‘Crossed the line’: Indonesia health minister’s controversial plans and comments spark calls for removal

Budi Gunadi Sadikin has come under recent fire for contentious remarks, such as higher earners being “healthier and smarter”. But despite mixed reactions to his policies and lack of medical experience, President Prabowo Subianto could keep him on, say experts.

Indonesia's Health Minister Budi Gunadi Sadikin speaks during an interview with Reuters at his office in Jakarta, Indonesia on Feb 6, 2025. (Photo: Reuters/Ajeng Dinar Ulfiana)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

JAKARTA: From making moves that would allow general practitioners to perform risky birth surgery, to controversial statements saying men with larger jeans sizes will “meet God sooner”, Indonesia’s health minister has come under heavy public criticism lately.

Some have even called for his resignation. As of Wednesday (May 21) evening, an online petition calling for Budi Gunadi Sadikin to be removed from office has been signed 8,600 times since it started on May 4.

“Throughout his tenure, the health minister has issued numerous policies and statements which are not pro-people, not based on scientific data and tarnish the credibility of health professionals,” the petition wrote.

The health minister’s policies and offhand remarks also led to a fierce debate over whether Indonesia’s top health post should be reserved for professionals with a medical background.

Over the last few days, lecturers from three of Indonesia’s biggest public universities: Jakarta’s University of Indonesia, West Java’s Padjadjaran University and East Java’s Airlangga University wrote open letters to President Prabowo Subianto, asking him to review Budi’s performance and policies.

The Alumni Association of University of Indonesia’s Faculty of Medicine joined the chorus of condemnation on Tuesday.

“(The association) encourages President Prabowo to replace the top health official,” Wawan Mulyawan, a neurosurgeon and association chairman, told reporters, as quoted by local media platform Tempo, adding that some of Budi’s policies and statements “have crossed the line”.

Analysts say the level of distrust shown by medical professionals and academics towards the minister is worrying as it affects how government policies are implemented on the ground.

“If this distrust drags on, the quality of health services people receive will be at risk,” Dicky Budiman, a public health expert from Jakarta’s Yarsi University, told CNA.

Budi was appointed health minister under the previous Joko Widodo government in 2020 and reappointed by Prabowo after he came to power in October.

A former banker with a degree in nuclear physics, Budi is the only second health minister in Indonesia who is neither a doctor nor a public health expert.

The first was Mananti Sitompul, a civil engineer, who held the position temporarily for a few months between December 1948 and March 1949 when the country was still at war with its former coloniser, the Netherlands.

Budi’s business background was an asset during the turbulence of the pandemic, said some experts. However, they stressed the importance of sector experience in a post-COVID world.

“During the (COVID-19) pandemic, (Budi) was the right man for the job because (Indonesia) needed someone who could make quick decisions and had good managerial skills,” Dicky said, adding that Budi’s experience in the corporate world gave him valuable expertise.

“(But) it is time for the health minister position to return to people who know the (health) sector well.”

However, some analysts feel that removing Budi from office and reserving the health minister position for doctors and public health experts is excessive.

“(Budi) is not the only Cabinet member who has aired controversial statements. He is not even the first health minister in Indonesia who made controversial statements and policies,” said Windhu Purnomo, a public health expert from Airlangga University.

“In many other countries, the health minister position is not only for people with medical backgrounds because what matters is their strategic thinking and managerial skills.”

CONTROVERSIAL PLANS, STATEMENTS

Criticism towards Budi intensified this month after the minister issued one controversial remark after another.

On May 14, Budi revealed during a parliamentary hearing that his ministry was formulating a regulation which would allow general practitioners in remote regions to perform caesarean sections to combat the shortage of obstetricians and gynaecologists in rural areas.

The ministry’s plan immediately drew pushback from the Indonesian Doctors Association and the Indonesian Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Association, both of which highlighted that such a procedure is "complicated and risky" and should not be performed by doctors without specialised training.

Also on May 14, Budi remarked that men with a jeans size of 33 inches or more are “definitely obese” and “more likely to meet God sooner” while he was attending the launch of a new health initiative to help the elderly population of Jakarta.

Three days later, on May 17, Budi made the news again, this time for saying at a discussion forum about the Health Vision Era of Prabowo in Jakarta that those with a salary of 15 million rupiah (US$914) per month “are definitely healthier and smarter” than those earning 5 million rupiah monthly.

The health minister is no stranger to controversy. Budi began attracting negative attention in May last year when he announced plans to allow foreign doctors to practise in Indonesia to combat a shortage of physicians in the country, particularly specialists.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Indonesia has 0.72 doctors per 1,000 people, which is below the organisation’s standards of one doctor for 1,000 people.

Doctors and health experts criticised the move, saying that the plan will only mean more competition for local doctors and does not address the problem of limited access to healthcare in remote areas, as foreign doctors are unlikely to be willing to be stationed in underdeveloped regions.

Budi was criticised by the health community again for saying the “stethoscope is very unscientific” during a discussion organised by Google in June 2024 and in an October webinar saying: “My predecessors (are) medical doctors. So they train (for) 10 years, 20 years to cure sick people, not to keep people healthy.”

