74 of the world’s 100 most polluted cities are in India. Can the country clear its bad air?

Millions of lives in India have been lost because of air pollution. The programme Insight looks at how a growing middle class and geography play a part in the country’s struggles and how recent efforts stack up.

A child receiving respiratory treatment at the Hakeem Abdul Hameed Centenary Hospital in Delhi.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

NEW DELHI: At the age of four months, Anvi landed in intensive care. Her parents had rushed her to hospital on the advice of a clinic doctor who noticed her chest pain upon examination.

She was not the only infant in the ward, which was filled with the coughs and cries of other children, including older ones, struggling to breathe.

The culprit? The thick smog choking India’s capital territory.

“Delhi’s pollution is very bad. We’re older, and it isn’t affecting us as much,” said Anvi’s father, Amrit. “But my daughter is four months old. Her immune system is very weak. It’s very difficult for her.”

Delhi now has the dubious honour of being the world’s most polluted capital or capital territory for six consecutive years, according to the annual World Air Quality Report by Swiss air quality monitoring firm IQAir.

In November, the city’s Air Quality Index (AQI) soared to 795, almost eight times the threshold value of 100, when air quality becomes unhealthy. In some areas, the AQI even reached 1,185.

But the pollution is not confined to Delhi. Six of the world’s 10 most polluted cities last year — and 74 of the 100 most polluted cities — were in India, according to IQAir.

A report released last year by the US-based Health Effects Institute, in partnership with UNICEF, also found that air pollution caused 2.1 million deaths in India in 2021. This included 169,400 children aged under five — the highest number globally.

“Pollution and the health risk are now quite uniformly spread (across India),” said Anumita Roychowdhury, the executive director of research and advocacy at the Centre for Science and Environment.

WATCH: India has 8 out of 10 most polluted cities in the world. Why? Can it beat air pollution? (46:51)

Yet, pollution is hardly a political issue in the country, and living with polluted air has become nothing more than the norm for many locals.

“I’m not wearing a mask because I find it a little inconvenient, and I probably have got used to the pollution,” said New Delhi resident Meera Bhatia, when the AQI was between 200 and 400 (very unhealthy to hazardous). “Ignorance is bliss sometimes.”

Even as the lack of a political push by the people is an obstacle to change, experts warn that the crisis can no longer be ignored as the deaths and economic toll mount.

The programme Insight examines why India struggles with air pollution, why the smog is worse in Delhi and during winter and what it will take to combat the problem.

WHY DELHI SUFFOCATES, ESPECIALLY IN WINTER

Delhi, the world’s second-most populous capital territory, is at the heart of India’s air quality problem because of its countless sources of pollution: industrial activity, construction dust, waste burning and, above all, traffic.

Nearly 656,700 new vehicles were sold in Delhi in 2023; in addition, around 1.1 million vehicles enter and exit the city daily. Car ownership is being driven by India’s growing middle class — and is often the most practical choice in Delhi.

“You’re making flyovers, widening roads that are impossible to cross,” said Roychowdhury.

“The road design is telling us ... we’re designing the city for you to drive a car, but not to walk, not to cycle and (not to) use public transport.”

While Delhi has imposed measures to cut emissions, such as stricter emission norms, clean fuel mandates and electric vehicle incentives, enforcement remains weak. Many of the city’s eight million registered vehicles (as at 2023) are old, with polluting models still plying the roads.

Adding to its burden is pollution from areas outside the city. This accounts for more than half of Delhi’s smog, according to the Centre for Science and Environment, and includes crop burning.

“Farmers find it easier to just burn (their crop residue),” said Roychowdhury. “It’s much more expensive to hire labourers to cut it from the roots.”

Despite regulations and fines to discourage crop burning, and despite some incentives for farmers to harvest their crop residue to sell as straw instead, the practice continues.

While the incidence of crop fires in states like Punjab and Haryana has largely fallen in recent years, some other states have seen more frequent incidents, and the smog wafting into Delhi remains significant.

