3 reasons to watch CNA’s 3-part series on dying alone in Singapore

Dying alone is an increasingly grim reality in Singapore. CNA’s latest trilogy delves into the identities of elderly individuals in danger of suffering this fate, the factors contributing to their solitude and ongoing efforts to support them.

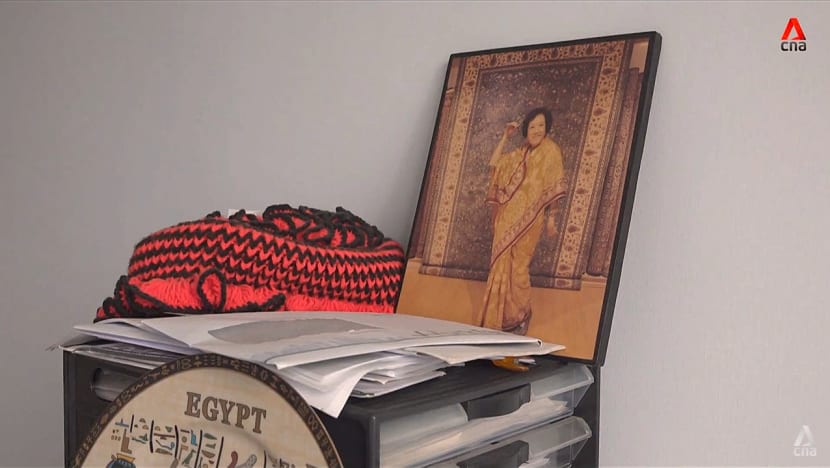

Volunteers with Cheng Hong Welfare Service Society sending a deceased person off, when there was no one else to do so.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: Since he moved to his one-room flat years ago, Heng Aik Min has never closed the door — only the metal gate — when he is at home.

This is so that he can be found quickly if he dies inside.

A CT scan in 2017 showed issues with his gall bladder, cysts on his liver and stage-three kidney cancer, on top of his high blood pressure. More recently, he developed a tumour in his thyroid that could turn malignant anytime.

“If that happens, I’d have only three months to live,” the 65-year-old said matter-of-factly.

Heng, who has lived alone since his divorce, is “not the least bit afraid of death”. But he added: “I’m just afraid of being a decomposing corpse without anyone clearing my body.”

His concerns are not unfounded. Last year, the media reported at least 37 cases of lonely deaths in Singapore — individuals who died without any suspicion of foul play and whose bodies were discovered only after a period of time.

Experts believe more cases remain unreported. For instance, when Bobby Tan’s aunt, 77, died in her home, it was days later when her neighbours, alerted by an unusual odour, called the police. By then, her body had begun decomposing on her sofa.

Heng and Tan’s aunt are only two of the many elderly individuals who live or have lived in solitude.

The population of residents aged 65 and over in resident households has nearly doubled, from 389,800 in 2012 to 683,800 in 2022. Of these, the percentage of those living alone has risen from 8 per cent to 11.5 per cent during that period.

Who are the people who fade away unnoticed and alone? What follows in the aftermath of these lonely deaths?

CNA’s new series, Dead Alone In Singapore, explores the nuanced truths of dying alone from the perspectives of those at risk and those who witness these poignant events. Here are three reasons to watch it.

WATCH PART 1: Living and dying alone in Singapore — Facing lonely deaths (45:41)

1. MEET THE FOLKS WHO FIND THEMSELVES ALONE

Not all individuals who die alone are truly isolated. Heng, for example, has three children in their 30s and 40s, while Tan’s late aunt and her sister phoned each other occasionally.

According to National University of Singapore (NUS) associate professor of social work Corrine Ghoh, 11 out of 13 cases of lonely deaths between this January and April were known to a neighbour, friend, next of kin or a social service agency.

"Whether you have a family or not isn’t the point,” Heng told CNA. “If they weren’t coming over to see you, it’s the same end result.”

Some people, however, choose to live in solitude. Heng sometimes wonders if he is anti-social, preferring to withdraw from family interactions, while Tan’s aunt, according to him, “kept to herself”.

Others find themselves alone not by choice. Studies focusing on older adults, typically aged 60 and over, show that those living by themselves often contend with elevated levels of depression and heightened risk of mortality.

One in three residents aged 60 and over felt somewhat or mostly lonely, found a 2019 study by the Duke-NUS Medical School’s Centre for Ageing Research and Education.

Loi Pak Lin, 81, is now one of them, following her husband’s passing six years ago, her elder brother's recent death and her younger brother’s stroke, which left him stricken with health problems.

