IN FOCUS: As Malaysia corruption dragnet widens, PM Anwar's 'political payback' threatens to hurt business sentiment

Malaysia’s anti-corruption crackdown is turning into a high-wire political act for Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim, amid mounting criticism that the campaign smacks more of a witch hunt of former and current political foes.

A woman walks by the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC) in Putrajaya on Jan 3, 2024. (Photo: CNA/Fadza Ishak)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

KUALA LUMPUR: Amid Malaysia’s high-profile raids in recent months by its anti-graft busters as part of the country’s most extensive crackdown on corporate corruption, one has flown under the radar but stirred disquiet within the country’s clubby corporate and banking circles.

In late March, Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC) investigators made surprising simultaneous swoops on the offices of former finance minister Daim Zainuddin at the prestigious 60-storey Menara Ilham and the publicly listed Protasco Bhd, an investment holding company with extensive interests in road maintenance operations throughout the country.

News of the raid on Protasco, which has not surfaced in public until now, quietly spread like wildfire in the corporate and banking sector as it marked the first time a listed entity had been caught in the crosshairs of the probe against Daim and his previous political boss, former premier Dr Mahathir Mohamad.

In a country where business and politics have long been intertwined and where many tycoons from companies listed on the Malaysian stock exchange have relied on the ruling elite for public projects and other government largesse, the widening crackdown is stirring unease because of potential pitfalls facing businesses stuck on the wrong side of the political divide.

“People are using the word ‘vendetta’ and the pattern emerging is that those close to former senior politicians are becoming targeted by the new government, and it does not matter how far it goes back,” said a chief executive of a state-controlled local commercial bank, who declined to be named. He noted palpable nervousness among many of his corporate clients over the ongoing crackdown.

