AI in Southeast Asia: As rules are drafted, workers share their worries and wishes

The race is on to regulate AI globally as concerns grow over the impact on jobs, safety and privacy. In the first of a regular series examining AI's development in Southeast Asia, CNA looks at how regulations will shape domestic policies and harness the evolving technology.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

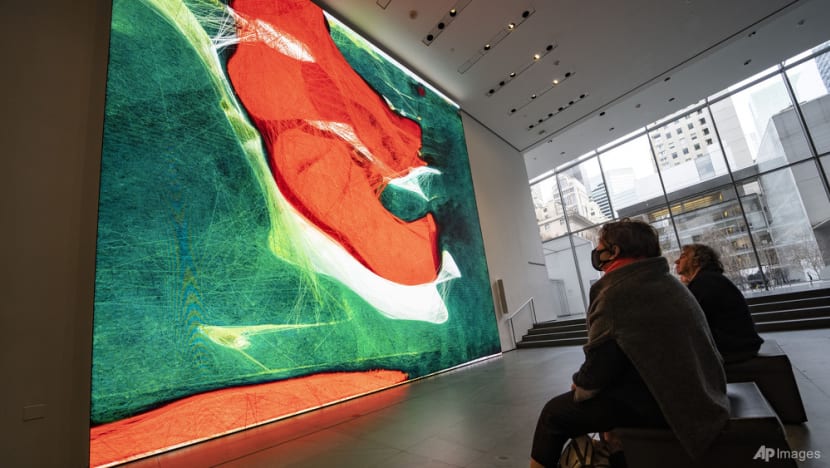

SINGAPORE: Freelance animator and illustrator Denise Yap, 28, accepts that artificial intelligence (AI) is pushing the boundaries of her artistic profession in more ways than one.

“The amount of cool concepts and ideas I’ve seen built out of AI have been rather intriguing, to say the least,” the Singaporean told CNA.

ChatGPT was launched exactly a year ago, taking the world by storm and thrusting generative AI into the limelight.

Since then, generative AI art tools like DreamUp, Midjourney and Stable Diffusion have seen a boom in popularity. These tools allow digital artists to produce novel works - some in a matter of seconds.

The AI uses machine learning to analyse thousands of images online, factoring in the user’s instructions and aesthetics.

For Ms Yap, therein lies the issue.

“In an ideal world, when AI is building data sets on living artists, they would by right have to consent before (their images) are added in,” she said, calling for laws that better protect rights holders like her.

“AI art is really early in its conception, and thanks to that there’s a lack of boundaries being set.”

The debate over copyright has been seen around the world, with some artists angered by AI copying the styles they have sacrificed years to develop, often without consent or compensation. This has sparked questions of intellectual property ownership and legal challenges in countries like the US.

But this is only one of the ground-up fears that AI has brought on. Some are worried about losing their jobs, while others say the technology could be used for nefarious purposes.

AI systems used in recruitment and judicial processes also risk perpetuating biases, as the training data they use could be encoded with socio-economic, racial, religious and gender prejudices, experts say.

At the same time, the potential of using AI to do good is also there - from driving automation to predicting illness.

Against this backdrop, a race for AI regulation is taking place to avert the risks while hopefully reaping the rewards - with action being taken at the global, regional and national levels.

An international milestone was logged just a month ago. The first-ever AI Safety Summit, held in the UK on Nov 1, saw the US and China coming together with more than 25 other countries to affirm the safe and responsible use of AI.

The landmark agreement also places “strong responsibility” on developers of frontier AI to test their systems for safety.

Frontier AI often refers to the first wave of mainstream AI applications like ChatGPT.

On a regional scale, the European Union is in the final stages of formulating its AI Act, a far-reaching law that would classify AI systems by risk and mandate various development and use requirements.

Closer to home, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is planning to draw up governance and ethics guidelines for AI, which analysts told CNA are expected to suggest “safeguards” that can mitigate identified risks.

While the guide is not expected to translate into regional legislation, it could spur individual member states to create new laws or tweak existing ones to regulate the technology, they added.

Countries behind the AI curve will also get a leg up as they can benefit from the sharing of knowledge.

“The public should care about AI regulation because the technology is more pervasive than we normally think,” said Dr Karryl Sagun-Trajano, a research fellow for future issues and technology at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), pointing out that AI is used in sectors like healthcare, education, transport and crime fighting.

IS AI COMING FOR YOUR JOB?

The potential for AI to upend the labour market and disrupt industries has been much discussed. A Goldman Sachs report predicts that as many as 300 million jobs could be impacted by AI automation.

