Commentary: Must the process of reversing incorrect PayNow transfers be so painful?

Though Singapore’s law allows individuals to recover bank transfers made by mistake, it is more challenging in practice if the recipient does not cooperate, says SUSS law lecturer Ben Chester Cheong.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: The recent case of a man being fined for withdrawing and spending S$20,000 that was mistakenly sent to him via PayNow has sparked questions about the process for reversing erroneous payments.

It took the bank one month to unsuccessfully attempt recovery, the police two months to investigate, and the courts three years from the incident date to impose a fine on the recipient.

This drawn-out process leaves victims in limbo and enables bad actors to get away with pocketing misdirected funds, at least temporarily. While preventing such incidents through better app design should be a priority, the recovery process could use some tinkering to be simpler and faster.

HOW BANKS SHOULD MANAGE ERRONEOUS TRANSACTIONS

Under the Monetary Authority of Singapore’s E-Payments User Protection Guidelines, when an account holder reports sending money to the wrong recipient, both the sender’s and recipient’s banks are obligated to take reasonable steps to recover the funds.

This process involves tight timelines. The sender’s bank must inform the recipient’s bank within two business days, and the recipient’s bank must contact the unintended recipient and convey their response to the sender’s bank within five business days. The guidelines recognise that the timeline may be extended in complex situations.

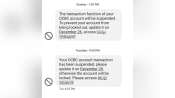

Crucially, banks must remind recipients that knowingly retaining erroneously transferred funds is a criminal offence. To enable this process, account holders must provide detailed transaction information.

The guidelines do not impose an obligation on banks to resolve mistaken payment claims. Instead, it requires banks to facilitate “effective communication between the account holder and the recipient with the aim to improve the account holder’s chance of recovering the payment”.

WHEN THINGS GET COMPLICATED

In most situations, a recipient would agree to return the wrongly credited monies. But it gets complicated when a recipient refuses to return the monies or ignore the bank’s request for information.

In such an instance, banks are typically reluctant to reverse payments and recredit the money into the sender’s account without the recipient’s consent.

This reluctance stems from two primary reasons. First, the contractual agreement between the bank and customer, as outlined in the terms and conditions, rarely grants the bank the unilateral power to debit an account without the customer’s explicit permission.

In other words, even if the sender reports the mistake, the recipient’s bank is not authorised to remove funds from the recipient’s account to rectify the error.

Second, banks would find it hard to determine whether a sender’s claim of a mistaken payment is legitimate.

From the bank’s perspective, it is nearly impossible to ascertain whether the sender genuinely made an error or if they initially transferred the money with full awareness of the circumstances. Individuals could have a change of heart after making a payment and then attempt to recover the funds by claiming it was a mistake.

Moreover, the payment could have been made to fulfil a legitimate obligation, such as settling a debt or purchasing goods. In such cases, the sender might try to retrieve the money after receiving the goods or services, putting the bank in the middle of a dispute between the parties.

PRACTICAL BARRIERS TO RECOVERING ERRONEOUS TRANSFERS

Given these complexities, banks often adopt a hands-off approach when a recipient refuses to consent to a reversal of a payment. The onus then falls on the sender to initiate legal action against the recipient to recover the mistakenly transferred funds.

Singapore law allows recovery of payments made by mistake. To recover funds, four conditions must be met: The recipient was enriched, this enrichment was at the payer’s expense, it’s unjust for the recipient to keep the money, and there are no valid defences.

In practice, recovering mistaken bank transfers in Singapore is often more challenging than the law might suggest. Without the recipient’s cooperation, the sender might need to go to court. This can be time-consuming and expensive, especially for smaller amounts.

Most people need legal advice to navigate the system, significantly increasing costs. The costs involved can outweigh the mistaken payment amount. Even if the sender wins, the recipient might not have the means to repay, rendering such a victory pointless.

There is a need for more accessible, cost-effective methods to resolve such disputes, regardless of the sum involved or the individual’s financial standing.

WHAT MORE CAN BE DONE?

One solution would be to empower banks to mediate and resolve more of these situations directly through legislation.

For instance, in the UK, if the recipient disputes the claim or does not respond to the sender’s bank, the receiving bank will freeze an amount equal to the mistaken payment until the matter is resolved.

Singapore banks could be granted authority to temporarily freeze recipient funds, investigate the claim by checking sender and recipient transaction histories and contacting both parties, and then reverse the transaction if an honest mistake seems likely.

If such a process is implemented in Singapore, safeguards and limits would be critical. Senders should have to attest to the mistake and face penalties for false claims.

Dollar and time limits on bank reversals would be needed to prevent abuse and protect recipients’ access to their money. Large, suspicious transfers would still require police involvement. But most incidents involve modest sums inadvertently sent to the wrong person, where a faster resolution by the bank could suffice.

An alternative is to expand the Small Claims Tribunal’s jurisdiction to include unjust enrichment claims for mistaken payments, which was suggested by MP Murali Pillai (PAP-Bukit Batok) in a 2022 parliamentary question.

This would allow mistaken transfers of sums not exceeding S$20,000 to be reclaimed through a streamlined, user-friendly process. No lawyers needed, minimal fees and a quick resolution.

Empowering the Small Claims Tribunal to handle these cases could ensure that the right to recover mistaken payments is not just a legal theory, but a practical reality for all in Singapore. It could provide a cost-effective and quicker method to recover misdirected funds.

Ben Chester Cheong is Law Lecturer and inaugural START Scholar at the Singapore University of Social Sciences, and Lawyer at RHTLaw Asia LLP.