IN FOCUS: Burn or bury? Malaysia eyes new incinerators to tackle mounting waste woes but faces residents’ ire

While environmental groups and residents have expressed concerns over the risks of the waste-to-energy incinerators, some experts say they are necessary to manage Malaysia’s escalating waste problem.

The waste-to-energy plant that is being built in Jeram, Selangor. (Photo: CNA/Fadza Ishak)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

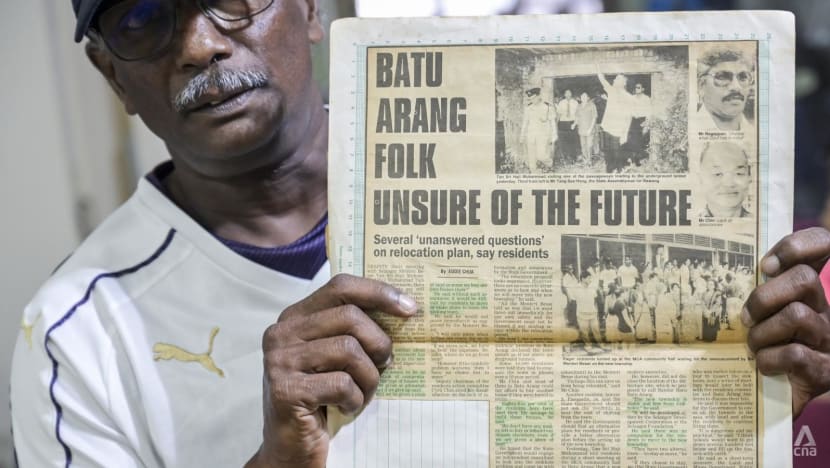

KUALA LUMPUR: In his hometown of Batu Arang in Selangor, 65-year-old Ravi Shankar is rallying against the authorities.

Ravi and fellow residents are fighting the proposed construction of an incinerator, or the Sultan Idris Shah waste-to-energy plant (WTE) - named after the Selangor ruler - in their backyard.

Residents from the nearby areas of Tasik Puteri, Kota Puteri, and Rawang are also mobilising against the authorities, their shared concern stemming from the planned facility's location.

The proposed plant is located next to a former mining pool that has now been sealed off to the public.

“There are still underground tunnels here and we are afraid that if water is needed to cool the incinerator, it might be pumped out again and cause ground instabilities,” said Ravi.

“Our main concern is the location. It is very close to residential areas,” he added.

The protracted dispute in Batu Arang serves as a stark illustration of Malaysia's broader crisis in handling its increasing volumes of solid waste.

This issue is becoming increasingly urgent as the nation's landfills - what the country currently relies on to manage the issue - are expected to be filled to capacity by 2050.

While experts say the WTE incinerators are a necessity to manage the country’s waste management woes, environmentalists and non-governmental groups are expressing concerns over potential health issues and some WTEs’ proximity to residential areas.

For Ravi, his actions are fuelled, not just by concern for the future, but also memories of the past.

Over three decades ago, the town of Batu Arang in Selangor was plagued by land subsidence and sinkholes. Back then, Ravi was among those who protested against a cement company they alleged was the cause of those incidents.

The cement company Associated Pan Malaysia Company had been pumping water from former mining pools for its operations and this was the supposed cause of the collapse of the tunnels located under the town.

The then-Selangor government even told residents that it was unsafe and that they might have to move out.

A series of protests caused the company to stop the pumping of water, and since then, there have been no reported incidents of subsidence in Batu Arang, which was declared a heritage town by the Selangor State Government in 2011 and recognised as part of the Gombak-Hulu Langat Geopark.

“What’s happening today brings back memories of the past,” Ravi, a former supervisor at an ammunition manufacturer, told CNA recently, while holding a scrapbook of old newspaper clippings about the incidents that made headlines in 1991.

He and fellow residents are concerned that the RM4.5 billion (US$1 billion) joint venture between YTL Power and waste management company KDEB could lead to a repeat of past issues.

