 1940s, she grew up immersed in both countries’ traditions.

Learning Mandarin, however, was a challenge, she recalled, as the language was not a standard subject in Vietnamese schools.

“I cried every time I had to go for Chinese tuition after school. But resistance wasn’t an option - I knew if I refused, my dad would punish me.”

At this point, her father, Vinh, sitting across the dining table in their family restaurant, interjects. “I was harsh because, after all, we are Chinese,” he said firmly in Mandarin.

“I want my children to always remember their roots,” said Vinh, who ensured all five of them underwent the same cultural upbringing.

Willingly or not, the lessons have paid off for Dang. Since moving to Bac Ninh in the eponymous Vietnamese province a decade ago, fluency in Mandarin has underpinned her business ventures as the city becomes one of the country’s hottest hubs for Chinese money and nationals.

Beyond running a restaurant, Dang co-owns a supermarket specialising in Chinese and Taiwanese goods. Their main clientele: Chinese workers, investors and professionals who have made Bac Ninh their home in recent years.

“They long for the taste of home,” Dang told CNA. “I understand that feeling well - having spent years studying in Taiwan, I know what it’s like to crave familiar flavours.”

As China’s presence grows across Southeast Asia, local Chinese communities find themselves at the crossroads of its widening influence.

Evoking welcome and wariness in uneven parts and reshaping perceptions from local Chinese, the phenomenon was once again captured in the annual State of Southeast Asia survey by ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, a Singapore-based research centre.

China remains the most influential economic and political-strategic power in the region, outpacing the US significantly - albeit with reduced margins compared to 2024, noted the report, which canvassed just over 2,000 respondents across the region.

“Despite China’s positive standing, the region’s concern about its growing economic and political-strategic influence outweighs its acceptance,” stated the report, now in its seventh year.

The US has also dislodged China in being the prevailing choice if the region were forced to take a side, according to the survey, reflecting shifting strategic alignments amid growing superpower rivalry.

Analysts say Beijing needs to be even more aware of regional sentiments and manage them carefully as geopolitical tensions and great power rivalry intensify, supercharged by a second Donald Trump presidency in the US.

That’s especially true as China’s growing assertiveness in the region, notably its actions in the contested South China Sea, stokes unease among Southeast Asian states and raises questions over Beijing's agenda.

FROM FARMLAND TO FACTORIES

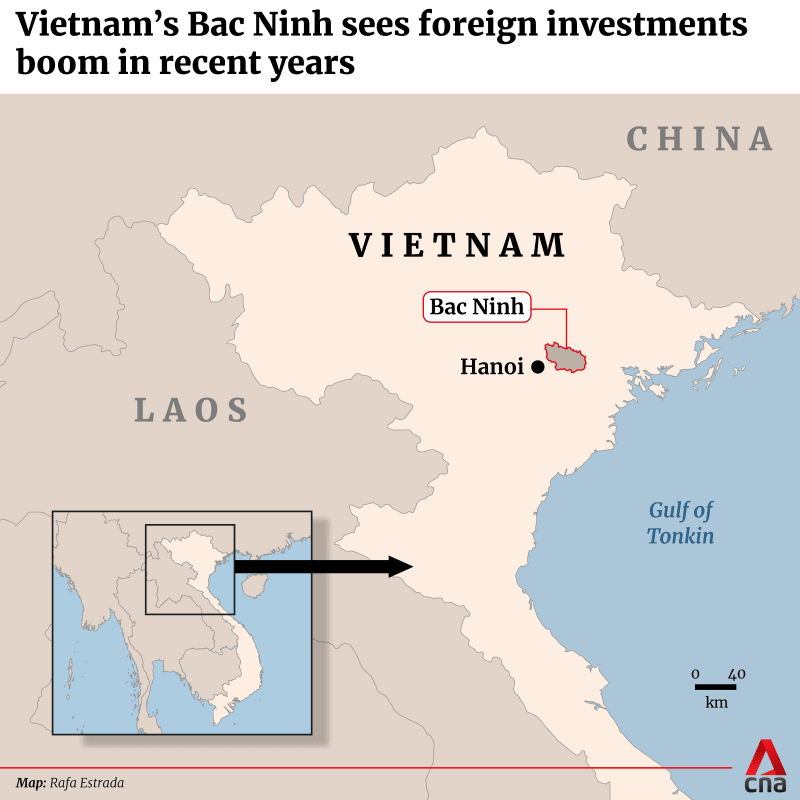

An hour’s drive north of Hanoi, Vietnam’s capital, Bac Ninh was once a rural province centred on agriculture.