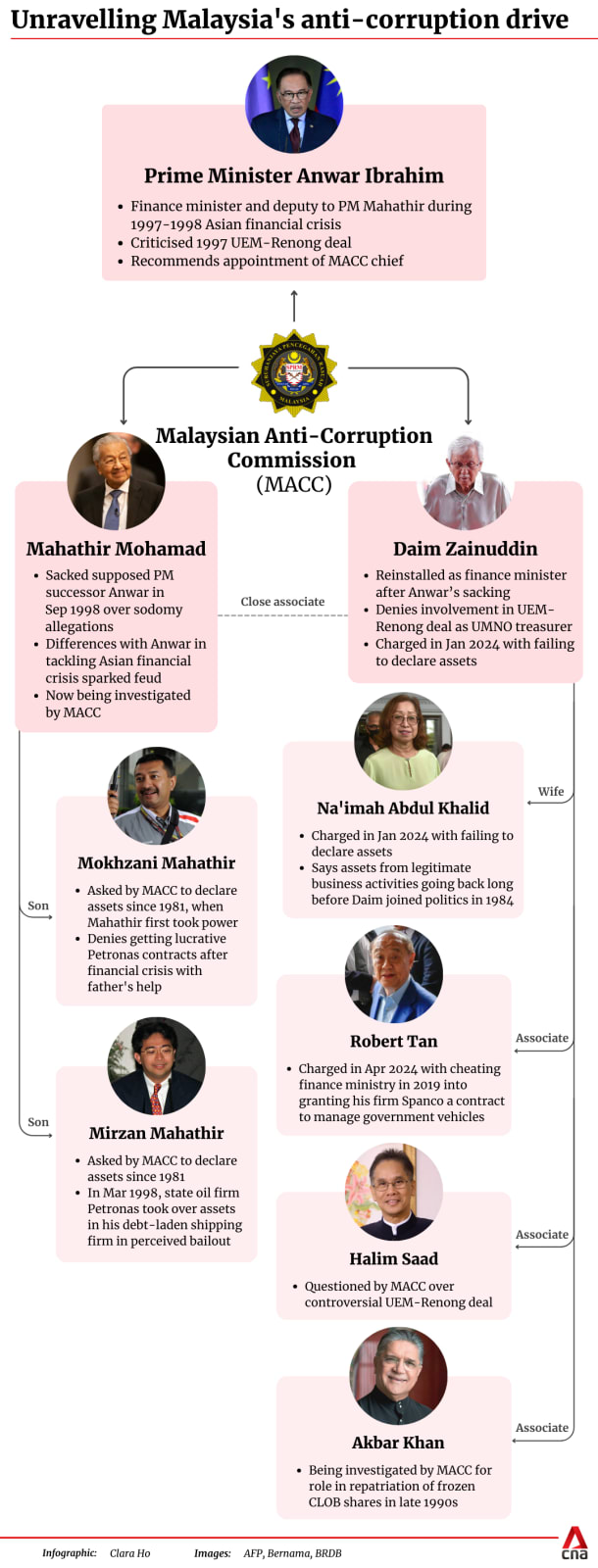

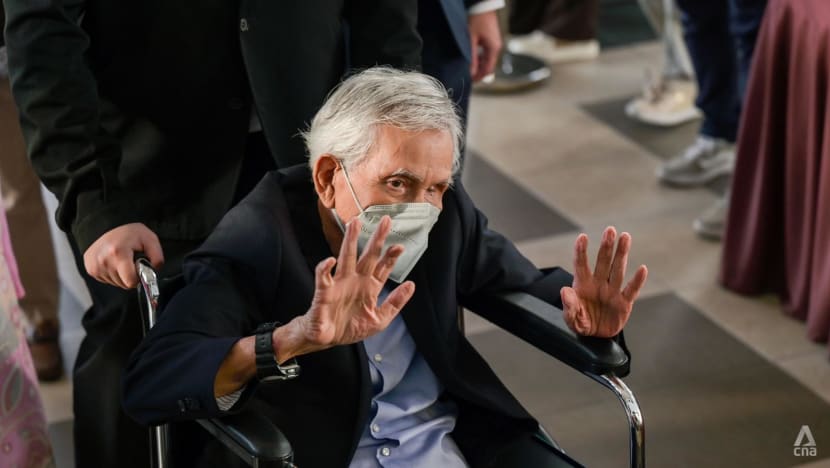

Dr Mahathir – the 98-year-old two-time former premier who was confirmed last month by the MACC to be under investigation – and Daim were the chief architects of Malaysia’s controversial political economic model that nurtured many of the corporate entities since the mid-1980s that today dominate the national economy.

Now that the once-powerful figures are under the pincers of the authorities, corporate chiefs who benefited are beginning to feel the heat. These include one-time corporate heavyweights such as Halim Saad, who previously controlled a clutch of public-listed entities, property developer Akbar Khan and “Casio king” Robert Tan Hua Choon.

The Protasco visit was part of a widening probe into the business affairs of Daim and his family, sources say.

According to the MACC sources, Protasco was a huge beneficiary of road maintenance contracts from the government, and is tied to the agency's December seizure of Menara Ilham, a high-end office and residential building in the heart of Kuala Lumpur’s financial district belonging to Daim’s family. The MACC sources declined to elaborate. Protasco did not respond to a request for comment.

The anti-graft campaign is also taking a political slant.

Public cynicism is running high over the Anwar administration’s ongoing crackdown, with some questioning if it is less about reforms than another episode of “political payback” against old foes and those who are trying to topple his government.

On May 7, at an event to launch Malaysia’s new national anti-corruption strategy, Mr Anwar defended the probes, saying that the country needed to be saved from “greedy” people after the country lost RM277 billion (US$58.4 billion) to corruption from 2018 to 2023.

“Every time action is taken (against high-profile individuals), many complain and sigh. Some even defend them and give excuses: ‘Enough already. Don’t take revenge, they are already old,’” he said.

“I congratulate and salute those who take action against them.”

Analysts say Mr Anwar should do more to stave off allegations of political payback by introducing institutional reforms that improve governance.

Dr Ong Kian Ming, a former international trade and industry deputy minister, told CNA that this should include making the MACC more independent, by ensuring the appointment of its chief is done at the recommendation of parliament or a commission of well-respected figures.

Currently, the MACC is under the Prime Minister’s Office, with the prime minister recommending the appointment of MACC's chief commissioner.

“The key point here is to ensure that MACC investigations are not only seen as independent but also are independent,” said Dr Ong, who is also a senior representative of the Democratic Action Party (DAP), a main component of Mr Anwar’s ruling coalition.

“People would be more convinced that these anti-corruption efforts are genuine if they were accompanied by institutional reforms.”

BACK TO THE FUTURE

Malaysia’s political and economic infrastructure has long been shaped by the close intermingling of politics that has bred a class of hugely wealthy capitalists with links to those in power, who were showered with economic opportunities like licences and lucrative government contracts.

