Child sex crimes and child porn on the rise in Malaysia as police, experts identify challenges and solutions

The Royal Malaysia Police says it could do with more manpower and expertise to better investigate these crimes.

File photo of children playing football in Kampung Baru, Kuala Lumpur. (Photo: CNA/Fadza Ishak)

KUALA LUMPUR: In the depths of the sprawling, bustling Royal Malaysian Police's Bukit Aman headquarters, Assistant Commissioner of Police (ACP) Siti Kamsiah Hassan's firm voice rang out from her cosy office as she recounted a recent child sex crime case.

A seven-year-old girl had just endured the trauma of her parents getting divorced, and her uncle decided to "take advantage" of the circumstances, said ACP Kamsiah, who is principal assistant director at the Sexual, Women and Child Investigations Division (D11).

"He gave an excuse of wanting to heal and console this child, to improve her family situation. So he took her out, and molested and raped her," she said.

The details were harrowing, but ACP Kamsiah spoke in a matter-of-fact tone – a testament to the seven years she has spent in the division.

"The seven-year-old didn't understand this situation. The perpetrator even recorded his acts and uploaded the clips on a file storage site," she added.

What the man did not know was that this cloud platform had active policies against child sexual abuse material, colloquially known as child pornography. It detected this content and reported it to the police.

Officers identified and arrested the man. They also found explicit videos and further evidence of his sex crimes against this child.

The man eventually confessed, ACP Kamsiah said, adding that the incident occurred seven years ago but was only recently reported.

RISE IN CHILD SEX CRIMES AND CHILD PORN

In Malaysia, more children below 18 are being sexually abused.