Today, it has transformed into a vibrant hub for businesses and expatriates, with a large portion of newcomers from China and the rest primarily from places such as South Korea and Taiwan.

Bac Ninh was Vietnam’s top foreign direct investment (FDI) destination last year, drawing nearly US$5.12 billion in registered capital, according to official data.

This accounted for 13.4 per cent of Vietnam’s total FDI, a sharp rise from 2023 when the province ranked seventh with US$1.76 billion.

China is a key investor in the country. In January this year, it ranked fourth in total foreign investment. South Korea led with US$1.25 billion, a 13.4-fold increase from the previous year, followed closely by Singapore and Japan in third place.

One of Bac Ninh’s major investors is Goertek, a leading acoustic components manufacturer.

The Chinese company has invested over US$1.3 billion in the province. Goertek chairman Jiang Bin has already announced plans to significantly expand the firm’s investment in Bac Ninh, potentially tripling or even quadrupling its current financial commitment.

Major cities in north Vietnam are now far better connected, highlighted Dang the entrepreneur.

“With new expressways built in recent years, there’s direct access to the Chinese border, making the movement of goods more affordable, and also streamlining manpower resources.”

As foreign investments flow into Bac Ninh, so too have foreign expatriates and workers. Some 100,000 of them reside in the province, according to preliminary estimates from local officials last year. Local media reports suggest that at least half of them are from China.

Bac Ninh has a population of approximately 1.24 million, with the city of the same name home to around 288,000 residents, according to official statistics.

This trend has also fueled a form of reverse migration, with ethnic Chinese who have long resided in southern Vietnam now heading north in search of new opportunities - Dang among them.

“I never imagined I’d move to the north,” she said, highlighting the fraught landscape for ethnic Chinese in northern Vietnam half a century ago.

In the late 1970s, a wave of ethnic Chinese, known as the Hoa, fled Vietnam as tensions between Hanoi and Beijing deepened. Allegations of persecution and discrimination mounted, particularly after Vietnam invaded Cambodia in late 1978, which further strained its already fraught relationship with China.

In the present day, Vietnam’s ethnic Chinese population stands at fewer than 800,000, accounting for approximately 0.8 per cent of the country’s total population, according to official demographic data.

“Back then, my father had to change his name just to avoid being identified,” Dang said.

RIDING ON THE CHINESE WAVE

In Bac Ninh city, Vietnamese from all walks of life are eager to ride the wave of opportunity and cash in on growing Chinese money and manpower.

Ngo Thuy, general manager of HK International Language School, located along Bac Ninh’s bustling “China Street”, says demand for Mandarin courses has surged.

“In the past three years, our student intake has grown by at least 30 per cent annually,” she revealed, attributing the rise to post-pandemic economic momentum driven by Chinese investments.

It’s unclear exactly how many ethnic Chinese are picking up Mandarin to advance their careers in Bac Ninh. Thuy explained that language centres don’t typically track students' ethnic backgrounds.

But she has noticed a trend.

“Many students come in with a basic grasp of Mandarin,” she said. “What they want is industry-specific training or professional business fluency to gain a competitive edge.”

Learning Mandarin was a conscious decision for 24-year-old Hoang Dieu Linh, a hotel front desk operator who moved to Bac Ninh a year ago.

Despite her ethnic Chinese heritage, she never spoke the language growing up - her family communicated in a lesser-known southern Chinese dialect.

Determined to adapt, she turned to online courses for the basics before enrolling in advanced classes in Bac Ninh to refine her Mandarin proficiency.

Linh hails from Lang Son, a mountainous province in northern Vietnam, where job opportunities are scarce, mostly limited to farming and traditional crafts. There, she earned at best about eight million Vietnamese dong (US$318) a month. In Bac Ninh, she now makes about 30 per cent more.

“It’s not just the income, it’s (also) the quality of life,” she says. “Here, I meet people of different nationalities. It broadens my perspective.”

NOT JUST FUNDS, BUT FAITH

It’s not just workers and businesses flocking to Bac Ninh in search of new opportunities - the province has also become home to northern Vietnam’s only Chinese Christian church.

Tang Nguyen Tien, an ethnic Chinese born in Ho Chi Minh City, first arrived in Hanoi in 2010 to establish a Christian church for the Mandarin-speaking community.