Observers have warned that faster, smarter and cheaper AI-powered chatbots could replace outsourced call centres handling customer service for many companies.

This is especially stark for countries like India and the Philippines, where call centres provide modest-paying work and surveys have shown automation could render over a million jobs obsolete.

There are similar concerns in Thailand too.

The Bangkok Post reported in 2018 that 72 per cent, or almost three-quarters, of Thai graduates could lose their jobs to AI by 2030. Most at danger are administrative and office workers who lack all but routine skills, Thailand’s deputy education minister said.

Thai national Kulvadee Pounglaph uses Google’s AI chatbot Bard in her job to draft speeches for her manager.

“It saves a lot of time because when you work with languages, you have to think a lot. But with AI, it’ll provide an example. We can read it and edit it a little,” the 36-year-old told CNA.

At the same time, Ms Pounglaph, who works in procurement, acknowledged the risk that AI bots such as Bard - which she said talks “like a human” - could take over jobs like hers.

“AI may affect people who work with languages; they could be dismissed. Still, AI doesn’t know everything. It does have a database but when it comes to creativity, not so much,” she said.

Ms Pounglaph hopes that Thailand can introduce laws stipulating a quota for human employees in bigger companies, after considering the number of jobs that AI could replace.

Besides paving the way for the enforcement of an AI law and regulation, a key prong of Thailand’s National AI Strategy and Action Plan - launched last year - is to improve AI-related education and manpower capabilities.

In a progress report in August, the government said it had endorsed a plan to develop an AI-skilled workforce to support the industrial sector’s diverse needs.

ASEAN GUIDELINES COULD SPUR LOCAL LAWS

This is where an ASEAN AI playbook could come in handy, experts say, by providing overall guidance for countries to reference and tweak where needed.

The bloc is working on an AI governance and ethics guide, with Reuters reporting it could be announced at the 4th ASEAN Digital Ministers’ Meeting in early 2024 when Singapore is chair.

Earlier this year, the regional bloc agreed on the need to establish policies and regulations to spur the development of AI towards an “innovative, responsible and secure ecosystem”.

Singapore’s Ministry of Communications and Information told CNA the guide will serve as a “practical and implementable step” towards this end.

Ms Kristina Fong, who researches ASEAN economic affairs at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, said the guidelines are not expected to translate into legislation on a regional bloc level as ASEAN is an intergovernmental organisation with no parliament and thus no legislative power.

She pointed out that the main benefit of the joint effort would be “the initiation of a coordinated dialogue (on AI), to assess risk and ensure that the region is prepared to respond to adverse incidents”.

“Considering the most pressing needs for safeguards in this space, the main regulatory building blocks fundamental to protect users from harm would be personal data protection, cybersecurity, consumer and producer protection and copyright legislation,” Ms Fong said.

Dr Sagun-Trajano from RSIS said a coordinated regional effort will allow countries that are more advanced in specific areas, like technological development, to help those still playing catch up.

“The ASEAN model, if done right, may be a good model for other countries, not as a one-to-one example, but as an effort to moderate guardrails based on the region’s contextual factors,” she said, referring to areas like the region’s political, economic, social, technological, environmental and legal landscape.

DIFFERING LEVELS OF AI DEVELOPMENT

Countries in the region should ensure they have adequate AI regulatory frameworks before a well-functioning regional policy can be implemented, Ms Fong told CNA.

Out of the 10 ASEAN member states, four - Brunei, Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar - have not developed their own AI strategies, Ms Fong noted in a commentary published by the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.

Common themes observed in the other six countries’ strategies include using the technology for economic growth and development and establishing ethical and governance frameworks for AI applications.

In addition, Singapore and Malaysia have a “strategy of leverage through international bodies or frameworks”, Ms Fong wrote in her commentary. For instance, Singapore’s seat on the European Commission’s High Level Expert Group on AI allows it to influence global standards.

Also of interest is Indonesia, which according to 2021 data by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development has the largest share of digital service imports among ASEAN countries.

Indonesian news agency Antara reported in August that Jakarta is preparing to launch AI-related ethical guidelines to protect personal data. It is expected to cover how AI models scrape datasets for training.

Civil servant Mr Irvan, who only wanted to be known by his first name, uses AI in his job to help with copy editing and data analysis, but fears that the tech could go beyond collecting personal data and learn human intuition.

“If it (steals) our ID number - that’s our personal data. But how we behave, it’s something that AI could understand,” said the 39-year-old civil servant, who is concerned that AI could achieve world dominance as portrayed in some movies.

“This is what I’m more afraid of. They know how humans will behave, how you might react because of a certain motive or background.”