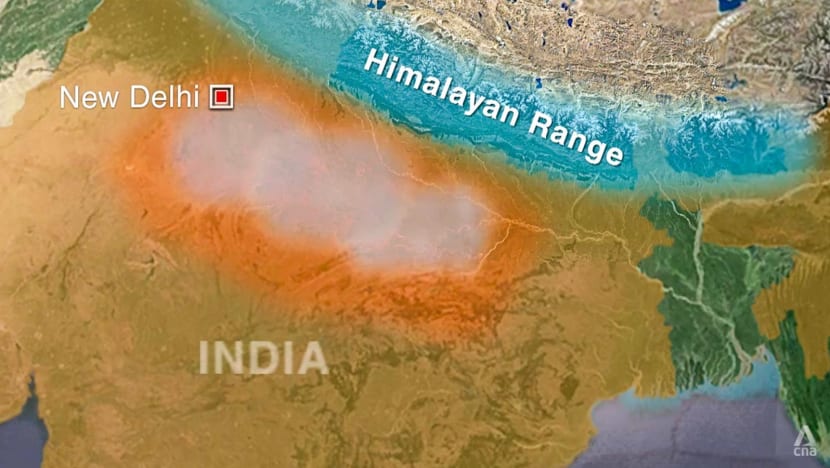

Delhi’s geographical location is also not in its favour. The landlocked city sits on the Indo-Gangetic Plain, a low-lying region stretching to the foothills of the Himalayas, which act as a wall, trapping polluted air.

“(Delhi) can swallow everything but can’t (expel) anything,” said Gufran Beig, chair professor at the National Institute of Advanced Studies.

According to experts, geographical location and weather patterns play a big part in India’s seasonal spike in pollution. Hence coastal cities see relatively better air quality compared with inland areas in northern India, such as Delhi.

In summer, warm air near the ground expands and rises, causing denser, cooler air from the Himalayas to rush into the space, creating wind that scatters the smog.

But in winter, cold ground-level air does not rise and disperse pollutants. The result: a blanket of toxic air that lingers for days, even weeks.

To be sure, air pollution remains a problem “throughout the year” and across India, said Zerin Osho, the director of the India programme at the Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development.

“The entire country is grappling with this,” she said. “It just becomes more prominent … during the winters.”

“A SILENT KILLER”

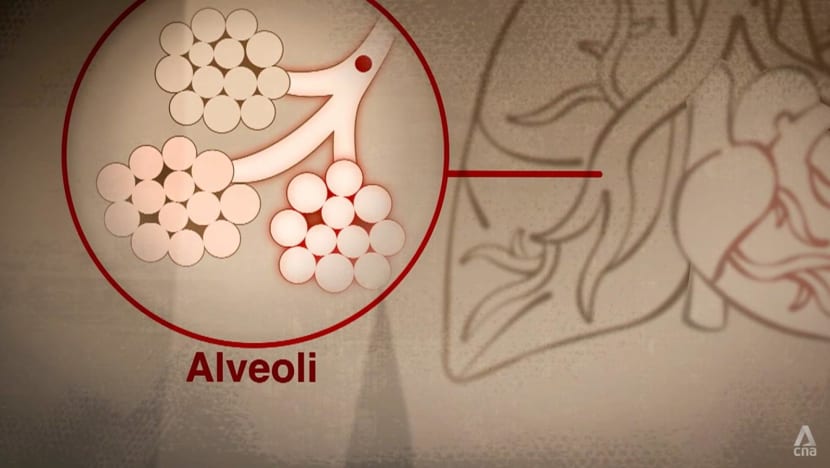

When experts talk about poor air quality, they are most concerned about particulate matter 2.5, also known as PM2.5. These microscopic particles measure 2.5 microns or less in diameter — roughly 30 times smaller than the width of a human hair.

They can be found in pollutants such as dust, smoke and soot, or black carbon, and have been linked to respiratory and heart diseases as well as cancer.

“(They) will get deposited … (in) your lungs,” warned Beig. “They’re the most lethal particles.”

The particles are so tiny they can stay in the air for long periods, according to IQAir. Once inhaled, they can lodge in the respiratory tract, irritate its lining and damage the lungs.

“PM2.5 particulate material is so small that it can go through the blood from the mother to the foetus,” said Neelam Kler, adviser to the neonatology department at Sir Ganga Ram Hospital in New Delhi.

Her team found that PM2.5 pollution can “significantly” affect foetal weight and may increase the risk of underdeveloped lungs, among other health issues.