But after years of struggling with tight restrictions on religious activities and a small congregation - below 50 at its peak - the 73-year-old took the bold step of relocating the church to Bac Ninh in 2023, drawn by the city’s rapid transformation and its growing Chinese-speaking population.

“Hanoi, being the political centre of Vietnam - a communist state, had strict regulations on setting up new religious organisations,” Tien explained to CNA.

“We couldn’t run most of our outreach programmes openly, and because there were so few believers who spoke Mandarin (in northern Vietnam), our congregation remained small.”

But in Bac Ninh, she saw a chance for a fresh start.

“I knew there would be significantly more Mandarin speakers here,” she said. “This is a brand new chapter for us - the only Chinese church in northern Vietnam.”

At its new location, the church’s congregation has grown from scratch to more than 20 members in under a year, and Tien has ambitious plans to expand.

She is currently raising funds to acquire a five-storey building, now rented, to serve as the church’s permanent home, located just five minutes from the city centre.

Her goal is to solidify the church’s presence and expand its community in the years ahead.

Even as locals benefit, some are cautious about a growing mainland Chinese presence.

Dang, the ethnic Chinese entrepreneur, highlighted rising manpower costs, attributing this to competition from large Chinese firms that have the resources to offer better salaries and working conditions, attracting a skilled workforce.

"We hope the government will consider measures that could level the playing field, allowing smaller local businesses like ours to survive and thrive," she said.

Safety is on the mind of 43-year-old Nguyen Thanh Thao, a restaurant floor manager at a Chinese-owned hotel in Bac Ninh city and a mother to two teenage daughters.

She told CNA she was concerned about rising crime and vice in the city, which she linked to the surge in entertainment venues accompanying the influx of large foreign firms and factories.

"We can't have the best of both worlds; this is expected with such a surge in business activity," said Thao, who traces her lineage back five generations to Guangdong, China.

“I just hope any potential illegal activities don’t spiral out of control and create lasting social problems."

PLACING NATIONALITY OVER ETHNICITY?

Far from being isolated to Vietnam, such mixed blessings and sentiments towards China have also been observed in other Southeast Asian nations.

In the Philippines, most of the ethnic Chinese community identify as Filipinos first, pointed out Filipino civic leader Teresita Ang See, an ethnic Chinese born and raised in Manila.

“The cradle of our organisation says our blood may be Chinese, but our roots grow deep in Philippine soil. Our bonds are with the Filipino people,” Ang, who manages operations at the Museum of Chinese in Philippine Life in downtown Manila, told CNA.

Ethnic Chinese make up around 1.8 per cent of the Philippine population. This is around 1.2 million people in absolute numbers, one of the smallest ethnic Chinese communities among Southeast Asian countries.

The identity and allegiances of this relatively small community have recently been cast in the spotlight amid brewing tensions between China and the Philippines in the South China Sea.

Maritime confrontations have been frequent as Manila, under President Ferdinand Marcos Jr, pushes back at what it sees as aggression by Beijing. China, which claims most of the South China Sea, has accused the Philippines of repeated encroachment in its waters.

Ang, also the former president of the Philippine Association for Chinese Studies, said she is “conflicted” over which side to take in this dispute as she feels that both countries have legal merit in their territorial claims.

Even so, she believes that the Philippines, as an Asian country, will benefit from having strong relations with a regional superpower like China rather than with the US.

“We have much to learn … much to benefit from China. If only we can learn to work together,” said Ang.

“Sovereignty is non-negotiable for the Philippines or China, so the solution is more diplomacy and negotiation. If we can set aside the differences, I strongly believe the ties that bind us together are much, much stronger than the differences that separate us.”

Similarly, in Malaysia, members of the ethnic Chinese community place nationality above ethnicity.

Ethnic Chinese comprise almost a quarter of Malaysia’s total population - equivalent to more than 7 million people. They are spread across different areas, concentrating in urban cities.

Lim Teck Guan, president of the Muar Tiong Hua Association, told CNA that Malaysian Chinese embrace their cultural roots but are keen to distinguish themselves from mainland Chinese.

“I am proud to be ethnic Chinese … we embrace our cultural roots and practices – cultural dances and processions are part of this,” said Lim, who runs a dentist clinic in the Johor district of Muar.

“But we are also proud to be Malaysians, bangsa Malaysia,” he said. Bangsa Malaysia refers to the country’s inclusive national identity for all citizens, regardless of race.

