To the moon, Mars and beyond: Could China’s soaring space ambitions be hampered by earthly factors?

While the potential gain is clear, the question is whether Beijing will keep the funds and focus flowing as earthly considerations loom large.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: “To explore the vast cosmos, develop the space industry and build China into a space power is our eternal dream.”

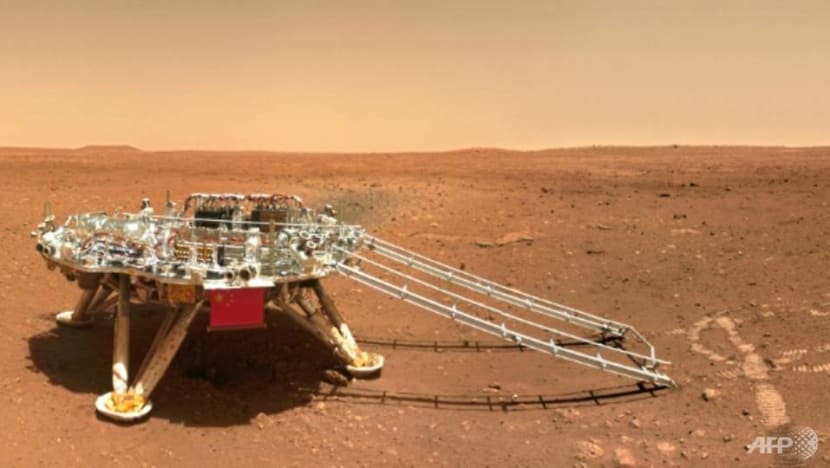

These words by Chinese President Xi Jinping opened the country’s latest space white paper published in early 2022. At the time, Beijing was flush from its extraterrestrial achievements, such as a world-first landing on the dark side of the moon in 2019 and a historic first for the country in its touchdown on Mars in 2021.

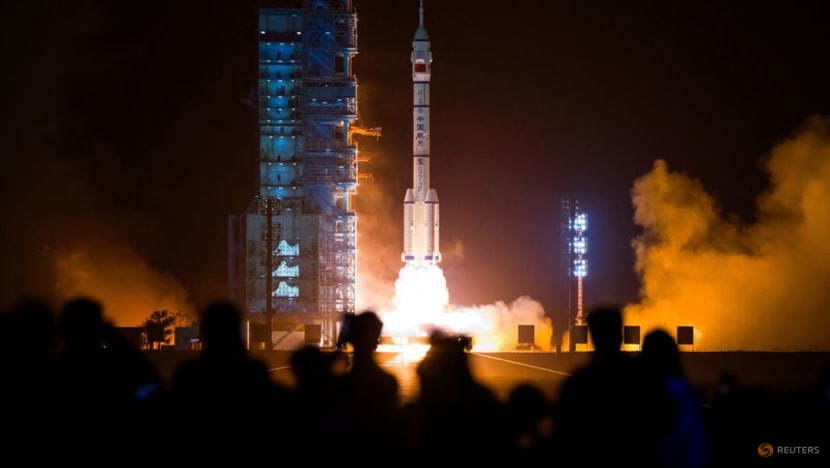

Fast forward to now and Beijing is keeping its space ambitions fired up, blasting off towards a record launch year while charting further lunar and deep space explorations over the next decade.

The latest exploit was on Apr 25, when three Chinese astronauts embarked on China’s latest crewed mission to its homegrown space station. Barely a week before that, the Chinese military elevated the status of its space unit as part of a wider defence reorganisation.

From political prestige to scientific advancements - observers say the potential gain is clear as China reaches for the stars through its space ambitions. The rub is whether the world’s second-largest economy will keep the funds and focus flowing towards its ventures beyond Earth as domestic and external challenges loom ever larger.

“Slower overall economic growth in China may impact the government's willingness to spend on space,” Mr Clayton Swope, deputy director of the Aerospace Security Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), told CNA.

Against this backdrop, analysts interviewed by CNA suggest that serious expansion of the commercial space arena could be key in easing pressure on Chinese government coffers by tapping private enterprise to supplement state endeavours while still advancing innovation and development.

At the same time, China has to consider how its earthly international relations could impact its ambitions beyond the atmosphere, especially with vocal callouts by American officials over security, spying and space territorial concerns.

“We should expect national activities in space to reflect geopolitical tensions on Earth,” said Mr Swope.

ROCKETING TOWARDS NEW HEIGHTS

China joined the space age many moons ago in 1970 with its first successful satellite launch. While its space programme has been grounded in progress ever since, data points to a meteoric rise in recent years.