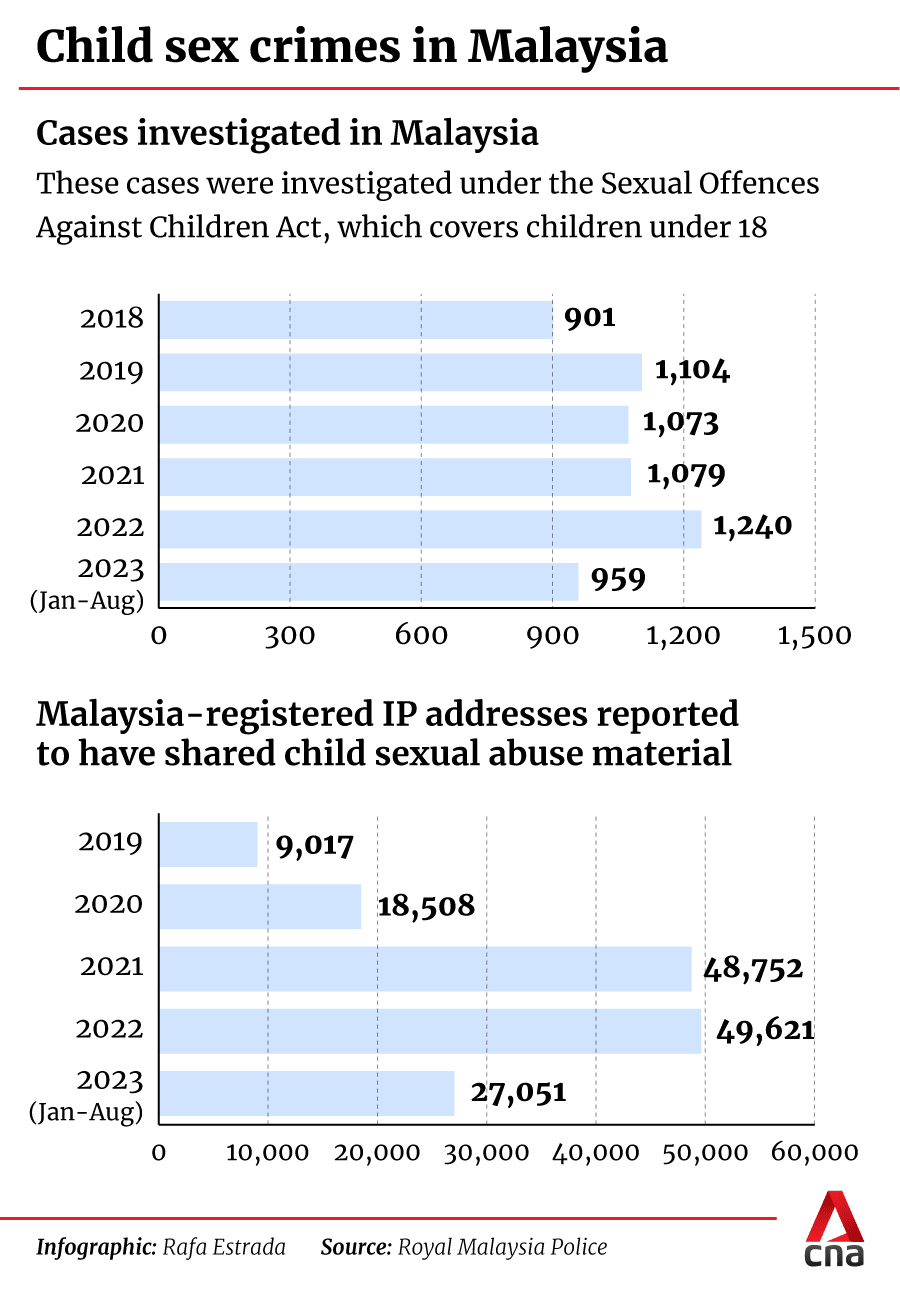

In 2022, police investigated 1,240 cases under the Sexual Offences Against Children Act, up from 901 cases in 2018. Latest statistics provided show that 959 cases were opened from January to August 2023, already a higher monthly average than 2022.

"There has been a slight increase year-on-year, but what is frightening or concerning is the percentage of victims who are children," ACP Kamsiah said.

In previous years, half to 60 per cent of sex crime victims in general were children. This year, it has gone up to 70 per cent, she said.

"(The ratio) shows that for sex crimes, including those involving pornography, the main targets are children," she added.

These offences range from producing and sharing child videos to sexual grooming as well as physical and non-physical sexual assault of children. Non-physical assault involves exposing a child to sexual or indecent situations.

ACP Kamsiah said a majority of cases involve perpetrators who are known to the victims, including family members and friends.

Most victims are aged between 10 to 15 years old, she said, as this is when they start creating social media accounts and using them to communicate.

Beyond that, more people in Malaysia are also accessing and sharing child sexual abuse material.

According to police statistics, 49,621 Malaysia-registered internet protocol (IP) addresses were reported to have shared such material in 2022, a more than five-fold spike from the 9,017 addresses in 2019. The total for January to August 2023 is 27,051 IP addresses.

During his budget speech in February, Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim announced that the police's D11 unit would be "more aggressive" in investigating sexual abuse cases involving women and children.

Divisions under the police's Criminal Investigation Department start with D, with D10 for instance referring to the forensics division.

Mr Anwar also revealed that the police had recently set up a "special team" under the unit to combat child pornography and cooperate with various agencies to arrest the perpetrators involved.

ACP Kamsiah acknowledged that child pornography is a problem in Malaysia as it is a crime that "very easy" to commit in an increasingly digital world, with victims who are easily influenced.

Child experts told CNA that for the situation to improve, both enforcement and care agencies - including privately-run children's shelters - need to better coordinate their efforts and resources. They also stressed the need for better support systems at the community prevention level.

MODUS OPERANDI

Dr James Nayagam, a child development expert who helps place children across a network of five shelters, said he gets about three cases a week involving child sexual abuse.

These reports come from a variety of sources, including the victims' schools, friends and neighbours. Many of them also involve perpetrators who are known to victims, like a brother or uncle.

Dr Nayagam has also been called in to assess children who are having problems in school and are suspected to have experienced sexual abuse. He described some signs he saw that confirmed initial suspicions.

Some younger girls would start playing with dolls inappropriately, while older victims would want to get intimate with boys or even older men, he said.

"Some of them are, say, nine or 10 years old, but they behave like they are 16 years old," he said. "So immediately I say, oops, there's a problem."

Dr Nayagam said a majority of child sex crimes take place in low-cost government housing. These flats, described by one media report as the "slums", are often cramped and unsanitary.

"During COVID, everybody staying there cannot go out. The incidences of abuse go up. Father lost a job, no business, no taxi-driving, so he gets angry," he said. "You see, sexual abuse is a sub-product of a bigger issue."

Many of these cases also go unreported as the crime takes place behind closed doors, and the victims are too young to speak out.

In one case that Dr Nayagam handled, the victim's mother knew what was going on but did not report it as she had grown dependent on the perpetrator - her boyfriend - for food and shelter, he said.

