This polygraph examiner can sniff out lies, with or without equipment. Here’s how he does it

Malaravan Ponniah has done lie detector tests on rape suspects, cheating spouses and even job applicants for high-level positions. He tells CNA Insider’s Heavy Duty podcast what is fascinating about reading people.

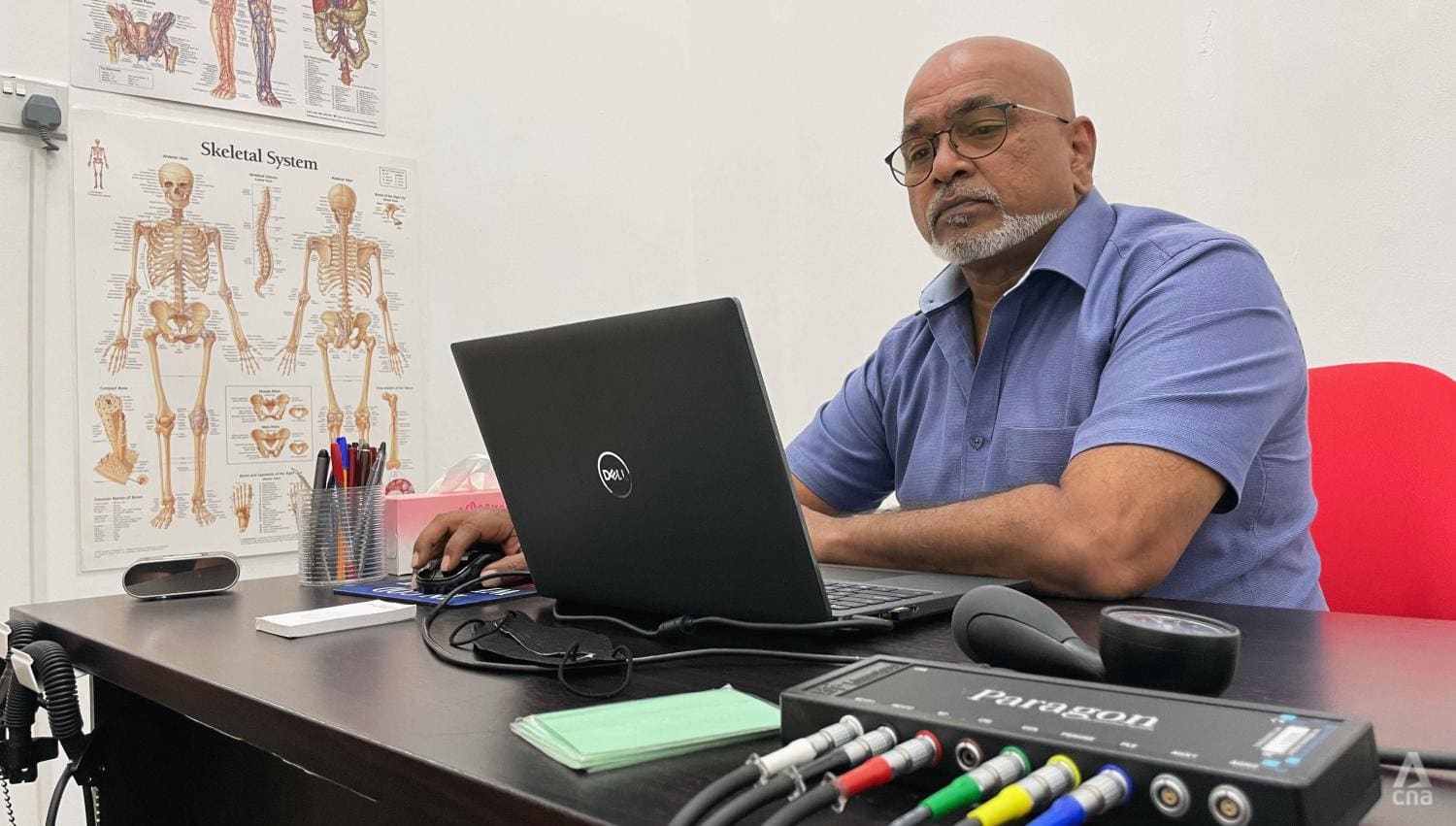

Malaravan Ponniah, or Ron, was in the military for 32 years. (Photo: Eileen Chew/CNA)

SINGAPORE: A sign marks the entrance to a room in security firm SecuriState’s office. It says: “In God we trust. All others, we polygraph.”