Lim noted that many Chinese tourists have earned a poor reputation for being boisterous and rude, unlike the Malaysian Chinese, who are already well-assimilated to Malaysian society and cultural norms.

“We are not like mainland Chinese at all, we are different. We speak Malay, we have neighbours and friends who are Malay, and we respect that Malaysia is a country that is predominantly Malay and Islam is the main religion,” he added.

INSTANCES OF DISCRIMINATION

Given that ethnic Chinese form the minority race in most Southeast Asian countries, some of them acknowledged that they have faced discrimination - especially as China’s regional influence grows.

This is particularly so in the Philippines amid tense bilateral relations with China.

The Marcos administration has clamped down on illegal offshore gambling operations, some of which are believed to be Chinese-backed.

Issues like the Alice Guo controversy - the former Philippine mayor who has been arrested and accused of being a Chinese spy enabling illegal gambling - have further intensified scrutiny on Filipino Chinese, said Ang, the ethnic Chinese Filipino civic leader.

“They can’t distinguish us from the new immigrants … you see this kind of racial profiling, especially these days when (such) issues are coming up. So they tend to see a Chinese person and then they say, ‘you are Chinese, you should leave our country’.”

Chinese Filipino Wilson Lee Flores, who is a writer and owns a bakery-cafe in Davao, told CNA that he has been accused by some locals of being a “pro-China spy” because he had invited a Chinese diplomat to give a political talk in his establishment.

He explained that his cafe has hosted various political talks and debates as he believes they foster political engagement. However, he stressed that he has been careful to be fair and invite speakers with different political leanings to speak.

“Many people (accuse me) of being pro-China but they forget that I have welcomed US ambassadors to speak here … everybody is welcome,” said Lee.

“(It’s becoming) a little bit worrisome for the ethnic Chinese minority, because some people cannot distinguish, they blindly think: ‘Ah, your ancestors are from China, you must be pro-China,’ which is not the reality,” he added.

In Malaysia, Lim’s Muar Tiong Hua Association recently received flak because the organisation’s procession in Muar on Jan 18 featured a dragon puppet with China’s flags hanging from its left flank.

Videos and images of the dragon went viral, prompting a police investigation and public calls for Malaysia’s king and Johor’s regent to take action.

Displaying a foreign flag in public or at schools is an offence under local laws, punishable by up to six months’ imprisonment and/or a fine not exceeding RM1,000.

According to Lim, the whole issue was a misunderstanding and everything has been settled with the authorities.

He told CNA, however, that he was “a bit surprised” that the issue made national headlines and attributed this to heightened racial sensitivities in the wake of other recent incidents.

“China and Malaysia recently celebrated the 50th anniversary of diplomatic relations (in 2024), so there were many performances and events celebrating the closeness of these two countries. So some members did not think much of it when we saw the ... (China) flags in the procession … but when it became a police case, we realised the issue is sensitive,” said Lim.

“We live in Malaysia and racial issues have become more sensitive recently. We have to respect this, and be more careful,” he added.

NAVIGATING REGIONAL SENTIMENTS

Highlighting the broader Southeast Asian landscape, Nguyen Khac Bao, a history and literature scholar based in Bac Ninh, said China must tread carefully amid lingering distrust and heightened geopolitical tensions.

"When it comes to building business ties or maintaining bilateral relations, trust is the foundation," he said.

"If prevailing sentiments contradict that, those contradictions may eventually become more pronounced in the wider society."

According to the State of Southeast Asia 2025 report, ASEAN continues to view China as the most influential economic (56.4 per cent) and political-strategic (37.9 per cent) power in the region.

Compared to last year, scepticism among ASEAN states in China’s ability to “do the right thing” in contributing to global peace, security, prosperity, and governance also eased slightly to 41.2 percent from 50.1 percent.

At the same time, the report found that member states are divided in their trust towards China.

Except for Brunei, Cambodia, Laos and Thailand, distrust towards China among the remaining six ASEAN member states remains higher than trust.

Among those who distrust China, 47.6 per cent believe that its economic and military power threatens their countries’ interests and sovereignty.

“This view is particularly strong in the Philippines (69.9 per cent) and Vietnam (53.2 per cent), where escalating territorial disputes with China in the South China Sea have intensified in recent years,” noted the report.

“These evolving perceptions reflect a mix of optimism about China’s economic prospects and pessimism surrounding geopolitical tensions, which are important factors that will continue to shape ASEAN’s long-term perceptions of China.”