But this controversial model is often tested during times of political crisis when observers note that those in power have been perceived to “weaponise” agencies such as the MACC, police and the stock market watchdog Securities Commission, to crack down on political and business opponents.

This became more apparent during Malaysia’s political upheaval following the May 2018 general election, which saw the ruling Barisan Nasional toppled from its 60-year reign and, subsequently, power changing hands three times.

Dr Mahathir, who led the opposition campaign in the May 2018 general election and became premier for a second time, quickly moved against his political opponents in the once-dominant United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), including Najib Razak and his deputy Mr Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, with corruption investigations by the MACC.

Dr Mahathir’s government also dropped corruption charges against then-DAP chief Lim Guan Eng, who was later appointed finance minister in an administration that lasted 22 months. Lim was subsequently handed fresh corruption charges when the Mahathir administration fell. The trial is ongoing.

The anti-corruption drive took a back seat under the brief premierships of Muhyiddin Yassin and Mr Ismail Sabri Yaakob. It quickly resumed after Mr Anwar was elected prime minister following the inconclusive November 2022 general election.

The new Anwar government first trained its guns on Muhyiddin and his Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia (Bersatu) with charges of power abuse, money laundering and corruption in his previous administration’s multi-billion-dollar COVID-19 stimulus programme.

The government also froze over RM300 million in Bersatu’s bank accounts in several financial institutions that were amassed during the party’s leadership of government for 17 months.

The Anwar government’s anti-graft purge began to be viewed through a political prism sometime in April 2023, when the MACC began dialling back to controversial corporate transactions that were considered hot-button issues in the political confrontation between Dr Mahathir and Mr Anwar that began in late 1997.

FROM ALLIES TO FOES

November 1997 – With foreign and domestic investors already skittish amid the Asian financial crisis, United Engineer Malaysia (UEM) buys a 33 per cent stake in its debt-laden parent Renong for RM2.3 billion, sparking a bloodbath in local financial markets as UEM investors dumped their shares and halved Renong’s value.

The controversial deal, perceived as an effort to save Renong, a cornerstone of the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) business empire, sowed the seeds of political tension between Finance Minister and Deputy Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim, and Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad as well as UMNO treasurer Daim Zainuddin.

March 1998 – A controversial plan by Petronas to take over the shipping assets belonging to Dr Mahathir’s eldest son, Mr Mirzan Mahathir, sows further political discord between Mr Anwar and his boss over the use of public funds to rescue politically-connected groups.

May 1998 – The political and economic turmoil in Indonesia that led to the fall of former strongman Suharto raises speculation of a possible regime change in Malaysia and further strains ties between the factions in the ruling elite led by Dr Mahathir and Mr Anwar.

June 1998 – UMNO youth chief Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, a close associate of Mr Anwar, speaks at the party’s general assembly about corruption, collusion and nepotism, a popular tagline in the anti-Suharto campaign and an apparent jibe at the Mahathir administration.

In response, Dr Mahathir distributes a list showing people who benefited from privatisations, featuring his son Mr Mirzan and the deal involving Petronas. But in the list are also Mr Ahmad Zahid himself and relations of Mr Anwar. He chides Mr Ahmad Zahid for not using proper party channels to voice complaints, and defends his pro-Bumiputera policy as a basis for the privatisations.

September 1998 – After a series of political skirmishes, Dr Mahathir moves to sack Mr Anwar from government, leading to the latter’s subsequent trials and long jail sentences for sexual misconduct and corruption, developments that pushed Malaysia into a period of prolonged political uncertainty. Daim is subsequently reinstalled as finance minister.

May 2018 to November 2022 – At the May 2018 general election, Dr Mahathir and Mr Anwar join hands to defeat the long-established Barisan Nasional coalition plagued by the 1Malaysia Development Berhad scandal. Daim is appointed chief of an advisory council to the new premier Dr Mahathir.

But in less than two years, Malaysia’s political and economic uncertainties deepen with the collapse of the Mahathir administration. Political power changes hands thrice before a unity government led by Mr Anwar takes control following the inconclusive November 2022 general election, which sees Dr Mahathir lose his seat in a shock defeat.

April 2023 – The Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC) begins its investigations into Daim and dials back to review transactions that were sources of tension between the Mahathir-Daim combo and Mr Anwar in the late 1990s.

A number of people are hauled up for questioning, including businessman Halim Saad, who was the chief corporate nominee for UMNO, which was headed by Dr Mahathir, while Daim served as its treasurer.