Many alleged molesters, drug offenders and love rats have entered this room with trepidation. It is where they are strapped to equipment and their breathing, sweating and blood pressure come under Malaravan Ponniah’s scrutiny.

They are people who have opted to undergo a polygraph or lie detector test, with Malaravan — or Ron, a moniker from his military days — as their examiner.

They may be clients taking a polygraph exam to vindicate themselves. One man, for instance, wanted to prove to his father-in-law that he did not hit his wife. (She made it up to get a divorce because she was having an affair).

Or they may be people under investigation whose lawyers have sent them to Ron before they decide whether to submit to a polygraph conducted by the police.

Listen to the professional lie detector:

Whatever the case might be, most people get nervous when they step into his exam room.

“I’ll ask them to close their eyes and relax for a while … and I’ll check whether their readings are stable,” said Ron, 60, the managing director of SecuriState and one of a handful of commercial polygraph examiners in Singapore.

And then the test begins.

THE ‘X-RAY GUY’

While polygraph exams cannot be used as evidence in Singaporean courts, they are widely used by law enforcement agencies here and round the world. In cases lacking evidence, polygraphs can aid law enforcers in decision-making. “It facilitates investigation,” said Ron.

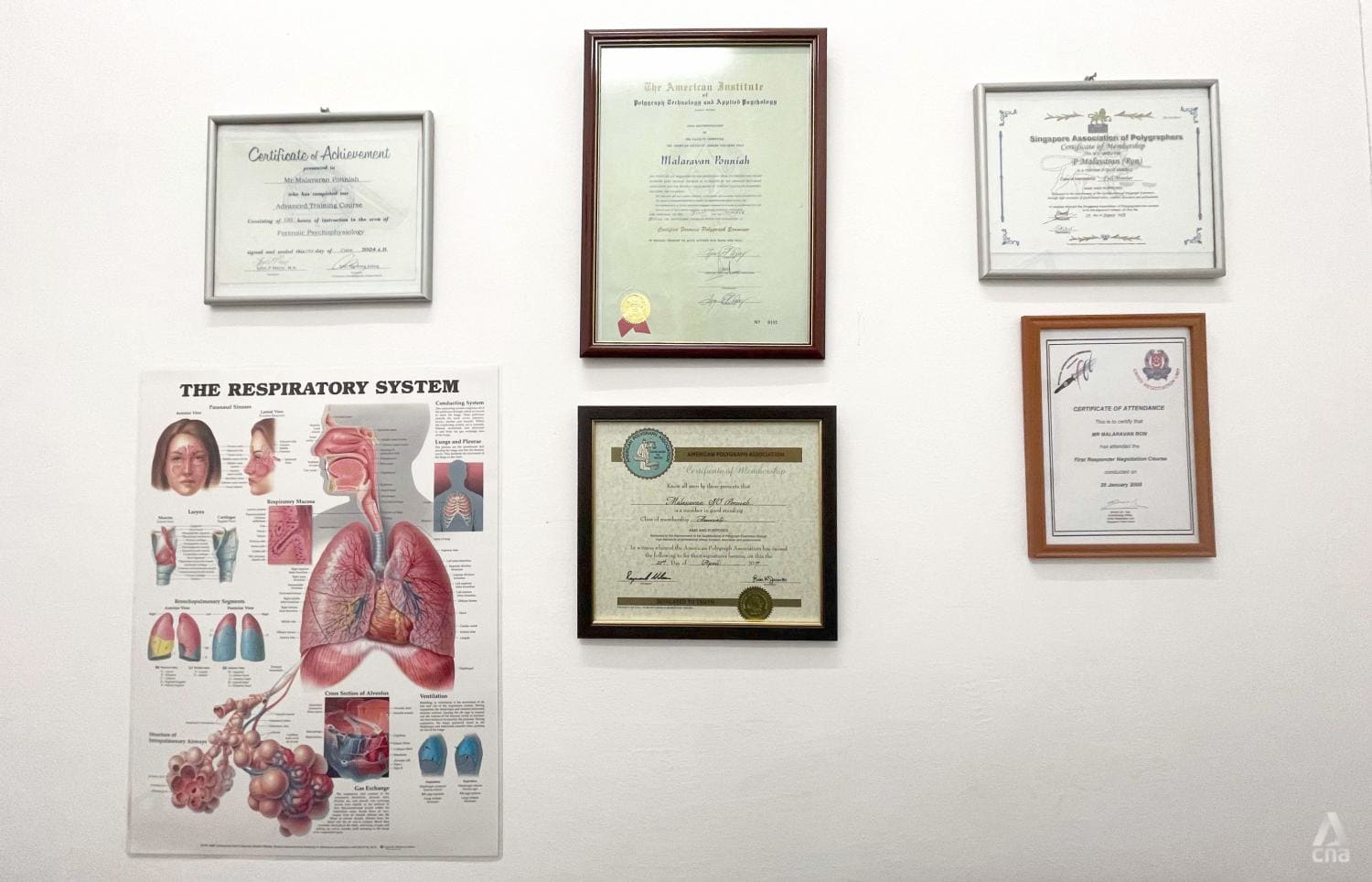

He was trained as a forensic polygraph examiner during his 32-year military career when he was selected to attend a three-month course in the mid-1990s.

It was taught by United States instructors and covered physiology, psychology, instrumentation and interview techniques, he said.

Participants had to undergo a polygraph test where they were asked about any previous drug activity, criminal record and other areas of their past. This was to see if they were suitable for the course.

And to pass, each student had to conduct three exams in real-life cases. Ron remains proud of the fact that in one of the exams, he secured a confession from a rape suspect.