One indicator is the number of orbital take-offs. According to a CSIS China Power report, China conducted 207 launches between 2010 and 2019, more than one-and-a-half times its count in the previous four decades.

The tally has only risen since then. China logged 225 space launches from 2020 to 2023. This year alone, the target set is “about 100” - a record high - as announced in end-February by the state-owned China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC), the country’s leading space contractor.

This places China in second place globally - behind the US’ 269 launches from 2020 to 2023, but firmly in front of third-ranked Russia, which logged 68 take-offs across that same period.

China has been making history in space landings as well. Its Chang’e 4 craft landed on the dark side of the moon in 2019, a world first. In May 2021, the Chinese rover Zhurong successfully touched down on Mars to make China the second nation after the United States to achieve this feat.

Beijing has also established a permanent outpost in Earth’s orbit. The Tiangong Space Station has been fully operational since late 2022 and is scheduled to outlive the older, larger International Space Station (ISS).

Such achievements are a clear reflection of China’s space prowess, observers note.

“It is clear to me that China has already emerged as a major space power, not just in terms of launches per year … but also in terms of the significance of the missions and portfolio of major accomplishments,” Professor Quentin Parker, director of Hong Kong University’s (HKU) Laboratory for Space Research, told CNA.

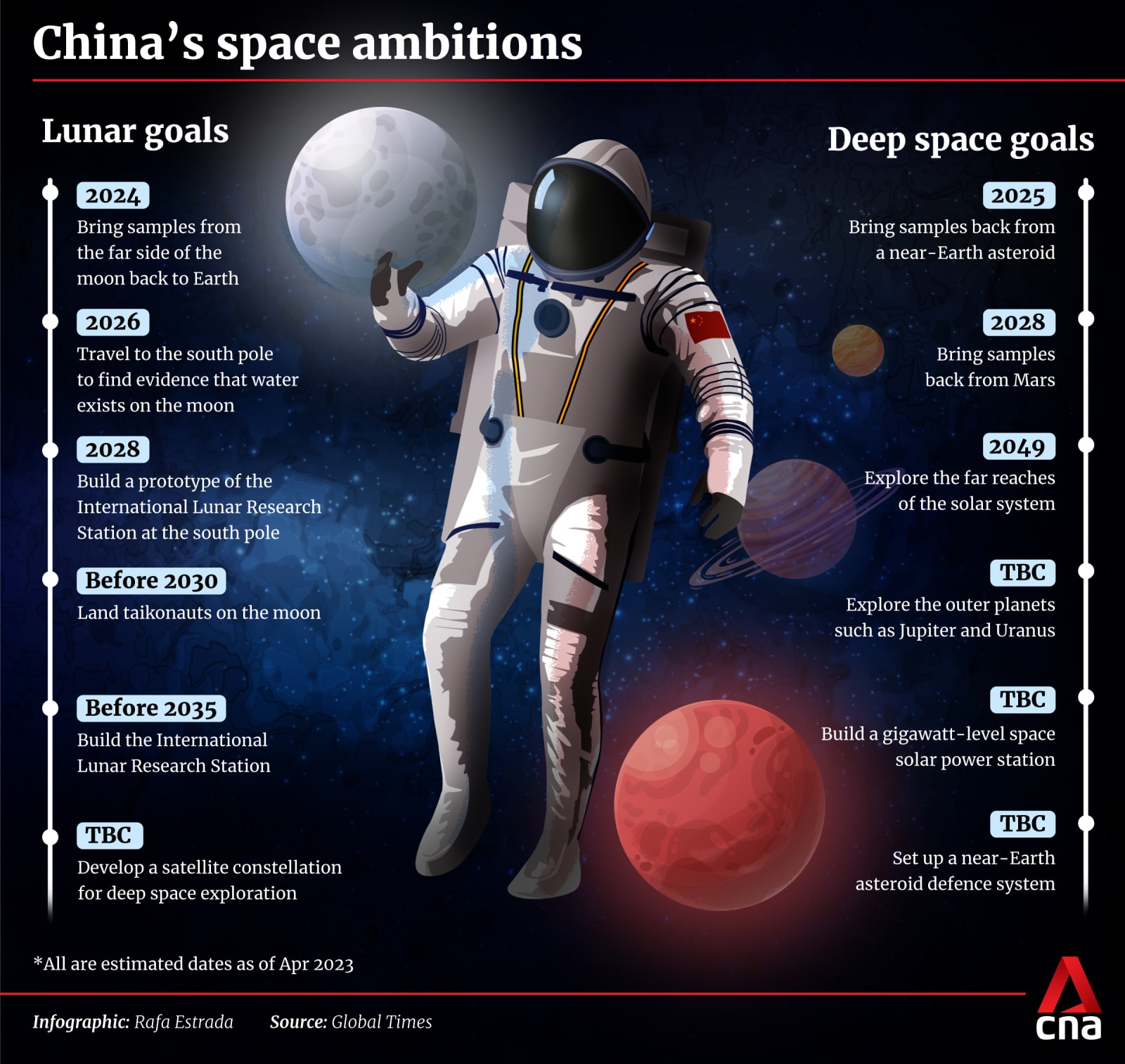

And Beijing has more space missions on its radar. Among them is an inaugural expedition to retrieve lunar samples from the far side of the moon, planned for take-off in the first half of the year. It is also planning a manned mission to the lunar surface by 2030.

Further afield, an unmanned exploratory sortie to the outer planets is slated for launch around 2030.

ENHANCING SECURITY THROUGH SPACE

Observers say China is acutely aware of the benefits space exploration brings, as seen in its national space programme goals.

Beijing states that one of its objectives is to “meet the demands of economic, scientific and technological development, national security and social progress”. Also, to raise the “scientific and cultural levels of the Chinese people, protect China's national rights and interests, and build up its overall strength”.

The benefits of space exploration are well documented, with the advances beyond the atmosphere also having spillover benefits on Earth.

In a recent example, America’s National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) demonstrated in June last year that it could achieve a 98 per cent water recovery rate on board the ISS, a key threshold for a possible self-sustaining system.

Meanwhile, a European Space Agency article cites examples of how water purification technology developed for the ISS has been adapted on the ground, making a “life-saving difference” to communities in at-risk areas.

China’s expanding presence in space has already borne fruit, as seen in its homegrown navigation system BeiDou’s growth in the global navigation satellite system arena dominated by America’s Global Positioning System or GPS.

Related:

Completed in 2020, the BeiDou system consists of nearly 60 satellites, dwarfing GPS’ 31-strong constellation.