Driven by evolving consumption patterns, population growth, rapid urbanisation, improved economic standing, and changing consumer habits, Malaysia faces an escalating burden of increasing waste output.

According to Housing and Local Government Minister Nga Kor Ming, last year's waste generation reached an estimated 15.2 million tonnes, a 20 per cent increase from 12.63 million tonnes in 2012.

Projecting a continued annual increase of 0.9 per cent to 1.2 per cent, Nga said in a parliamentary reply last December that Malaysia could see over 17 million tonnes of waste generated annually by 2035.

While environmentalists and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have spoken about their concerns on incinerators, waste management experts have said that WTE facilities are not merely optional but essential for the long term.

“The question is not whether we need it. The question is where do we locate it?” Agamuthu Pariatamby, a waste management expert at the Jeffrey Sachs Center on Sustainable Development in Malaysia, told CNA.

The proposed WTE plant in Batu Arang will be responsible for waste from six municipalities in Selangor, namely Petaling Jaya, Subang Jaya, Shah Alam, Ampang Jaya, Hulu Selangor and Selayang.

In 2022, KDEB reported collecting an average of 6,012 tonnes of waste per day from the whole state of Selangor, with these six municipalities contributing 3,526 tonnes or almost 60 per cent of that total amount.

The plant is said to be capable of processing 2,400 tonnes of waste per day while generating 58 MW of electricity, equivalent to the electricity consumption of 50,000 households, according to an environmental impact assessment by the Department of Energy.

WHAT’S WRONG WITH LANDFILLS?

Currently, Malaysia primarily relies heavily on landfills - both sanitary and unsanitary - for waste disposal.

According to Agamuthu, there are 142 landfills in Malaysia, of which only 21 are sanitary while five are inert sites for construction and demolition debris.

A sanitary landfill is an engineered waste disposal site that isolates waste from the environment using liners, covers, and leachate collection systems, among other things, to minimise pollution and health risks but these measures cost more than unsanitary landfills.

The Bukit Tagar sanitary landfill is an often-cited example of a progressive approach to waste management in Malaysia, as it captures the methane gas produced by decomposing waste and converts it into electricity for the national grid.

Koh Chee Yong, the managing director of Berjaya Enviroparks Sdn BHd, which operates the facility, told CNA that the landfill receives about 2,721 tonnes of waste per day from Kuala Lumpur, as well as the districts of Selayang and Hulu Selangor in Selangor.

Agamuthu is, however, more concerned with the remaining non-sanitary 116 landfills that are active and the other illegal dumpsites around the country. These sites lack adequate environmental safeguards, he said.

He highlighted leachate, the contaminated liquid generated by water filtering through landfill waste, as one of the primary challenges of continuing to dump waste in unsanitary landfills.

He said that uncontained leachate from landfills contaminates groundwater, surface water - harming aquatic life and ecosystems - as well as soil, affecting plant growth.

“The landfills are doing damage, it’s just that people don't see it. Landfills are away from the city … You don't see the leachate. It is flowing underneath,” he said.

“And you can't see the biogas, because it's colourless. But that doesn't mean there's no damage.”

The Department of National Solid Waste Management did not respond to CNA’s enquiries on the subject.

INCINERATING THE RUBBISH

Agamuthu also pointed out that landfills generally take up space and because of land costs, they are mostly located away from urban areas.

“Where is the waste being generated? It’s mainly in the big cities. And big cities have no land.

“That's why they had to find a place about 40km or 45km away to throw the waste in the landfill there,” he said.

“So this becomes an issue. The cost of land is very high within the city. And … the moment you put the landfill far away, the transport cost goes up.”

Nga - the minister - had told Malaysia’s parliament in July of last year that the ministry planned to modernise the country’s solid waste management by setting up 18 WTE plants by 2040. He did not give a projected cost.