“It was after the test. When I looked at the charts, I realised he wasn’t telling the truth,” recounted Ron, who switched off the equipment and persuaded him to come clean about it.

“For example, you’ll tell them, ‘I know you never planned to do it, but it just happened, and you lost control of yourself. That’s what happened, correct?’”

After reflecting and coming to terms with their actions, the subjects sometimes unload the truth, said Ron, who believes that to err is human.

Sometimes, situationally, you may make a mistake … big or small. If you admit to it and get it sorted out, you’ll be a better person. That’s my take.”

That said, he has met his share of hard-core suspects who — whatever the test results — listen to interviewers without emotion and then reply, “Okay, any other questions? Can I go?”

“You can’t break them,” he said.

Contrary to what some may think, there are no spontaneous questions or surprises during a polygraph exam. Ron does a pre-test interview lasting 30 to 40 minutes with the client, to go through the facts of the case and formulate his test questions.

There is no need for mind games, he said. “You just need the facts of the issue … ask them to narrate the story — what happened — (and) don’t let them (give you the) runaround.

“And then I’d follow with the questions. If I need more clarity, then I dig more into that particular answer.”

The pre-test interview also allows him to read a person and get a sense of whether he or she may be telling the truth.

Ron honed his people-reading skills through “patience and practice”. In the early days, he watched soap operas on mute to pick up the “behavioural attributes of actors”. “From Korean to Indian to English (soap operas) — just about anything,” he cited.

There is no fixed telltale sign that someone is lying, he said. It is a cluster of behavioural attributes, such as breaking eye contact, facial expressions, straying from the storyline and attempts to buy time.