According to the State of Global Air 2020 report, more than 116,000 newborns in India died in 2019 within 27 days of birth as a result of air pollution exposure — again the highest number globally, averaging 318 deaths a day.

“The cost of air pollution isn’t that it kills directly, but it worsens the underlying condition, tilts the balance towards more severe disease and causes death,” said Randeep Guleria, chairman of Medanta’s Institute of Internal Medicine, Respiratory and Sleep Medicine.

Air pollution currently is what I call a medical emergency, and it’s a silent killer.”

Beyond the human cost, there are the economic drawbacks.

Global consulting firm Dalberg concluded in 2021 that air pollution cost India US$95 billion annually from lower labour productivity and consumer footfall and premature death, which amounted to 3 per cent of the country’s 2019 gross domestic product.

“If I’m a company investing in India, and I know that my labour isn’t going to be able to show up to work, it’s a net loss for me,” said Osho.

Arunabha Ghosh, chief executive officer of the Council on Energy, Environment and Water, added: “We want to be an open economy. We want to attract foreign investment. Clearly, we must be losing foreign investment with polluted cities.

“The day we recognise that in the world’s fastest-growing major economy, air pollution is holding us back from growing faster, … we’ll realise that investing in clean air is one of the best investments we can make for our economic development.”

GAPS IN IMPLEMENTATION

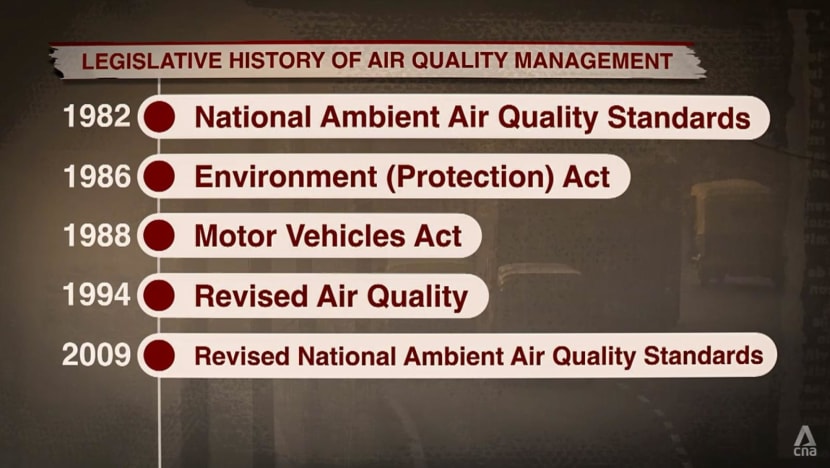

India has been confronting its pollution problem for some time — since the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act was passed in 1981 — but results have been mixed. Experts have pointed out gaps between policy aims and implementation.

In 2019, the government launched the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP), for which more than US$2.3 billion has been earmarked until 2026, to cut air pollution levels in 131 cities across India.

In Delhi, two smog towers were installed in 2021 to function as air purifiers, sucking in the surrounding air and filtering out particulates.

The building cost was roughly 200 million rupees each (US$2.4 million), with monthly operational costs of 1.5 million rupees each by their second year.

But with the data showing that the towers lowered pollution by only 17 per cent within a 100m radius, more than 47,000 towers would be needed to cover the whole city, which the Delhi Pollution Control Committee said was impractical.

Even if at least 500 to 600 towers are needed, Osho cited conservatively, “when you do a cost-benefit analysis, it doesn’t make sense”.

Another criticism from experts is that the government’s monitoring and clean-up efforts are targeting the wrong pollutants.

For example, during months with the poorest air quality, sprinklers in Delhi are deployed to trap construction dust, which comprises mostly PM10 particles.

“(The authorities) do really well on dust parameters but not necessarily on the lethal parameters. So they started focusing on dust,” said Osho, who cited data showing that 67 per cent of NCAP funding was spent on dust reduction.

“But the one that gives you lung cancer, PM2.5, isn’t being looked at (enough).”

According to her, India’s Central Pollution Control Board has the idea that “if you’re reducing PM10, which is a bigger molecule, you’re automatically reducing PM2.5” — which, she said, “doesn’t hold, mathematically”.