December 2023 – MACC moves in on Daim, slapping him and his wife, Na’imah Abdul Khalid, with asset declaration orders and sequestering the family’s flagship corporate headquarters, Menara Ilham, in the capital Kuala Lumpur.

January 2024 – MACC anti-graft probes into Daim expand to the defunct Singapore trading platform known as CLOB and to his close business friend, Akbar Khan.

February 2024 – High-profile corporate bailouts of the Mahathir era come into focus in the ongoing MACC investigation, including the controversial bailout by national oil corporation Petronas of the shipping assets owned by the former premier’s eldest son, Mirzan Mahathir.

Mr Mirzan and his brother Mokhzani are also slapped with asset declaration orders by the MACC.

April 2024 – A long-time Daim business acolyte, Robert Tan Hua Choon, whose Spanco Sdn Bhd operates the government vehicle fleet management concession, is charged with cheating the government into giving his company a contract.

MACC chief Azam Baki also reveals that Dr Mahathir is being investigated in a probe linked to his sons’ asset declaration orders. Mr Azam did not elaborate on the nature of the investigation.

Political tensions at the time were first triggered by a controversial RM2.3 billion transaction that took place in November 1997 involving public-listed entities Renong Bhd and United Engineer Malaysia Bhd (UEM), which together stood at the heart of the business empire of the then-ruling UMNO party.

The deal, which involved cash-rich UEM taking over a controlling equity interest in debt-laden Renong, caused a meltdown in the Malaysian stock market as UEM investors dumped their shares, complaining that the company’s health was sacrificed to shore up Renong.

The controversial deal soured relations between Mr Anwar, who was finance minister at the time, and his predecessor Daim, who controlled UMNO’s business interests as the party’s treasurer through his business nominees.

Daim now maintains that the UEM-Renong deal was purely a corporate transaction between companies that were governed by their respective managements, board of directors and shareholders, said financial executives close to the former politician.

Those tensions soon morphed into a bloody political battle between Mr Anwar in one corner, and the Mahathir-Daim combo in the other.

While Dr Mahathir was bent on using state funds to protect troubled businessmen that his government had entrusted to take on quasi-official projects under the country’s privatisation programme, Mr Anwar favoured a more free-market approach to deal with the country’s economic woes and advocated a policy of high interest rates to attract foreign funds to prop up the ringgit that had fallen sharply in value.

But the strategy of high interest rates choked economic activity and, more importantly, became a direct threat to Dr Mahathir's economic model because it made it difficult for the well-connected political business groups to service their debts and finance big-ticket infrastructure projects.

The bailout by state oil corporate Petronas of Mr Mirzan’s Konsortium Perkapalan was the first among a series of controversial corporate deals that sowed the seeds for the Mahathir-Anwar policy face-off that later morphed into a full-blown political battle that lingers to this day.

MACC officials, who spoke to CNA on condition of anonymity, said that apart from the order for Dr Mahathir’s two sons to declare their financial holdings, the agency is also probing the former premier’s alleged involvement in directing Petronas to initiate the takeover of Konsortium Perkapalan.

Daim was charged in January together with his wife Na’imah Abdul Khalid for failing to declare their assets involving 38 companies, 25 properties and several luxury vehicles. Both pleaded not guilty.

Daim and his family have also failed in multiple bids to start judicial review proceedings over MACC's probe into their financial affairs, Free Malaysia Today reported. On May 9, the Court of Appeal dismissed their appeal against the High Court’s rejection of their application.

The High Court had ruled that Daim and his family failed to establish that MACC investigating officers conducted the probe in bad faith.

In May last year, local media reported that MACC was investigating a former senior minister and a businessman holding the title of “Tan Sri” over alleged embezzlement of state funds.

Various outlets said this was understood to be a reference to Daim and businessman Halim Saad, and their alleged roles in the UEM-Renong deal. Mr Halim was reported to then be holding shares in both UEM and Renong as UMNO’s proxy.

Daim is also being investigated over his involvement in separate corporate exercises involving the now-defunct Singapore-based trading platform called the Central Limit Order Book (CLOB), and the takeover of a large conglomerate called Multi-Purpose Holdings Bhd in the late 1990s.

These deals were spearheaded by Mr Akbar Khan, who has long been a close business acolyte of Daim. Mr Akbar is under probe by the MACC and has been ordered to declare his financial holdings to the agency. He has not responded to requests for comment.