The sites are:

- Kedah: Jabi and Padang Cina

- Johor: Bukit Payung, Seelong, and Sedili

- Pahang: Jabor-Jerangau and Belenggu

- Melaka: Sungai Udang

- Selangor: Batu Arang, Jeram, Tanjung Dua Belas and Rawang Dua

- Penang: Pulau Burung

- Perak: Lahat, Taiping, and Manjung

- Terengganu: Tertak Batu

- Kelantan: Jedok

Malaysia currently has five small-scale incinerators that are located in Pulau Langkawi, Pulau Tioman, Cameron Highlands, Pulau Labuan and Pulau Pangkor but these are not WTE plants.

The biggest of these, which is located in Pulau Langkawi, has been plagued with issues over the years and is currently not in operation.

WTEs generate energy from non-recyclable waste by using a controlled incineration method. A crane blends the waste and transfers it to the combustion chamber.

The waste is burned at a high temperature - between 850°C and 1,450°C - and the resulting heat converts water into steam.

In the past, Malaysia has had to shelve proposed plans to build WTE plants in the town of Broga in Selangor in 2007 and in the locality of Jinjang in Kuala Lumpur in 2021 following protests by local residents.

Critics of WTE plants, such as environmental group Greenpeace, have claimed that living near an incinerator poses numerous health hazards, and even the most high-tech WTE incinerators release dioxins and other pollutants into the air.

However, Agamuthu said that the incineration systems have evolved and that the gas cleaning system, or the flue gas cleaning system, is much more advanced compared to 10 years ago.

“So we have systematically removed everything from the flue gas such as the solid particles, biogas, dioxin and fuel. So the gas that's eventually coming out is much cleaner than I would say, the air in Kuala Lumpur,” he said.

“We have been saying no to WTE plants for too long,” he added.

Waste management expert Theng Lee Chong echoed these views and said that there was no running away from WTE plants, saying that in countries such as Japan, incinerators are located within communities.

He has seen how the facilities are located next to a kindergarten and a senior residents’ home, even generating heat for the seniors’ bath.

According to Japan’s Ministry of Environment, there were 1,004 incinerators in the country as of March 2024, with 411 of them able to generate power.

Theng said that while a landfill buries waste, it doesn't eliminate problems entirely.

“It’s underneath and you don’t see it but it will remain there for thousands of years. With an incinerator, there will be ash as a by-product but the volume is reduced by 90 per cent, depending on the technology,” he said, pointing to the likes of Singapore which has four WTE plants, the first of which began operating back in 1979.

Singapore's plants are all in industrial areas, with three located in Tuas and one in Senoko.

The ash and non-incinerable waste like sludge are then placed in the Semakau landfill, which is located about 8km south of Singapore and expected to reach capacity by 2035.

The Singapore government has said that there are ongoing efforts to extend the lifespan of the landfill beyond 2035, as well as research and development into repurposing waste residues such as incineration ash.

For instance, it is studying whether landfilled incineration ash and non-incinerable waste from Semakau landfill can be used as reclamation in the Tuas port project.

Meanwhile, the country has started to repurpose some incinerated ash into NewSand for the construction of non-structural concrete applications such as footpaths and benches.

WTE plants are gaining more traction in the region, with Indonesia announcing in March that it is set to develop 30 WTE plants in major cities across the country by 2029.

Thailand is also planning on adding more WTE plants in the country, with at least 25 operating in the country as of 2022.

There have been protests against the plants in these countries in the past, but the governments have had to push ahead with their WTE plans given that they face similar challenges on mounting waste as Malaysia.

According to Theng, if Malaysia’s landfills were reclaimed for future development, remediation costs would be necessary.

Remediating a former landfill involves restoring the site to a usable condition after it has been filled with waste and closed.

“You don’t factor in the opportunity costs that you cannot use or develop the land for, say for 100 years,” he said, referring to the lost potential and value of that land being unavailable for other development for a very long duration.

He also pointed out the significant suffering of communities near landfills, who often endure foul odours, increased vermin and pest populations, decreased property values, and the general degradation of their living environment.

Just weeks ago, it was reported that residents of Kampung Desa Makmur in Kota Tinggi, Johor, have been protesting the Batu Empat landfill, which they say has been causing severe odour pollution for almost 20 years.

