India’s many languages pose a challenge to the development of its large language model

India currently has 22 officially recognised languages and more than 10,000 local languages, making it complicated to code an AI model that can process all these languages seamlessly.

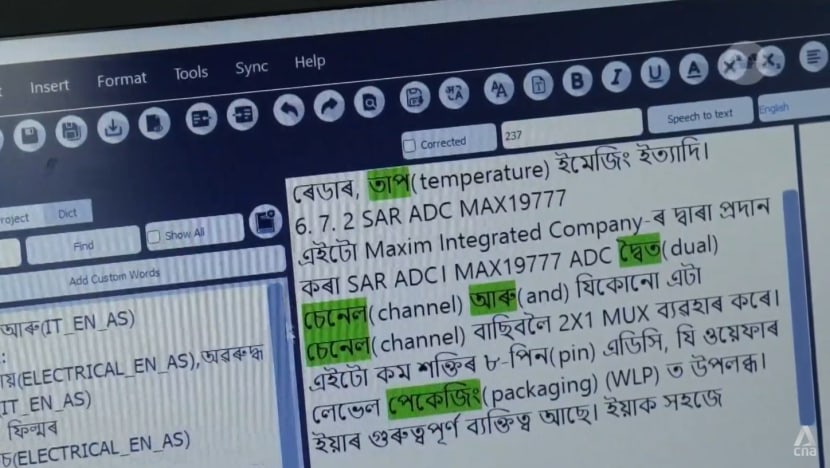

Employees work with languages at BharatGen, a language-based AI project, in India.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

NEW DELHI: India is building its own large language model it hopes one day may rival OpenAI's chatbot ChatGPT, but the country’s countless languages and dialects have made training it a challenge.

India has 22 officially recognised languages and more than 10,000 local languages.

Some languages like Marathi share common roots with others such as Hindi and Gujarati, while others spoken in South India - such as Kannada, Telugu, Tamil and Malayalam - are completely different.

A large language model has to process these multiple languages seamlessly, and coding an AI model capable of understanding most of them, if not all, remains complicated.

TRAINING AI ON LOCAL LANGUAGES

One challenge faced by BharatGen, a consortium funded by India’s government, in training their large language model is a lack of online content in Indian languages.

The consortium said that while roughly half of all the data available on the internet is in English, Indian languages make up barely 1 per cent.

Literary works in many Indian languages have never been digitised, while a raft of cultural and traditional information has been verbally passed down for generations without being stored online.

On a more positive note, experts said that the diversity of languages and data collected from local sources could help create AI models with fewer biases.

Ganesh Ramakrishnan, a professor at the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, told CNA his work involved reaching out to magazines, data sources, foundations and non-governmental organisations who have been gathering data in their local languages.

“(We have been) making it possible to digitise and digitalise and reflect that in the foundational model … so this is a big opportunity,” said Ramakrishnan, who is part of the BharatGen consortium.

EXISTING CHATBOTS ARE INADEQUATE

Some small business owners, who have tried using AI as part of their operations, said they have faced language challenges when using existing chatbots.

Ghooran Yadav, a food cart owner in New Delhi, said that he used ChatGPT to enquire about the recipe of the food he sells, but received an underwhelming response.

The app understood his question in the local dialect of Bhojpuri but replied in Hindi.

Ghooran said foreign chatbots are not as accurate and that he prefers a locally-made app.

“If it’s made in India, it’s more likely to give me correct information. Nothing could be better than that,” he added.

EASE OF USE

BharatGen is also aiming to utilise generative AI to solve everyday problems and eventually help deliver services such as providing information about welfare programmes to the people.

An app called Krishi Saathi (“With Farmers” in Hindi), which is powered by BharatGen’s Hindi language model, is helping to answer farmers’ questions about crop health and pest management.

The app can translate text to local languages. It also allows those who are unable to read or write to communicate by speaking via the app.

“Making sure that the most remotely inaccessible regions also benefit from AI - that is part of the vision here,” said Ramakrishnan.

The AI model can copy a speaker's voice and tone, communicating with the user like an actual person once it has been trained to do so.

BharatGen, one of five major language-based AI projects currently supported by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi's government, has already rolled out 19 language models since its inception last year.

Experts said platforms like BharatGen need to invest billions of dollars on graphics processing units and data centres to achieve made-in-India generative AI at scale.

The hefty price tag would be a small price to pay to transform India from a major tech service provider to a major tech disruptor, in what could soon be a trillion-dollar market.

“India is all about scale and complexity,” said Shekar Sivasubramanian, head of the LEHS-AI unit at non-profit AI institute Wadhwani AI.

“If it is solved in India, and if it works in India, chances are, it will work in the world. That’s the opportunity.”