In a nod to its capabilities, BeiDou was recognised as a global standard for commercial aviation late last year. A US government advisory board on GPS stated in January last year that “GPS’s capabilities are now substantially inferior to those of China’s BeiDou”.

The positioning and timing services of the BeiDou system were used more than 100 billion times a month as of March 2022, according to a report by the state-run People’s Daily. It’s also proving lucrative - a senior Chinese official said in 2021 that the value of industries related to the BeiDou system is estimated to exceed one trillion yuan (about US$156.4 billion) by 2025.

“(China) recognises that BeiDou’s commercial applications can enhance the CCP’s (Chinese Communist Party) political, economic and security goals,” reads a 2023 report by the US-based Belfer Center.

CSIS’ Mr Swope believes China is primarily focused on using space to achieve its national security objectives amid rising geopolitical tensions and a Sino-US tussle for global influence.

“Space (fits) squarely within its concept of informatised operations,” he said. “China has launched over 400 satellites over the last two years. Half of those are remote sensing satellites. These satellites enhance Beijing's ability to track forces and assets across the Indo-Pacific region.”

But China says its reconnaissance satellites are by and large for civilian and commercial purposes - assertions which the US disputes.

Beijing has made clear the value it places on information, especially for defence purposes. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) unveiled a new strategic branch dedicated to information operations on Apr 19 as part of its biggest defence shakeup in nine years.

China also uses its space programme to recruit diplomatic allies, Mr Swope noted, highlighting how Beijing is working with Russia to build a coalition supporting plans for its International Lunar Research Station and exploration of the moon’s surface.

China and Thailand signed space-related agreements in March. Last week, President Xi highlighted that China is ready to work with Latin American and Caribbean countries on closer space cooperation and technology.

THE BUSINESS OF SPACE

As China looks to reap further benefits through its expanding space exploits, analysts say a key question is whether Beijing will keep the funds flowing in the face of growing turbulence on Earth.

Observers note that China has the second-largest space budget in the world after the US, with spending doubling in recent years. “In 2022 alone, it spent an estimated US$16.1 billion on space,” said Ms Svetla Ben-Itzhak, an assistant professor of space and international relations at Johns Hopkins University's School of Advanced International Studies.

But the world’s second-largest economy is grappling with a host of issues including a protracted real estate slump, sluggish domestic spending and a shrinking workforce. Geopolitical tensions also weigh heavily as the West keeps up its de-risking strategies.

It remains to be seen as well whether China can translate national advances in space to sustained economic development, CSIS’ Mr Swope told CNA.

Against this backdrop, the commercial space arena could provide breathing room for government coffers while ensuring continued research and innovation, analysts say.