Another Daim-linked businessman in the MACC dragnet is Robert Tan Hua Choon, who is the controlling shareholder of privately held Spanco that offered vehicle fleet management services to the government from 1993 to 2019.

Tan was in April charged with cheating the finance ministry in 2019 into awarding Spanco a contract to run government vehicles. The businessman, who is also the sole distributor of Casio watches and calculators in Malaysia, pleaded not guilty.

WHY "WITCH HUNT" ACCUSATIONS PERSIST

Despite Mr Anwar’s repeated assertions that his government is determined to stamp out widespread corruption and that the MACC is not being selective in picking its cases, accusations persist that the campaign is very much a witch hunt.

In 1998, just as it seemed Mr Anwar was poised to be the next premier, he was sacked from the Cabinet over allegations of sodomy, which he has always denied.

The next year he was charged with sodomy and corruption, and he was eventually sentenced to six years in jail for corruption, with a nine-year prison term added for the sodomy charge the following year.

He was assaulted in prison and appeared in public with a black eye, inflicted by Malaysia’s then-police chief. Photos of Mr Anwar with a black eye became synonymous with his supporters’ battle cry of “reformasi”, or reforms.

Mr Anwar was released in late 2004 after his convictions were overturned before returning to lead an opposition coalition in the 2013 general election. But he was jailed again in 2015 on new sodomy charges that had been made in 2008.

In 2018, Mr Anwar was granted a royal pardon and he returned to parliament months later in a by-election.

DAP’s Dr Ong believes Mr Anwar is using the current investigations to show he is going after some of the “big fish” and is serious about tackling corruption.

But he said the Malaysian public these days is “much more politically mature” and would have realised a lot of these people could be considered Mr Anwar’s political rivals or their allies.

“It is hard for political observers and even the average person to imagine that this is not political payback especially since the cases involving Mirzan and Mokhzani Mahathir include asking them to declare the source of their assets going back 43 years,” he added.

After being charged, Daim accused the current government of abusing its power and “betraying all the promises of reform". "I am not too bothered about my fate now, let Anwar throw everything at me," he said at a press conference.

Daim’s wife Nai’mah accused Mr Anwar of pursuing political revenge, warning the premier that power is “fleeting”.

Analysts told CNA it is difficult for Mr Anwar to stave off allegations of selective prosecution when those who had faced similar charges of corruption but are now in government with him walk free.

In September 2023, Malaysia’s High Court granted a request from prosecutors to drop 47 corruption charges against Deputy Prime Minister Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, a decision that triggered protests and widespread criticism.

Mr Anwar maintains that he did not interfere in the move, saying it was purely a decision by the attorney-general.

“If you’re investigating Mahathir’s sons and Daim and his family, and asking them to declare their assets, why aren’t you asking the same of Zahid?” asked Dr Edmund Terence Gomez, a political economist who has written extensively about the politico-corporate scene in Malaysia.

Associate Professor Salawati Mat Basir, legal advisor at the National University of Malaysia, asserted that the MACC faces political pressure to put certain people behind bars.

The ground sentiment, she said, is that MACC’s investigations “suddenly” switched gears to focus on people who were Mr Anwar’s rivals or close to them, whereas probes into more recent issues seem to have stalled.

These include the Littoral Combat Ship scandal, where Malaysia was supposed to get six of these warships by 2023 but none have been delivered thus far, despite the government already paying around RM6 billion, or two-thirds of the total cost of the contract.

While a former navy chief was in 2022 charged in connection to the deal, critics have questioned why there now seems to be all-round silence despite the government's assurance of getting to the bottom of the issues previously raised.

These include questions of governance and transparency that remain unanswered, including the rationale for awarding the contract to Boustead Naval Shipyard in 2011 through direct negotiation, and holding those responsible accountable.

A public governance, procurement and finance report revealed that Mr Ahmad Zahid, who was defence minister at the time, was involved in the procurement process.

“It involves Zahid Hamidi, and people are questioning why he always gets that kind of immunity, while (the government) wants to dig into all those old cases and so on,” Assoc Prof Salawati said.

According to a Malay Mail report on Apr 25, MACC chief Azam Baki said the probe into the scandal is ongoing, adding that investigations took a long time because the agency needed to trace the money and apply for Mutual Legal Assistance to get documents and evidence from abroad.

Member of Parliament for Muar Syed Saddiq Syed Abdul Rahman feels the Anwar administration, like the Muhyiddin government, is using the MACC to go after political rivals.

