As Myanmar military rule drags on, son of ousted former leader Aung San Suu Kyi pleads for her freedom

He told CNA that he hopes Myanmar’s military regime would free his mother and other political prisoners, and return the country to its democratically elected government.

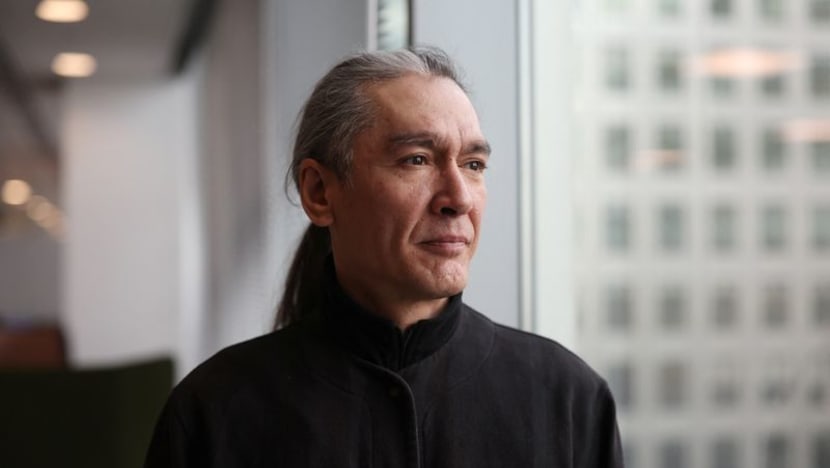

Kim Aris, the son of Aung San Suu Kyi, Myanmar's detained former leader, poses for a portrait at the Reuters office in London, Britain, April 18, 2024. (FILE PHOTO: REUTERS/Suzanne Plunkett)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

It has been a year since the son of deposed former Myanmar leader Aung San Suu Kyi received a handwritten letter from his mother, the only contact he has had with her since she was detained.

“She couldn't say a great deal in that letter, since we know that our letters will be read and censored,” Kim Aris told CNA on Friday (Jan 31), four years after a military coup that plunged the country into chaos.

“But I know that the conditions that she was being held in, she was feeling the cold and feeling the heat, and she was having ongoing health concerns.”

Since then, Aris, who lives in London, has made numerous attempts to reestablish contact with the long-time democracy icon and Nobel laureate.

“I've sent letters and care packages. I've asked to be allowed to see her in person, as is her human rights. And after all of these attempts, I haven't received any response,” he added.

“I haven't been led to believe that I will receive any more correspondence from her. I haven't had any response from the military to any of my requests.”

BLOODY CIVIL WAR

On Feb 1, 2021, the military seized control and ousted a democratically elected government. Aung San Suu Kyi and other senior figures have been in detention since the coup.

The country soon descended into a bitter civil war that has killed at least 6,000 civilians. More than 3.5 million people have been displaced, and many others have been driven across the borders.

“People in Burma are going through so much worse than what I'm going through,” said Aris, referring to the country's former name which was changed by the military junta in 1989.

“I can only imagine that my mother's going through much worse than I'm going through. And yet she's managing to stay strong.”

Last November, Aung San Suu Kyi's 33-year prison sentence was reduced by six years in a partial pardon.

Aris noted that nobody outside the prison has been able to see her for the past four years, and news about her comes through unverified prison or military sources.

“As far as I'm aware, she's definitely in prison rather than house arrest. Many people think she's still under house arrest or that she was moved to house arrest, but that isn't the case as far as I know,” he said.

“She's been held apart from the other prisoners. So essentially, she's in solitary confinement.”

Aris urged the junta to free his mother and other political prisoners, and return the country to its democratically elected government.

“My mother's going to be 80 this year, and I want to continue to draw more attention to what her plight is and what the plight of the people of Burma is,” he added.

MYANMAR’S STRUGGLING MILITARY

On Friday, Myanmar’s military regime extended a state of emergency for another six months.

However, it is struggling to retain its grip on power, said observers.

The junta has lost huge swathes of territory, including control of two regional military commands, and faces further losses as it continues to battle armed opposition groups for control.

“The Myanmar military is on a clear losing trajectory at this point,” said Jason Tower, country director for the Burma programme at the United States Institute of Peace (USIP), an independent institution established by the US Congress to promote conflict resolution worldwide.

It continues to conduct air strikes, “and that seems to be the main modality that it's using to try to hang on to positions and to deny resistance forces the ability to control territories”, he told CNA’s Asia First.

Military rulers have said they are committed to holding elections this year but opposition groups have derided that as a sham, condemning it as the junta’s strategy to gain legitimacy.

Kyaw Moe Tun, Myanmar’s Ambassador to the United Nations, urged the international community to reject the election, saying it will not be free and fair.

“We need the UN and ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) to play a helpful role to find a sustainable solution to the crisis in Myanmar, in line with the will and interest of the people of Myanmar,” he added.

Moe Thuzar, senior fellow and coordinator of the Myanmar studies programme at the ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute, believes recent developments, including the military losing ground in its war, have made the holding of elections implausible.

ASEAN’S MASSIVE TASK

“It's important that members of the international community, including Myanmar’s neighbours, send a consistent message of concern related to the safety of the people and the will of the people in Myanmar, in relation to any projected elections organised by a military regime that has experienced pushback against it since the coup in 2021,” she told CNA’s Asia Now.

The reality is that Myanmar's junta forces now control less than half the country, added USIP’s Tower.

“That's really why I think one of the reasons why you've seen a lot of the resistance actors condemn them. They don't want the Myanmar military coming into their areas,” he said.

Meanwhile, ASEAN has asked Myanmar's rulers to prioritise peace over elections.

Moe said Malaysia, as the bloc chair this year, should tackle the Myanmar crisis “not as something that can be addressed or solved within the space of one chairmanship year, but look at it in terms of a medium- to longer-term approach where helping the people of Myanmar will go beyond just stopping the violence and the madness and the killings”.

This involves “finding sustainable solutions for helping the people of Myanmar heal and recover from all the violence and atrocities that they have been subjected to these past years,” she said.

ASEAN has been criticised for its approach to the Myanmar crisis, given its internal divisions.

The key challenge is a lack of consensus within ASEAN as to what should be done, said Tower.

“Those divisions make it difficult for ASEAN to act,” he added. “A number of countries are increasingly worried about the situation and want to take more steps to do something about it.”