One of the key downside risks for Vietnam is being “caught in the crossfire of the power struggle between the world’s two superpowers”, said Quan The Duc, a China observer and former university lecturer who taught Chinese language, history, and culture for nearly two decades.

There are growing concerns that Vietnam may be forced to choose between neighbouring China and a geographically distant yet influential America, said Duc, an ethnic Chinese born in Hanoi.

The latest State of Southeast Asia survey saw the US overtaking China to become the prevailing choice (52.3 per cent) if the region were forced to take a side.

China as a choice dropped to 47.7 per cent, down from 50.5 per cent in the previous year.

Slightly over half of the survey respondents believe that ASEAN should enhance its resilience and unity to fend off pressures from the two global powers, the report stated.

Chinese investors poured nearly US$4.5 billion worth of investment into Vietnam in 2024 - a 78 per cent year-on-year increase.

“My assessment is that when the time comes, Vietnam's ‘bamboo diplomacy’ will be put to the test,” Duc remarked, quoting the Chinese proverb “yuan qin bu ru jin lin” - meaning “a kin living far away is not as good as a neighbour nearby”.

Read the other articles in this series here:

Bamboo diplomacy refers to Vietnam's longstanding approach of standing firm on key foreign policy principles, such as sovereignty, while remaining adaptable in its practices.

Duc assessed that many ordinary Vietnamese and businesses feel it may be more in Vietnam’s interest to maintain close ties with China, due to geographical proximity as well as shared cultural and historical ties.

"As Vietnamese citizens, we must trust our government to navigate this delicate balance - welcoming Chinese investments while safeguarding the nation's interests.”

AMID WINDS OF CHANGE, ETHNIC CHINESE REFLECT

For the ethnic Chinese who have long called Bac Ninh home, the growing Chinese presence in their hometown is a mix of opportunity and reflection - energising the local economy while also stirring memories of an uncertain past.

Having witnessed their community’s struggle in the late 1970s, there is a sense of progress. Yet, it also serves as a poignant reminder of their troubled past and the complex relationship they’ve long had with their ethnicity in Vietnam.

In the quiet riverside town of Dap Cau, where the Cau River marks the boundary between Bac Ninh and neighbouring Bac Giang province, retired boat owner Thai Quoc Binh has spent his life watching the tides change - both on the river and in his hometown.

The 56-year-old, who still lives in his ancestral home, hails from China’s Fujian province. His family is among the last remaining ethnic Chinese in the town, a community once far larger but thinned by history.

As a child, Binh was too young to fully grasp the upheaval that sent waves of ethnic Chinese fleeing Vietnam. But the stories lived on in his parents’ recollections.

“(Our family) had also wanted to leave,” he said, pointing to an aged photograph of his parents and the wooden boat they had prepared for their escape, still hanging on his wall. “We were ready. But just when we were about to make our move, we were stopped.”

"I remember my parents lamenting at times, wishing the Chinese government back then had done more to help us leave Vietnam," he recalled.

Historical papers from the Journal of East Asian Affairs detail China’s attempts to evacuate ethnic Chinese from Vietnam during the late 1970s. Unarmed ships were dispatched to aid those seeking to leave, but diplomatic roadblocks emerged.

The Vietnamese government denied allegations of persecution and, as the number of repatriation requests surged, it eventually refused to issue exit permits, leaving many stranded.

Now, decades later, Binh finds himself witnessing a different kind of movement - one that brings more Chinese people into the town he never left.

When asked if he still identifies as Chinese and how he feels about Bac Ninh’s transformation, Binh responded with a series of firm nods, praising the economic opportunities that have lifted livelihoods across the province.

What stands out to him, however, is a shift in how the Vietnamese government treats its ethnic Chinese population. The tumultuous years of the late 1970s are long past, he noted, and there has been a noticeable positive change in attitude in the last two to three decades.

Binh pointed out that over the past five years, the Vietnamese government has increasingly consulted ethnic Chinese residents on issues like the repurposing and relocation of community buildings.

He noted that in the past, ethnic Chinese residents were largely excluded from consultations on municipal-related issues.

“I wouldn’t say there’s a direct connection between the (Chinese) investments and the government’s approach towards our community,” he said. “But it’s a good thing - not just for us, but for the entire country. And I’m immensely proud of that.”

Determined to see the next generation thrive, Binh has been urging his children and grandchildren to embrace their heritage.

“Learning the Chinese language and culture will only help them,” he said.

“It’s a clear advantage for their future.”