“One only has to look at what has been achieved in the United States … to see what impact commercial space ventures can have,” said Prof Parker.

“NASA is still a key player but it has outsourced much of the heavy lifting both literally and figuratively to private enterprise. These enterprises are less risk-averse and seem to be able to make more rapid progress,” he added, singling out SpaceX as a primary example.

Founded by billionaire Elon Musk in 2002, SpaceX has carved out an outsized presence in the US commercial space sector. It singlehandedly ensured the US remained in the lead for orbital launches last year - accounting for 98 of the 109 attempts made by Washington.

SpaceX is also integral to the US government’s space programme - flying crew and cargo to the ISS, launching NASA science spacecraft and also flying payloads for the Department of Defense, according to American non-profit The Planetary Society.

The lay of the land is different in China’s space sector. The industry has long been dominated by state-owned enterprises, with CASC and the China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation the leading players.

While commercial participation has increasingly been allowed since 2014, the state still accounts for the lion’s share of the industry. Still, in recent times the country has been publicly beating the drum for the business of space.

China’s Central Economic Work Conference in December last year identified the commercial space industry as one of several strategic emerging industries to nurture. The government’s work report in March also singled out the sector as a priority.

According to statistics from the China Aerospace Industry Quality Association, the country's commercial aerospace market size increased from 376.4 billion yuan in 2015 to 1.02 trillion yuan in 2020.

“Could a Chinese equivalent of Elon Musk emerge?” pondered HKU’s Prof Parker.

GEOPOLITICAL TURBULENCE

As China’s space programme hits new heights, analysts say Beijing will have to contend with competition and concern as fellow major space powers sit up and take notice.

The US has been vocal about its uneasiness towards China. Early last year, NASA’s chief asserted that Washington and Beijing are locked in a space race. Mr Bill Nelson also warned in an interview with US news outlet Politico that China could try to dominate the most resource-rich locations on the moon.

“We better watch out that they don’t get to a place on the moon under the guise of scientific research. And it is not beyond the realm of possibility that they say, ‘Keep out, we’re here, this is our territory.’” he said.

More recently in April, Mr Nelson told lawmakers on Capitol Hill that he believes China is concealing military activity in space.

Beijing has refuted the allegations. A Global Times editorial published in January said any notion of a space race is “imagined by the Americans”, and China has no intention of participating in it.

“China's development of aerospace technology emphasises three aspects: peaceful utilisation, equal mutual benefit, and inclusive development,” the article stated.

HKU’s Prof Parker, when asked what poses an overriding threat to China’s space ambitions, indicated that deliberate containment policies from “powerful state actors” beyond the country are playing a negative role.

While he did not elaborate on their identities, Prof Parker believes such efforts will “ultimately be self-defeating”. He brought up a US law that bans NASA from cooperating with the Chinese government. Passed in 2011, the so-called Wolf Amendment has been renewed annually through new spending bills.

A notable consequence of the Wolf Amendment is the effective ban on China from the ISS. All this did in the end was to “turbocharge” China's space programme, said Prof Parker.

Still, as competition heats up, CSIS’ Mr Swope expects national activities in space to reflect the earthly state of play. Even so, he points out that a “big unanswered question” is how exactly nations will protect their space capabilities so they are available when national security is at stake.

Activities beyond Earth’s atmosphere are governed by the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which has been signed by all major spacefaring nations. It binds the parties to use outer space only for peaceful purposes while stating there is no claim for sovereignty in space.

Under the treaty, military bases and weapons testing are forbidden on all celestial bodies. Parties also undertake not to place weapons of mass destruction - including nuclear arms - in Earth’s orbit or on celestial bodies.

The protection of satellites is particularly on countries' radars considering how they’re “largely defenceless”, said Mr Swope. At the same time, they fulfil an array of critical functions - real-time communications, navigation and positioning, and weather prediction, to name some.

“Can (protection of space capabilities) be done using international agreed-to frameworks on norms for behaviours in space? That might work on most days, but probably not during a conflict,” he noted.

Ms Svetla from Johns Hopkins University pointed out that China is one of only four countries that have successfully demonstrated kinetic anti-satellite capabilities. India, Russia and the US make up the other nations.

At the end of the day, even as other countries make progress and space becomes more crowded or potentially even more dangerous, Ms Svetla believes China alone is the pivotal factor to whether its space ambitions flourish or stall.

“The future of today is no longer only about who gets to space or any celestial body first, but about who manages to survive and thrive in the harsh conditions of the space environment,” she told CNA.

“Long-term dedication, resources, and a close network of friends and allies may prove key to doing so sustainably and successfully.”