"The man continued raping the eight- and nine-year-old girls every day. One of them eventually told a friend, and the friend told a teacher so it became a police case," he said, noting that the case took nine years to be prosecuted.

Boys are becoming victims as well. Dr Abdul Rahman Abdul Badayai, a developmental psychologist who volunteers at two children's shelters twice a week, said he sees an average of 12 cases a year involving boys who are sexually abused.

"When it comes to male victims, a lot of cases go unreported, probably because of culture," he said.

ACP Kamsiah said 20 per cent of child sexual abuse victims are boys, although she highlighted that this percentage share is increasing too.

In one case that Dr Rahman handled, the victim was exposed to indecent acts as a young boy. When his parents divorced and nobody could care for him, he was sent to a shelter.

But in the shelter, things took a turn for the worse. When he was 12, he was sexually abused by an older resident, aged 17. Two years later, he turned into a perpetrator and abused other boys instead.

It is a vicious cycle that starts when children lack parenting care at home, and when they are abused, they suffer emotionally and become psychologically imbalanced, often experiencing low confidence and trust issues, Dr Rahman said.

"What I'm afraid of is actually the survivors becoming perpetrators ... because they say they like it - they've been a victim for years and now they are the perpetrators," said Dr Rahman, who also heads the psychology and consultation clinic at the National University of Malaysia.

"When they start off this behaviour, they are sort of addicted to it. And then their self-esteem and self-control are very low, that's why they kind of repeat the behaviour."

When it comes to child sexual abuse material cases, perpetrators who are family members will usually coerce the victim into being recorded performing an indecent act, as they know that the victim is too scared to speak out, ACP Kamsiah said.

"There are cases where even the mother is too scared to report it, as male perpetrator is more dominant in the family," she said.

"This is why victims who are family members usually suffer for a long time, until they are able to get out or report it to friends or a third party."

Other perpetrators who are known to victims are usually in some sort of a romantic relationship. This is when a girl is asked to perform indecent acts on camera, and might not even know that they are becoming a victim of child pornography.

"The latest trend I see is that boys like to record these acts as a kind of keepsake," ACP Kamsiah said.

Perpetrators who are not known to victims usually start off by using a fake account or identity to get in touch with their victims on private messaging apps.

"The perpetrators usually befriend the victims and convince them to be lovers. Then they start to engage in explicit conversations, until the victim is influenced to share things like nude pictures," ACP Kamsiah said.

"This is when the perpetrator takes the opportunity to record or download these images, which will then be used to threaten and trap the victim into eventually having sex."

In some cases, the videos and images are shared with friends on various platforms, or if paedophilic elements are involved, in private groups or on the dark web.

ACP Kamsiah said these child sexual abuse material cases often escalate to physical sexual abuse, pointing out that they usually start with the sharing of explicit images, and culminate in having sex with a minor.

"They start with sharing nude images, then they meet and engage in sexual intercourse. So when a report is made, the police will classify it as a case of rape," she said.

CHALLENGES: STIGMA, MANPOWER SHORTAGE

Dr Rahman believes it is important that child survivors of sexual abuse be given not only physical shelter, but also sustained emotional support. He said some privately-run shelters lack intervention and counselling resources.

"They don't even have counsellors, and they are banking on volunteers to chip in," he said, adding that he helps monitor 30 private shelter homes registered in Selangor.

"If let's say the kids do not receive any proper and continuous intervention, throughout the years (the trauma) will be triggered again."

Dr Nayagam, who has four decades of experience handling child abuse cases, said suspected cases are first sent to hospitals to get a physical check-up. If the doctors confirm the abuse, the cases could be reported to authorities.

During case discussions with other agencies, he said he tries as far as possible not to place children in shelters, citing the "stigma" that comes with it.

Children need to be emotionally stable in the company of a family member, like a grandparent or cousin, he said.

Child survivors are placed in a shelter as a last resort. They usually stay for about six months, and move out when a caregiver can take them in, or when they are nearing 18 and ready to live and work independently.

Nevertheless, Dr Nayagam feels there is a lack of manpower in the child social service ecosystem, in terms of social workers, counsellors and psychologists.

"But we are moving in the right direction," he said.

On the investigation front, ACP Kamsiah said the new police team tackling child pornography - called Malaysia Internet Crimes Against Children (MICAC) - was set up in 2022 to analyse information, gather intelligence and conduct arrests in such cases.