“It’s very lonely, very devastating,” she lamented. “To die alone without anyone knowing, isn't that heartbreaking?”

Besides the sorrow of dying alone lies the tragedy of departing without dignity. “I don’t want to cause a stink and make people fed up,” Heng said. “I’d be offending people even after death.”

He has another vision for his final departure. As a volunteer and member of Cheng Hong Welfare Service Society, which runs a free afterlife memorial service (AMS), he attends the cremations of other lonely individuals to bid them a respectful farewell.

Its volunteers bow, burn incense and wish the departed a peaceful journey. “We don’t want to let other people treat them like rubbish,” he said. “I want to be sent off this way.”

2. MEET THE STRANGERS CARING FOR THE LONELY

When death is quiet, there are people who answer its whisper — people like Linda Tan. As an eldercare programme executive with Cheng Hong, she helps seniors with no next of kin prepare for their last rites.

Sometimes these send-offs can be emotionally challenging for her, especially after she has got to know the seniors.

When Ho Soo Wah died, it was a bittersweet moment for her. Originally from China and old enough to be her great-grandfather, the 96-year-old was her first AMS applicant — and one of the earliest volunteers in the Singapore Armed Forces.

WATCH PART 2: What happens after someone dies alone? (45:22)

When she collected his body, two weeks after he died, it had started to decompose, which made the skin particularly fragile to the touch.

“I did buy a set of clothes, … knowing that he’d (gone to) A & E (without) a proper outfit,” she said. “It’s a bit sad (that I couldn’t dress him).”

Cheng Hong used to handle a lonely death every two to four days but now has a new case every one to two days and sometimes multiple cases in a day, said founder Lim Hang Chung.

The surge in cases is also felt by funeral parlours that take up cases from organisations like Cheng Hong.

Despite over a decade of experience handling bodies, Affinity Funeral Services funeral director Jack Lee still finds lonely deaths particularly heart-rending. “It’s not just death itself that’s scary,” the 26-year-old remarked. “It’s living (out) your life being alone.”

Using his company’s TikTok account, he creates videos about lonely deaths to raise awareness among the younger generation.

Rahman Razali, 42, co-founder of cleaning firm DDQ Services, employs a similar approach to advocate for lonely elderly folk. As a professional trauma cleaner, he has encountered many cases over the years.

One of his TikTok videos, which garnered over 1.6 million views, was about an elderly man who died one or two days before Hari Raya. A baju kurong was hanging in a corner of the man’s room, ready for the celebration before death intervened.

“When we went over, … the whole bedroom was flooded with water,” Rahman described. “The mattress (was) soaked ... with the bodily fluids, and (there were) maggots.”

He hopes that through his videos, more people will reach out to these elderly folk and help “keep an eye on them”.

WATCH PART 3: Can we prevent lonely deaths in Singapore? (45:11)

3. SEE THE PROCESS OF HANDLING LONELY DEATHS

Some of the elderly whose homes Rahman has cleaned had died in their sleep; most of the others had had a fall, he said. Either way, there is one unmistakable sign of a neglected death.

“The smell, I’d say, is a mix of rotten eggs (and a) fishy smell, then … this very fruity undertone,” he described. When this odour reaches neighbouring homes, it often prompts calls to the police.

What follows is the removal of the body and the involvement of a claimant — if not the next of kin, then a friend or a volunteer like Linda Tan — along with the clean-up crew.

Rahman’s team begins with a pre-inspection, noting the extent of contamination to plan their cleaning approach. This sometimes involves the lifting of furniture and other items to ensure thorough cleaning of the affected area.

WATCH THE DIGITAL EXTRA: Don’t let me die solo — How can we prevent lonely deaths? (10:28)

“We wouldn’t be able to see the body physically, but we’d definitely see the remains … the body fluids, the hair, the nails, the skin,” he said.

Following meticulous sanitation, the deceased person’s belongings are returned and sorted by the claimant, who may then proceed with funeral arrangements.

Rahman has seen the number of cases increase since 2018. And that does not seem likely to change soon, thinks Ghoh. “This is an emerging phenomenon now,” she said. “I don’t think it’s going to go away.”

Watch all three episodes of Dead Alone In Singapore here: Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3.

Editor’s note: In the original article, the proportion of elderly residents living alone was based on households with reference persons aged 65 and over. Following a clarification by the Department of Statistics, the percentages have been amended to reflect a broader base of households with elderly residents.