“To explain this very simply, if you wear a cloth mask, you’ll be able to protect yourself from dust because it’s PM10. But PM2.5 … will pass through a cloth mask,” she continued.

“If you’re only reducing PM10 and not PM2.5, you’re still going to die.”

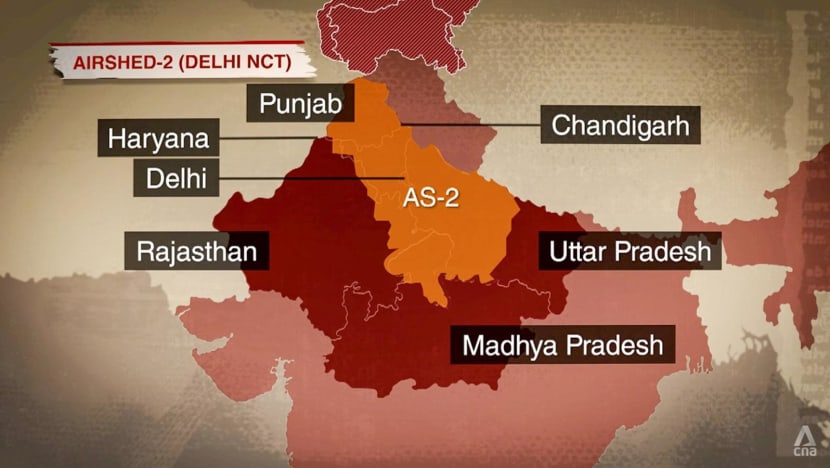

Besides a greater focus on tackling PM2.5 particles, experts are calling for a shift from a city-centric approach to an airshed-centric approach, as air pollutants are not confined by state or city boundaries.

An airshed refers to a geographic area sharing the same air quality and movement conditions. In India, this area could span several states.

So in 2021, the Commission for Air Quality Management in National Capital Region and Adjoining Areas was set up to coordinate efforts across territories.

But when the air quality worsened last September, the Supreme Court chastised the commission for failing to enforce its own directives and prosecute any stubble-burning violations.

“It’s a multidisciplinary, multi-stakeholder kind of an issue,” said the commission’s member-secretary, Arvind Nautiyal. “Getting all those people together will be an onerous task. It’s definitely a long journey.”

TO MOVE OR NOT TO MOVE?

While progress on the issue creeps along, locals in Delhi and the rest of India may have choices to make.

Madhu, a writer who moved from Chennai for a job in Delhi in late 2023, found the capital territory’s air so debilitating she decided to leave last year.

“I didn’t have an option to go out a lot without coming back with a cold or a cough or a dizzy head,” she said. “When my health just kept deteriorating, … I realised that it’s probably not (all) worth it.”

While she had the means to move, millions of others do not.

Some of Delhi’s poorest people, for example, live and work in or around the city’s three landfills, where waste picking is often their only source of income. These mountains of trash regularly catch fire, releasing plumes of noxious smoke.

“There’s a lot of smoke in the summer,” said Muskan, whose family survives on picking and selling waste. “It even stings the eyes.”

Even efforts to manage waste through incineration at waste-to-energy plants add to the pollution. With the landfill fires and winter smog, the urban poor in Delhi are left exposed to the elements.

Back in Anvi’s ward, a toddler named Humaira lay limply in her mother’s arms. She had been admitted with a bad cough and cold and breathlessness.

“We want to leave (Delhi), but we don’t have a job,” said her father, Arif. “There’s nothing.”

There is no escape in many parts of the country.

According to the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago’s latest Air Quality Life Index report, 42.6 per cent of India’s population in 2022 lived in areas that did not meet the national air quality standard for PM2.5.

“Pollution is concerning,” remarked a Delhi University student who gave his name as Harshanshu. “(But) with problems like food, clothes and houses not being solved, the people of the country will think about pollution later.”

This goes to the “core of the issue”, which citizens “haven’t internalised”, observed Ghosh.

“We still need a democratic demand for clean air,” he said. “Bad air isn’t something that you become immune to — this isn’t a virus. … This is a toxin.”

Watch this episode of Insight here. The programme airs on Thursdays at 9pm.