The former youth and sports minister is appealing against a conviction for corruption offences, including abetting a former Bersatu official in misappropriating RM1 million for the party's youth wing.

Syed Saddiq claims he was sacked from Bersatu in 2020 because he did not back the Muhyiddin-led government. He was charged with the offences when Muhyiddin was premier.

“They (the Anwar administration) are going on the offensive by portraying their political opponents as corrupt as well, hoping that the public will then say, ‘There’s corruption on both sides, so let's just move forward,’” he said.

Syed Saddiq stressed that it is crucial for Malaysia - which aspires to be a developed country - to have “strong democratic institutions” that will outlast any government or political personality.

“The problem in Malaysia is that while we are a nascent democracy, our institutions are still not fully independent,” he added.

"JUSTIFIED" MACC CAMPAIGN

Still, Dr Gomez said the MACC campaign was justified as there seems to be more than enough evidence - including from the Pandora Papers - to suggest these individuals should be investigated.

“Prosecutions will happen if the MACC gets enough to go on,” he added.

DAP’s Dr Ong said a perception that these investigations are only for show and will not be prosecuted might “not be necessarily correct” as other high-profile corruption cases, like the one involving Najib, led to a conviction.

“Given the resources available to these individuals, their cases may be tied up in court proceedings for a long period of time,” he said.

“The legal process, including the court declarations about the assets of some of these individuals, will also probably tarnish the public image of some of these individuals.”

The concern, he said, is that such graft investigations with a political tint will lead to “tit-for-tat” actions against those who are currently in power if the opposition wins at the next general election.

“There will be a cycle of political payback whenever there is a change in government and it may distract from the more important agenda of putting in place substantive institutional reforms which are necessary for long-term improvement in governance structures in the country,” he added.

Beyond that, policy and institutional changes can help address accusations of politically motivated probes, observers say.

The government’s new national anti-graft strategy involves financial incentives for whistleblowers and education in schools.

The strategy has five main categories of measures - education, public accountability, the people’s voice, enforcement, and incentives - and covers risk areas like political governance and public procurement.

The political economist Dr Gomez questioned why the government was taking so long to implement other reforms for better governance that activists have long asked for.

These include measures like introducing a political financing law and separating the powers of the Attorney-General and Public Prosecutor, both of which are in the works under the Anwar administration.

Dr Gomez feels the government is dragging its feet because it lacks the political will to push through reforms that would loosen its grip on power.

“A lot of power is already concentrated with the prime minister. Why would he want to take all this power away, especially when he’s dealing with an electorate that voted for a hung parliament?” he said.

“But it’s an urgent task if you want the economy to thrive and investments to come in.”

Dr Ong said the ongoing crackdown could lead to capital flight or a long-term decrease in domestic investments in Malaysia.

“Some Malaysian businessmen would prefer not to deal with the possibility of being involved in political actions and recriminations as a result of political fights,” he said.

“These businessmen would prefer to take their money out of the country and seek investment opportunities abroad, or if they have already substantial assets overseas, they would not want to bring back much of their wealth to invest back in Malaysia.”

Despite criticism of the ongoing corruption crackdown, many analysts see it as necessary in a country that is ranked 57th among 180 nations in Transparency International’s global corruption perception index.

Mr Jais Abdul Karim, president of Malaysia Corruption Watch (MCW), is in full support of Mr Anwar’s anti-graft campaign.

He called it a clear sign that the new government is determined to end the era of impunity among high-profile figures, and demonstrate “equality before the law, regardless of one's status or influence”.

"MCW believes in the relentless crusade against corruption, and with PM Anwar's strong political will, we are confident that Malaysia is moving in the right direction with its anti-corruption policies," he said.

Mr David Gerald, who spearheaded efforts by Singaporean investors to free around S$5 billion worth of frozen CLOB shares, told CNA he will be watching the investigation involving Mr Akbar closely.

“I was, as many CLOB investors, puzzled as to why a private organisation was pulled in to be involved in the settlement,” said Mr Gerald, who is also president of the Securities Investors Association Singapore.

Mr Gerald said he had wanted the issue of settlement to only involve the bourses of Malaysia and Singapore, and that he now hopes the probe will answer why a private organisation led by Mr Akbar was engaged.

“I was truly disappointed that many private individuals or businessmen from Malaysia came to see me with all sorts of settlement proposals largely designed to benefit themselves,” he added.