Commentary: Time for ASEAN to court new partners in its web of free trade agreements

Southeast Asia risks being hit by a double whammy in this US-China trade war, but the region has its own ammunition too, say William Choong and Sharon Seah from ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: On a research trip in the middle of April, we found ourselves in Washington, bathed in springtime sunshine, with smiling tourists taking photos outside the White House. Speaking to US government officials and think tank analysts provided us quite a different picture: The raft of “Liberation Day” tariffs announced just days earlier, they said, was “an exercise in unbridled chaos”.

Now that the US and China are finally starting trade talks this weekend, there is some hope that weeks of brinksmanship between the world’s two largest economies might finally give way to something constructive.

Both sides need a deal. For Southeast Asia, it must be a deal that does not create more collateral damage, better still a deal that does not force countries to walk a tightrope between the two strategic rivals.

Southeast Asia worries about becoming the dumping ground for excess Chinese goods, about being forced to cough up exorbitant tariff fees to continue exporting to America, and the expectation to impose trade or investment restrictions on China.

It’s really all about China. American officials are brutally frank when it comes to Southeast Asia. They don’t hide their disinterest in the region.

The Trump 2.0 administration is focused on righting the “wrongs” of trade imbalances between the US and its trading partners. For now, it is less concerned about Washington’s strategic approach to Southeast Asia and the Indo-Pacific. Any ounce of interest comes in the form of lamenting the region’s sanguine approach to China, when Washington is keen to line up a defensive perimeter around China.

A COHERENT CHINA STRATEGY, OR LACK THEREOF

Yet it does not appear that Mr Trump has formed a coherent China strategy, apart from what is effectively a trade embargo on China and using tariffs to exert pressure on everyone else to limit their relationship with Beijing.

In the interim, it appears that the US’ lazy default on Taiwan and the South China Sea will be implicit deterrence. One think tank analyst reminded us of his favourite Trump quote about his relationship with Chinese President Xi Jinping: “I wouldn't have to (use military force), because he respects me and he knows I'm f****** crazy,”.

But Washington cannot have a coherent China strategy if it does not have at least some Southeast Asian cooperation or acquiescence.

The Indo-Pacific is the world’s new centre of gravity, and Southeast Asia lies at its core. The region’s economy will eventually reach US$4.5 trillion to become the world’s fourth biggest economy come 2030, overtaking economic powerhouses like Japan and Germany. With ASEAN and its related entities such as the East Asia Summit in its diplomatic toolkit, the grouping exercises some form of convening power among the major powers.

Southeast Asia also sees the US as a way to balance China, as suggested in the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute’s 2025 State of Southeast Asia Survey. A significant portion of respondents welcomed Mr Trump’s strongman persona and his ability to stand up to China’s aggression, particularly in the South China Sea, though it should be noted the survey was conducted before “Liberation Day”.

The centre cannot hold, however. Speaking at this year's edition of the S Rajaratnam lecture in April, Singapore Prime Minister Lawrence Wong underscored how the post-World War II rules-based international order was fraying, given that the US is retreating from its traditional role as the guarantor of global order and no country is able to fill the void.

COURTING PARTNERS INTO EXISTING TRADE PACTS

A changed global order does not mean that Southeast Asian countries have no agency. The region is not without ammunition in the ongoing trade war between China and the US.

Courting trading partners who are looking for alternatives in the face of US tariffs is one. ASEAN may be a distinctive group of 10 economies but it has spun a complex web of bilateral and regional free trade agreements (FTAs) together as a collective grouping.

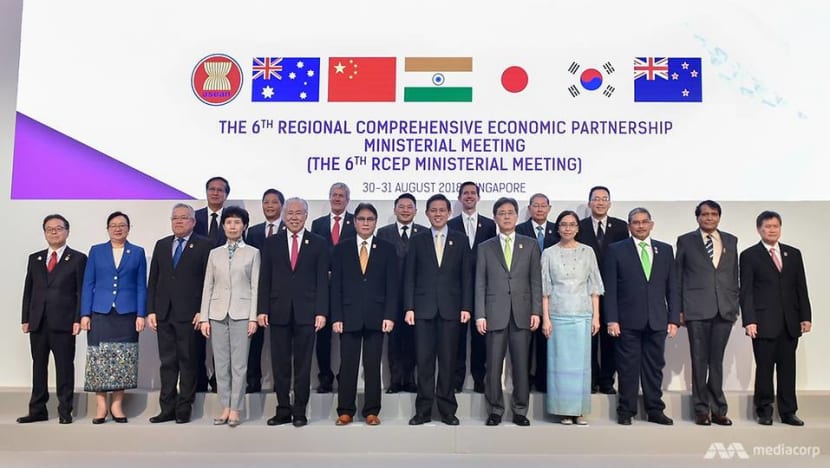

These include the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the world’s largest FTA comprising 30 per cent of the world’s total GDP and population. Four ASEAN countries are also part of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the precursor of which was abandoned by the first Trump Administration.

ASEAN’s proposed Digital Economic Framework Agreement, the world’s first regional digital economic trade agreement, could be another game changer in the burgeoning digital services trade.

Despite on-off talks of an FTA with ASEAN, the EU has held back due to reservations about ASEAN’s ability to harmonise and meet up to stringent EU trade, environment and human rights rules. The perfect cannot be the enemy of good. It would be timely for the two blocs to revive and accelerate these talks.

The EU also needs to consider if joining the RCEP and CPTPP could help to bolster its own trade resilience and strengthen its equally precarious trade position vis-a-vis the US. Similarly, an expansion of the CPTPP – which Indonesia, China, Taiwan, Costa Rica, Uruguay and Ecuador have applied to join – would serve to extend and strengthen trade linkages between Asia, Latin America and Europe.

The real cherry on the cake will be getting India to join the club. It is the fifth-largest economy by gross domestic product and soon-to-be the world’s third-largest consumer economy, and its young demographic dividend is alluring.

Getting India to enter more trade pacts has been difficult. But on May 6, it struck a mega deal with the United Kingdom which may be indicative that India is open to trade agreements in this volatile geoeconomic environment.

A DEFENCE SHAKEDOWN

On the security front, regional countries are not holding their breath either. If Mr Trump can settle tariff negotiations with Southeast Asian countries, a proper approach would be to use the “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” strategy to get US allies and partners to uphold principles, such as freedom and navigation and no recourse to the use of force, as an implicit deterrent on China.

For now, Trump 2.0 appears to be heading in the right direction. In his first meeting with Quad leaders in January, Secretary of State Marco Rubio upheld this strategy. In his inaugural tour of Japan and the Philippines in March, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth stressed that America First does not mean America Alone.

But such a traditional US approach to regional security cannot be assured. The fear is that the US will shake down its allies and partners to carry more of the defence burden as the US cuts back on its forward-deployed posture.

No wonder, there is talk about Southeast Asian countries deepening security cooperation with Quad countries sans the US, and revived debates about South Korea and Japan breaking the taboo on nuclear weapons.

As the US-led world order frays in a multipolar one, Southeast Asian countries still retain agency to chart their own paths.

William Choong is a Senior Fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, and the Managing Editor of Fulcrum, the institute’s commentary and analysis website on Southeast Asia.

Sharon Seah is Senior Fellow and Coordinator at the ASEAN Studies Centre, ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.