In response, Johor’s Housing and Local Government Committee Mohd Jafni Md Shukor was reported to have urged the federal government to expedite the construction of a WTE plant at the Bukit Payong Sanitary Solid Waste Landfill near Batu Pahat.

Theng said that there was no single formula for waste management and one technology cannot apply to the whole country and that in order to operate a WTE sustainably, it must receive at least 500 tonnes of waste daily.

However, he hoped the government would explain the long-term financing model for the WTE plants, specifically whether it would involve a public-private partnership, especially as there were substantial costs in building them.

“How will the government close the financial gap? Will the consumers have to pay more for the waste management? This part has yet to be explained,” he said.

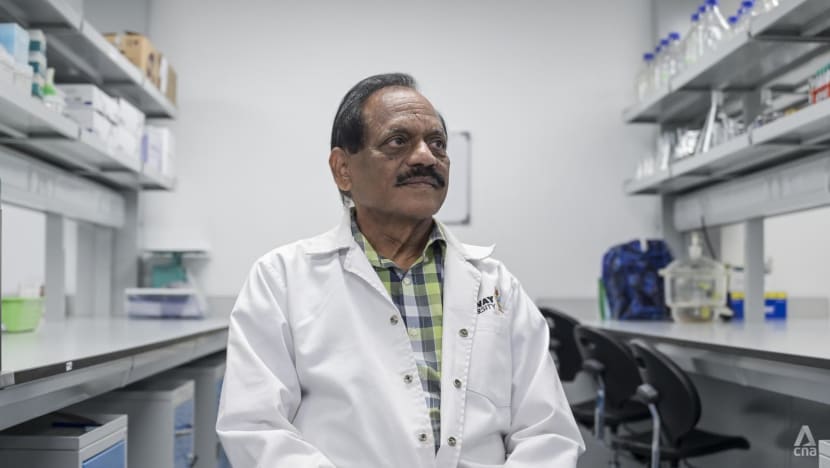

Seeram Ramakrishna, a professor at the National University of Singapore’s Department of Mechanical Engineering, told CNA that WTE plants are a “stepping stone” to deal with the whole issue of waste.

He said that compared to conventional landfills, WTE plants create value from waste by generating energy and that Singapore's well-developed WTE infrastructure was initially a necessity due to its limited land availability.

He added that while WTEs offer a degree of progress through energy generation, it is crucial to ensure stringent emission controls.

“WTE facilities must guarantee that their emissions pose no threat to human health and that the released air is of high quality – this is a fundamental expectation,” he said.

WHERE DO YOU LOCATE IT?

The central question, Agamuthu posed, was the crucial issue of WTE plant location, given the common "not in my backyard" sentiment among residents anywhere in the world.

Jaringan Rawang Tolak Insinerator is an NGO that has been actively protesting and voicing its concerns against the planned incinerator in Batu Arang, submitting objections to local authorities.

Its spokesperson Abdul Hanan Abd Mokti told CNA that the proposed incinerator site is very close to vulnerable communities.

“The selection of Batu Arang continues the worldwide trend of locating incinerators in marginalised and less-affluent communities,” he said, adding that an estimated 100,000 residents reside within a 5km radius of the proposed site's centre.

He also asked the basis of selecting Batu Arang and Rawang - located about 17km apart - for the sites of two proposed WTE incinerators, fearing that the area will be overwhelmed by garbage trucks travelling to the incinerator via local roads.

“Why are so many of these high-risk, highly toxic projects being concentrated in the same district?,” he said, adding that there are worries that property values in the area may plummet because of the projects.

According to the Department of Energy environmental impact assessment report which was released on May 7, 91.3 per cent of respondents surveyed in 2025 either opposed or strongly opposed the Sultan Idris Shah project, compared to just 18.8 per cent of respondents in a 2023 survey.

The report attributed the significant decline in support for the project to the increased public awareness of it.

A WTE plant is already being built at the Jeram sanitary landfill in Kuala Selangor. However, unlike other WTEs, not much opposition has been registered towards it.

