Commentary: PM Lee's deepfake video and the risk when seeing is no longer believing

Our ability to discern between real and fake has never been more challenged as deepfakes become mainstream in the online information space, says S Rajaratnam School of International Studies’ Dymples Leong.

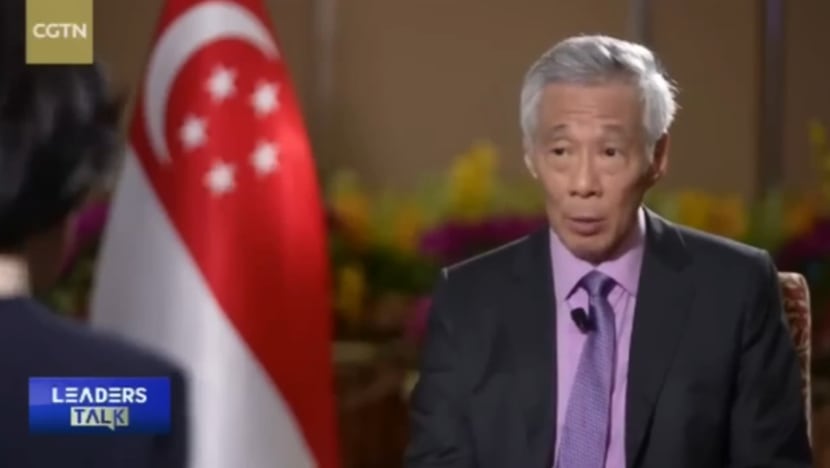

A screengrab from a deepfake video of Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong promoting an investment scam.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: Would you trust a video circulating online of Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong seemingly advocating a cryptocurrency scheme with guaranteed returns on investment? Or videos of CNA news presenters reporting that other public figures have endorsed similar sure-fire ways of making money?

A recent deepfake video of Mr Lee, which appeared to be altered from an interview in March 2023 with Chinese news network CGTN, has sparked concerns about the risks of artificial intelligence (AI) generated videos.

Deepfakes are synthetically generated or manipulated by a type of AI known as deep learning, and can consist of videos, images and audio. Techniques such as face swapping and lip synching allow for switching a person’s likeness or altering voices of individuals.

Advances in generative AI technology has now made deepfake generation easier. Commercial apps and tools allow deepfakes to be generated quickly. Technological improvements have also refined and reduced overt signs of synthetic manipulation.

Some deepfakes, like the one of Mr Lee, can be obvious to the more discerning: It’s hard to believe that the Prime Minister would plug dodgy investment opportunities. But the worry is always that such technology would be used for more malicious purposes, such as cybercrime and disinformation.

What happens if, instead of an interview, the manipulated video was of parliament and about issues of import to Singapore?

POLITICIANS, BUSINESSMEN AND JOURNALISTS ARE PRIME TARGETS

As deepfakes are trained on large datasets, public figures such as politicians, businessmen and journalists are prime targets, given the wealth of images and footage available.

Cybercriminals have already adopted deepfakes in their toolbox. Victims of investment scams falling for deepfake videos in Asia have been on the rise while deepfake audio mimicking voices of CEOs have been used to defraud companies. A video of Indian billionaire and businessman Mukesh Ambani was manipulated with a fake voice-over to promote scam investment opportunities.

More worryingly, deepfakes have been used to spread disinformation, to mislead towards malicious ends. In March 2022, in the early days of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a low-quality deepfake video of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy urged Ukrainians to surrender.

A deepfake of United States President Joe Biden appearing to announce military conscription in the context of the Israel-Hamas war was widely disseminated in the days after the conflict started. Video footage from a 2021 speech by Mr Biden on insulin prices was adapted and altered with the addition of manipulated audio.

In Slovakia, a deepfake audio released just two days before the 2023 Slovakian election contained alleged voices of a politician and a journalist discussing election rigging. The fake video displayed signs of AI manipulation, but it was still widely shared on Instagram and Telegram.

Influence campaigns have also utilised deepfake technology. An investigation in 2019 by Meta revealed a coordinated inauthentic network of Facebook accounts that utilised AI-generated profile photos to create fake personas.

DISINFORMATION IN A HISTORIC ELECTION YEAR

With two ongoing wars and at least 40 countries and territories going to the polls in a historic election year, the dangers of maliciously manipulated content, especially in wartime and election campaigns, cannot be understated.

Allegations of electoral interference have surfaced. Taiwan’s president-elect William Lai Ching-te had, in the run-up to the election on Saturday (Jan 13), accused China of disinformation campaigns and interference.

The weaponisation of deepfakes for disinformation has the potential to be a destabilising effect on society, by significantly influencing public opinions, perceptions and even actions.

Deepfakes could be deployed during elections where videos could be microtargeted towards specific communities or demographics with intent to inflame tensions. It could be used to disseminate misleading or deceptive messaging about electoral processes in attempts to diminish public trust in electoral integrity.

This could potentially lead to a public that has diminished trust and credibility in public media sources and news. Malicious deepfakes stir up insecurity and distrust, amplifying information contrary to fact. It could undermine the legitimacy of public institutions and processes.

Authentic videos could run the risk of being dismissed as fake to damage the reputation of individuals or to discredit a political opponent. It has also led to concerns of whether the public would hesitate to engage with deepfakes in general or be apathetic towards AI-generated content.

SEEING IS NO LONGER BELIEVING

Both information and media literacy are crucial. Public education efforts can help in highlighting the signs of AI manipulation in deepfake videos, such as identifying if the lip sync of the video is unnatural or does not resemble the voice of the target person.

But the erosion of trust in our abilities to discern between real or fake has never been more challenged, as deepfakes become mainstreamed in the online information space.

Even those prepared to fact-check run the risk of checking against existing misinformation. Trusted and verified sources of information have never been more important.

Malicious actors will continue to seek and exploit loopholes in the policies of social media platforms. Social media companies can help to refine their policies to plug in the gaps to deter potential abuse.

Authorities globally have introduced legislation for deepfake videos. The European Union recently passed the EU AI Act, requiring AI-generated videos to be watermarked. Singapore in January 2024 also announced an initiative to explore deepfake detection tools and technologies.

Advances in deepfake technology are expected to keep coming. We need to be armed with the vigilance and knowledge against malicious intentions, when so much of our lives are online. The next deepfake video we come across may not be so easy to spot.

Dymples Leong is an Associate Research Fellow with the Centre of Excellence for National Security (CENS) at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.