“If you’re meeting a person for the first time, and you just engage in a normal conversation for about 10 to 15 minutes, you won’t be able to differentiate whether the person’s telling the truth or not. It takes some time,” he said.

He does not make any conclusions until after the polygraph exam. The charts showing a person’s breathing, skin conductivity (sweating) and blood pressure “won’t lie” because “everything’s attached to the examinee’s body”.

“I’m just interpreting the reactions to the questions,” said Ron, who described himself as “an X-ray department guy”. “Data interpretation is what we examiners do.”

CUTTING LOOSE FROM WORK

Ron began offering commercial polygraph services in 2012, a year after he retired from the army. He estimates that there might be four people here from three companies offering commercial polygraph services.

These days, about 60 per cent of his cases involve cheating spouses. The rest come from law firms and from employers doing pre-employment checks.

Couples usually go to him when both partners have suspicions or when one partner wants to prove something to the other, he said.

As for pre-employment exams, clients are usually hiring people for cybersecurity, finance or management-level positions, he cited. For instance, firms may want to check to see if a potential employee has ever mishandled funds or manipulated data.

WATCH: Meet the polygraph expert: I’m a human lie detector (7:06)

Studies put the accuracy of polygraph exams at 80 to 90 per cent of the time, and Ron acknowledges that “there’s a small chance of error”. But this is akin to the chances of a successful surgery, he reckoned. “There’s no perfect result for everything.”

To do his job professionally, he does not track the outcomes of cases he has tested. He does not scan the news when a case he has tested makes it to court, for instance.

“I know examiners who do that, especially the nosy ones. But I think to be professional, you shouldn’t have attachments to the cases. Once you finish your job — you’re professional, your report is accurate, your findings are good — cut loose (from it),” he said.

“The rest is in the hands of the police or law firms or the individual family.”

It was not always so easy, however, to switch off from work. Ron said he took “quite a bit of time” to become less judgemental about people over simple matters.

It could be a friend backing out of a gathering by citing “something to sort out” at home. “But you don’t believe him,” said Ron. “It took some time to take at face value what a person says.”

His younger son, P M Gauthaman, can offer a trove of stories about growing up with a father who could sniff out lies. The 27-year-old recalled making meticulous plans and being on his toes as a child to avoid getting caught — like when using his father’s computer to watch cartoons.

“I (wasn’t) allowed to use the computer to play games or watch cartoons until he was back from work,” said Gauthaman. “He had good intentions, because I was really lazy, and it was his way of keeping me on track.”

But Gauthaman duplicated the key for the room where the computer was kept. He was careful to leave no digital trace. He even placed a tripwire toy at the lift outside their flat so he could get a signal on the control kit when someone walked out of the lift.

“That’s when I’d just bolt out (of the room), shut the computer down. Mind you, I was nine years old,” he recounted with a laugh.

Somehow, (my father) knows. I leave no traces except for my face and my reaction when I talk to him.

“He’s the kind of guy who’ll nod his head and smile. And then … I’ll think I’m scot-free, and all’s good. At the end, that’s when he (lets on that he) knew all along.”

Gauthaman is now SecuriState’s head of systems and technology. He oversees a new division in the company that deploys remotely operated vehicles, or underwater drones, to inspect structures underwater.

His father is someone who “listens more than he speaks”, said Gauthaman, who remembers asking him why he was so quiet with friends or potential clients. The reply? It was to observe people and “read the room”.

“Definitely, I’ve learnt to talk less and listen more,” said Gauthaman, who described his father as strict but caring.

He has also long since given up trying to lie to his father — as have some of Ron’s friends.

“They’ve told me right to my face, ‘I don’t want to lie, I better tell you the truth,’” said Ron. “I say, ‘Yah, good.’”

To hear about the polygraph test the writer took, as well as memorable cases in Ron’s career, tune in to Heavy Duty by CNA Insider.