It is located about 5km away from the nearest residential areas and is surrounded by palm oil plantations. It is expected to start operating next year, according to media reports.

The project is a joint venture between Worldwide Holdings Berhad, a Selangor state-owned company and Shanghai Electric Power Generation (M) Sdn Bhd (Shanghai Electric). The plant is designed to process up to 3,000 tonnes of solid waste daily.

Aziah Parini, a resident of Kampung Bukit Kerayong 1 - located about 5km away from the plant - told CNA that several NGOs had come to the village to speak about the dangers of the incinerator.

However, the 49-year-old, who operates a food stall, said that they were not worried about the plant.

“We can only hope for the best and that it will not affect the people around here,” said the grandmother of one.

IMPROVE THE RECYCLING RATE

Despite differing opinions on specific waste management solutions, there is a fundamental agreement among all waste management experts and NGOs: The sheer volume of waste Malaysians generate must be significantly reduced at its source.

According to deputy housing and local minister Aiman Athirah Sabu, the national recycling rate increased to 37.9 per cent in 2024 from 35.4 per cent in 2023, but still hasn't reached the 40 per cent target for 2025.

The average waste generation per capita in 2022 was estimated at about 1.05kg per day, significantly higher than that of other Asian countries which range from 0.4 to 0.7 kg per day, said Agamuthu.

Agamuthu believes that the amount of waste is increasing because of the sophistication of people’s standard of living.

“The more affluent we are, the more waste is generated,” he said.

He added that while the rising standard of living generally meant more waste, the amount per capita in Japan has reduced over the years because of focused policies and public awareness.

“They are already educated enough to reduce the waste themselves,” he said, adding that the layperson should be educated on their responsibility of waste separation at source.

Seeram said that effective waste management necessitates a primary focus on source segregation, as this practice unlocks the potential for “waste mining” and the creation of valuable resources.

"Ideally, WTE initiatives, while a treatment method, should align with the principles of a circular economy, viewing waste as a resource.

"This requires the development and implementation of robust processes for waste segregation and cleaning to facilitate resource recovery, which represents the most desirable long-term scenario," he said.

He added that WTE should not be perceived merely as a temporary step towards better waste management and that instead, the fundamental focus must remain on controlling and reducing waste at its source.

"Japan for example excels in waste management compared to many other nations, largely due to its ingrained cultural values," he said.

Tasha Sabapathy, a senior programme and communications officer of Zero Waste Malaysia - an NGO that promotes a zero waste lifestyle - told CNA that the government should prioritise solutions based on the context that food waste is the majority of waste.

The composition of household waste in Malaysia in 2022 was dominated by food waste (30.6 per cent), with plastic (21.9 per cent) and paper (15.3 per cent) making up the next largest segments.

Sabapathy said she wants to see an increase in composting facilities as well as community composting initiatives. She also advocates the banning of single-use plastics, noting how some restaurants these days even use plastic packets instead of cups to serve drinks.

She said that the public should ultimately understand what happened to their waste.

“What happens after we drink a coffee (purchased) from a store. Where does the cup go? If it gets recycled, they won’t care. But the truth is it cannot be recycled because of the way it is made. It is the same for any kind of waste.

“We need to know what happens to it and who are the communities affected and bring that education to everyday people. Then we will understand why we need to be responsible for it,” she said, adding that incineration discourages recycling.

One of Bukit Arang’s resident Yap Wan Ken, 53, acknowledges that while people could register their protest against the incinerator, everyone has a role to also reduce their own waste.

She recycles as much as possible and composts her wet household waste. She has used the compost to grow her own flowers, vegetables, and fruit, such as pineapples.

Yap, who works in finance, said that global warming is not a joke and hopes that what she does contributes to the betterment of the environment.

“We are the ones who also contribute to the waste, it doesn’t generate on its own. I always believe solutions to an issue are always at the source, not at the end, in order for long-term success.

“I hope our government and fellow Malaysians can work together to reduce waste at the source for the sake of the environment and minimise the need for incinerators,” she said.