Even when then-President Joko Widodo first named Budi as Indonesia’s health minister on Dec 20, 2020, reactions were mixed because of his non-medical background. Budi was replacing army physician Terawan Agus Putranto, who was lambasted by many health experts for his slow and complacent handling of the pandemic.

But Budi, who prior to being Indonesia’s top health official was vice minister for state-owned enterprises, soon proved his worth: Making sure hospitals across the vast archipelago were equipped to treat the influx of COVID-19 patients and securing enough vaccines to inoculate some 200 million Indonesians.

Budi’s handling of the pandemic was one of the reasons why Widodo’s successor Prabowo reinstated him as health minister.

“In the beginning, (Budi) realised that he had little knowledge about the medical world, but he was willing to learn and listen to more qualified colleagues and stakeholders,” Windhu of Airlangga University said.

“But after years of becoming a minister, he has since become overly confident in his knowledge of the health sector and started issuing statements and policies which drew the ire of medical professionals.”

CREDIBILITY QUESTIONED

After his statements on jeans sizes were widely lambasted on social media, the minister tried to defend his remarks, saying that he was simply choosing terms and analogies which were easy to grasp by ordinary people.

“I’m simply interpreting a health tip in a way people can understand,” Budi said as quoted by the Jakarta Globe.

But experts said Budi should not be oversimplifying things to the point that they start to defy medical and scientific conventions.

“Even school students know that you cannot measure obesity based on the size of someone’s jeans or gauge a person’s health based on one’s salary. It is understandable that there are many people, not just those in the health sector, (who) are upset (by the statements),” public health expert Dicky said.

“(The remarks) will greatly impact the credibility of the minister and the government in the eyes of ordinary citizens.”

Politician Yahya Zaini of the parliament’s health and social affairs commission said the minister must choose his words carefully to avoid confusion and controversy.

“All public statements should be supported by solid data,” the health commission’s deputy speaker said on May 18, as quoted by DetikNews.

Even though calls for Budi to be ousted have been intensifying, Prabowo may keep him on, say some experts.

“Before (Budi), there have been several members of Prabowo’s Cabinet who garnered widespread condemnation for what they said or did,” political analyst Hendri Satrio of Jakarta’s Paramadina University told CNA.

Among Prabowo’s ministers who once faced mounting calls to be replaced was energy and mineral resources minister Bahlil Lahadalia, who on Feb 1 decreed that subsidised cooking gas, which was originally sold at small stalls and convenience stores, should only be sold at “authorised distributors”.

The move resulted in a public backlash after residents were forced to travel far and wait for hours to acquire the subsidised cooking gas. Less than one week later, Prabowo intervened and repealed the regulation.

Another was Yandri Susanto, the minister of villages and development of disadvantaged regions, who was alleged to have used his position and influence to swing votes in favour of his wife Ratu Rachmatu Zakiyah, who was running in the November regional election in Serang regency, just west of Jakarta.

Ratu was on May 9 declared the winner of the Serang election but not before the Constitutional Court on Feb 25 ruled that Yandri had indeed intervened in the election process and ordered a revote in some polling stations.

“(These ministers) were reprimanded but still got to keep their jobs. I think the same will happen to the health minister,” Hendri said.

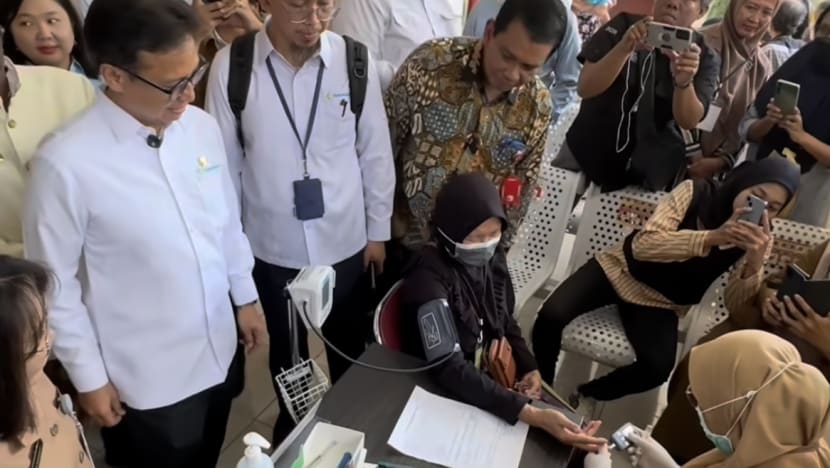

The political analyst said despite the controversies, Budi has shown Prabowo that he can deliver some of the president’s goals and campaign promises such as the free health check initiative which was rolled out in February and the upgrading of thousands of healthcare facilities in remote areas.

But even if he manages to keep his job, Budi would still need to work hard to regain the trust of medical workers and ordinary citizens, public health expert Windhu said.

“Going forward, he should focus on what he does best, worry about strategic and managerial matters and leave the technical, medical matters to his vice minister (Dante Saksono) and directors who do have backgrounds in health,” he said.

“(Budi) must focus on getting work done and showing results. That is the only way to regain the trust and support of the general public and health professionals because without their support, no government policy can be implemented successfully.”