However, she said MICAC currently only has 69 officers for the whole of Malaysia. Thirty-one of them are based at the Bukit Aman headquarters in Kuala Lumpur, leaving only "one or two" officers to be based in each of the country's 13 states.

ACP Kamsiah stressed that this is not enough considering that the police are handling an increasing amount of sex crime cases.

For instance, the police get tens of thousands of IP address reports each year from sources like Interpol, the US-based National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, as well as foreign law enforcement agencies.

These reports come with the child sexual abuse material that has been shared, and - in light of logistical constraints - officers must do an initial analysis of these images and videos and decide which are the most severe to be pursued.

"This material ranges from images of babies to older children, and I cannot deny that officers are affected emotionally," ACP Kamsiah said.

"We feel disgusted and angry with the perpetrators and sympathise with the victims. Some of us don't even want to look at it. But we put professionalism at the forefront of our work, and we take steps to heal and consult psychologists."

The identified material is then downloaded - keeping in mind the capacity and bandwidth of police servers - and further investigations are conducted.

Officers must confirm that the material indeed constitutes an offence, before reaching out to internet service providers and telcos to get the details of an IP address owner.

It is a time-consuming process, and it is only at this point that officers can move in for the arrest. Even then, the suspect might have already deleted the incriminating material, in which case they will get an advisory, ACP Kamsiah said.

"So from the thousands of reports we get, we narrow it down to a small number that we are capable of investigating, based on the expertise, logistics and manpower availability that we have," she said.

To highlight the challenges police face, out of the 27,051 IP addresses reported to the police so far in 2023, only 44 were investigated and 15 - or less than 1 per cent - ended in arrests.

Under the law, those who commit sexual crimes against children could be jailed for up to 20 years and caned.

If the accused persons were in a "relationship of trust" with the child, they could also be imprisoned for up to five years and be given a minimum of two strokes of the cane, in addition to the original punishment.

Those found making, possessing and distributing child sexual abuse material could be jailed for up to 30 years and given six strokes of the cane, as well as be fined up to RM5,000 (US$1,066), if found withholding information on sexual crimes against children.

As for the prosecution rate of child sex crime cases, of the 1,240 cases opened in 2022, 579 - or about 32 per cent - were charged. Others are still being investigated or have been closed or shelved with no further action taken.

"Some cases are straightforward, but the latest trend shows that some victims don't even know who the suspect is or where they live," ACP Kamsiah said, noting that in such cases, the suspects use a fake name and ask victims to meet at a certain location before moving elsewhere.

"The offence then takes place in a forested area or beside a sewer, so how will the police identify the suspect? It is cases like these that make it difficult for us," she said.

During investigations into child sexual abuse material, ACP Kamsiah said officers must also have the technical expertise to crack encrypted devices and navigate the dark web.

Some officers also try to infiltrate private groups related to such material, and thus must know how to evade detection by members constantly trying to sniff out moles by monitoring what others talk about.

ACP Kamsiah said the police will continue to improve technical training for officers, work with other agencies and request for additional manpower to better tackle sex crimes.

"We will continue to do our maximum," she said.

SOLUTIONS: BETTER COORDINATION, EMPATHY

For the overall situation to improve, Dr Rahman suggested that parties involved in child welfare - including the police, government agencies, schools as well as non-governmental organisations (NGO) - better work together and coordinate their resources.

"And maybe to create a system for the community to do safe reporting," he said, indicating that his research has shown that some people are afraid of reporting suspected sexual abuse for fear of repercussions, especially if the suspect is well-known in the community.

"I think the community is more crucial to me, to educate family members and the community on sexual abuse of children and how it impairs their development."

Dr Nayagam agreed, saying that the answer is not tougher laws but to help the less fortunate set up their own resident support committees in their neighbourhoods, in charge of looking out for each other, solving problems and distributing resources.

An NGO he works with has piloted this initiative with about 5,000 households at a low-cost government housing project called Desa Mentari in Petaling Jaya, saying that it has led to a decrease in cases of child abuse.

"What I did was empower the community to take care of themselves ... (and) bring their standard of living to a higher level," he said.

"We also identify from the residents any para-counsellors who can go to each house and visit them to find out what is the issue."

Ultimately, Dr Rahman encouraged adults to be more receptive and empathetic when handling children who might have experienced sexual abuse.

"Attitude is very important among adults dealing with this particular behaviour," he said.