Mr Irvan noted that AI could be used to create convincing deepfakes and fake news.

“If you can create a fake article and you don’t know whose agenda it is – is it the user or the AI – it can drive people’s will,” he said.

“If the regional bloc can give guidelines, probably this will push local governments to create regulations also.”

Still, he hopes countries in the earlier stages of AI development do not hold the rest back. “When it comes to regulations, country A and country B could have different agendas.”

BALANCING INNOVATION AND REGULATION

It is “very likely” that ASEAN will try to expedite its AI guidelines as the need for regulation gains pace, but the “key test” is whether they will be impactful in domestic policies, said Ms Fong from the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.

“Policy prescription for innovative industries is always very tricky. There is a risk of being too rigid and strict, stifling further innovation, but also running the risk of being too light-touch and putting society at risk,” she added.

“With the dynamic characteristics of AI, countries will need to think carefully about how to go about monitoring and supervising its development, if not through outright regulation.”

How should AI be regulated in Southeast Asia? CNA asks ChatGPT

We asked ChatGPT 3.5: "Explain in 100 words how AI should be regulated - specifically in Southeast Asia."

The generative AI tool took less than 10 seconds to produce an answer - this was its response:

"In Southeast Asia, AI regulation should strike a balance between fostering innovation and safeguarding ethical use. A comprehensive framework must address data privacy, algorithmic transparency, and accountability.

Collaborative efforts among regional governments are crucial to ensure consistency in standards, preventing potential loopholes.

Regulations should evolve with technological advancements, promoting adaptability while guarding against misuse. Public engagement and awareness campaigns are essential to demystify AI, fostering informed discussions.

Striking this equilibrium will empower Southeast Asia to harness the benefits of AI while mitigating risks, ensuring responsible development that aligns with regional values and promotes a fair and inclusive digital future."

Mr Josh Lee, Asia-Pacific managing director of the Future of Privacy Forum, said countries could opt for soft regulation, such as voluntary and non-binding industry codes, guidance, standards, licensing requirements, and certifications.

They could also go for hard regulation in the form of rules and laws, he said, although this could create uncertainty and concern among AI players in the country.

“There will be questions about how key terms are defined, the scope of the regulation, how the relevant regulator will interpret the regulation, and how the regulation may intersect with existing laws,” Mr Lee explained.

For instance, requesting companies to sieve through all of their AI training data to minimise all forms of bias would use up a lot of time and resources, impacting small- and medium-sized enterprises the hardest.

A requirement to submit details about an AI system to a regulator for assessment could also raise concerns about divulging confidential information and trade secrets that compromise a company’s profitability.

“Regulations that are poorly drafted could lead to companies planning to develop or deploy innovative AI products or services to shelve their plans, or simply pull out from the jurisdiction altogether,” said Mr Lee, who deals with the intersection of law, policy and technology.

CREATE NEW LAWS OR AMEND EXISTING ONES?

Mr Lee said the “million-dollar question” is whether there needs to be technology-specific regulation for AI, or if it is sufficient to tweak broad rules that already cover different aspects of the development and the use of AI.

This, he said, should depend on whether a jurisdiction can effectively enforce relevant regulations, and whether it considers that AI, from a technical perspective, poses novel challenges that existing regulations cannot address.

Ms Fong at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute highlighted that most countries have opted to look more closely into incorporating AI-related elements into existing legislation, as this is deemed the most efficient way of addressing inherent risks and implementing safeguards in a timely manner.

Amid developments in generative AI, Singapore in 2021 amended its Copyright Act to allow for the copying of copyrighted works for the purposes of both commercial and non-commercial data analysis.

This also includes safeguards to protect the interests of copyright holders. Users of this exception must have lawful access to the works that are being copied, and the works may not be distributed to those without lawful access.

Ms Pin-Ping Oh, a partner at the Singapore office of Bird & Bird, a law firm specialising in tech and innovation, told CNA the amendment means an AI art platform’s use of images as training data could be covered under the new exception, provided it meets the requirement for “lawful access”.

“The way forward appears to be to consider how a licensing model can be put in place to ensure that AI developers have access to the training data that they need, whilst also ensuring that creatives and other rights holders are fairly compensated for the use of their works,” she said.

At the end of the day, this is just one piece of the regulatory puzzle for Singapore and the rest of the world as they contend with other aspects of AI such as privacy, security and accountability.

“We need to make sure that AI will be a force that doesn’t just get better - it also needs to be used for good,” said Dr Sagun-Trajano from RSIS.

“Regulation, if done well, will bring us closer to that goal.”

Additional reporting by Pichayada Promchertchoo

Read this story in Bahasa Indonesia here.